According to the release, the 14 groups represent the “initial findings” of a task force that Macarro established after winning the NCAI presidency a year ago. At the 2023 annual convention, tribes debated — and eventually rejected — proposed amendments that would have limited membership to federally-recognized Indian nations and their citizens, leaving state-recognized groups out of the fold. But as the release indicates, the work of the Membership Integrity, Education, and Healing Task Force is far from over. The group, which consists of 10 leaders from across Indian Country, plus two co-chairs, is continuing to review how NCAI addresses issues of legitimacy that have arisen within the ranks. “We look forward to the task force’s continued work and our further shared goals of education and healing,” Macarro said in the release, which did not identify the groups whose memberships in NCAI are pending. NCAI’s commitment to integrity was in fact put to the test during the convention. A day prior, the organization issued an apology to the Lumbee Tribe, a state-recognized group based in North Carolina, over “inflammatory materials” that were distributed at the gathering in Las Vegas, Nevada. The October 29 statement did not describe the nature or content of the materials. But attendees said a flyer placed on tables and chairs at the convention contained a link to a tribally-developed website that opposes federal recognition for the Lumbees. “This is a violation of the code of conduct by which all members are bound,” NCAI said in the statement. “It is an unacceptable breach of the standards and spirit of community, consensus, and inclusion that NCAI works hard to promote and safeguard. We regret and apologize for the divisiveness this unethical action has caused.” “We also apologize to the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina for this insult,” read the statement, which included a copy of the code of conduct.“… Earlier this year, the NCAI Executive Committee established a task force of elected leaders from Tribal Nations throughout the United States in order to address membership integrity, education, and healing…” 📰

— National Congress of American Indians (@NCAI1944) October 31, 2024

Read the full statement: https://t.co/Y681DIVxws. pic.twitter.com/VaguAxCyBW

The United Indian Nations of Oklahoma, the inter-tribal organization that developed the flyer and website, and the Great Plains Tribal Chairmen’s Association hosted a session of their own in Las Vegas that focused on opposition to legislation in the U.S. Congress that would extend federal recognition to the Lumbees. The gathering took place on Tuesday morning, the day before the NCAI apology. The two controversies indicate that last year’s debate about the presence of state-level groups at NCAI is far from settled. The host of the organization’s mid-year convention in June, for example, was the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, whose leadership warned before and after the event of “fake groups” that claim to be Cherokee. “We also learned how much harder we are going to have to work to defeat fake groups identifying as Tribe and/or Tribal government,” Principal Chief Michell Hicks said at the conclusion of the convention at the Harrah’s Cherokee Casino Resort in North Carolina. A handful of groups claiming to be Cherokee in fact are among the initial 14 whose membership was not renewed in NCAI, according to an attendee of the Las Vegas conference. A number of these groups lack formal recognition by a state government and instead are merely chartered or incorporated under state law, which goes against the organization’s existing by-laws. “We’re not reinventing the wheel here. We’re executing previous policy that’s been voted on by the executive council,” NCAI President Macarro said when asked about the developments at a lengthy tribal caucus in Las Vegas, during which both the membership renewals and the Lumbee apology were discussed.NCAI condemns the unauthorized distribution of inflammatory materials at #NCAI81 today. This violates our code of conduct and the standards we uphold. We apologize to our attendees and to the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina for this great insult.

— National Congress of American Indians (@NCAI1944) October 29, 2024

🔗 https://t.co/IT2ZB7PBWg pic.twitter.com/ZGV9sucYac

But some tribal leaders were taken aback by the membership renewals issue. One representative of a Southeast Region tribe that gained federal recognition after being state-recognized said the issue has caused considerable controversy among his peers. “It’s not good for us, it’s not good for our caucus,” the tribal leader told Macarro. “It’s not good for NCAI.” Representatives from the Northeast Region also voiced concerns about the membership renewals and how it affects the larger debate about state recognition. Nearly every tribe from the region — notably those in Connecticut, Maine and Massachusetts — didn’t gain federal recognition until the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, but all had long been recognized by state governments, even going back to colonial times. One prominent leader from the Northeast told Indianz.Com that the ongoing debate has “equated state recognition with fake tribes.” “That’s despicable,” the person said. During the tribal caucus, which lasted about three hours, Geoffrey Blackwell, NCAI’s general counsel and chief of staff, said that the Membership Integrity, Education, and Healing Task Force has reviewed as many as 27 applicants. He indicated that the groups hail from “multiple regions” of the United States, after some at the meeting questioned whether the Northeast and the Southeast were being singled out. “The effort here is not to try to expel or kick out,” said Blackwell, contrasting it with last year’s debate, which would have resulted in state-level groups being outright denied membership in NCAI.NCAI’s 81st Annual Convention and Marketplace kicked off this past weekend with special pre-conference events to bring together tribal leaders, sponsors, and philanthropic partners. (1/3) pic.twitter.com/250S7wXzQ6

— National Congress of American Indians (@NCAI1944) October 30, 2024

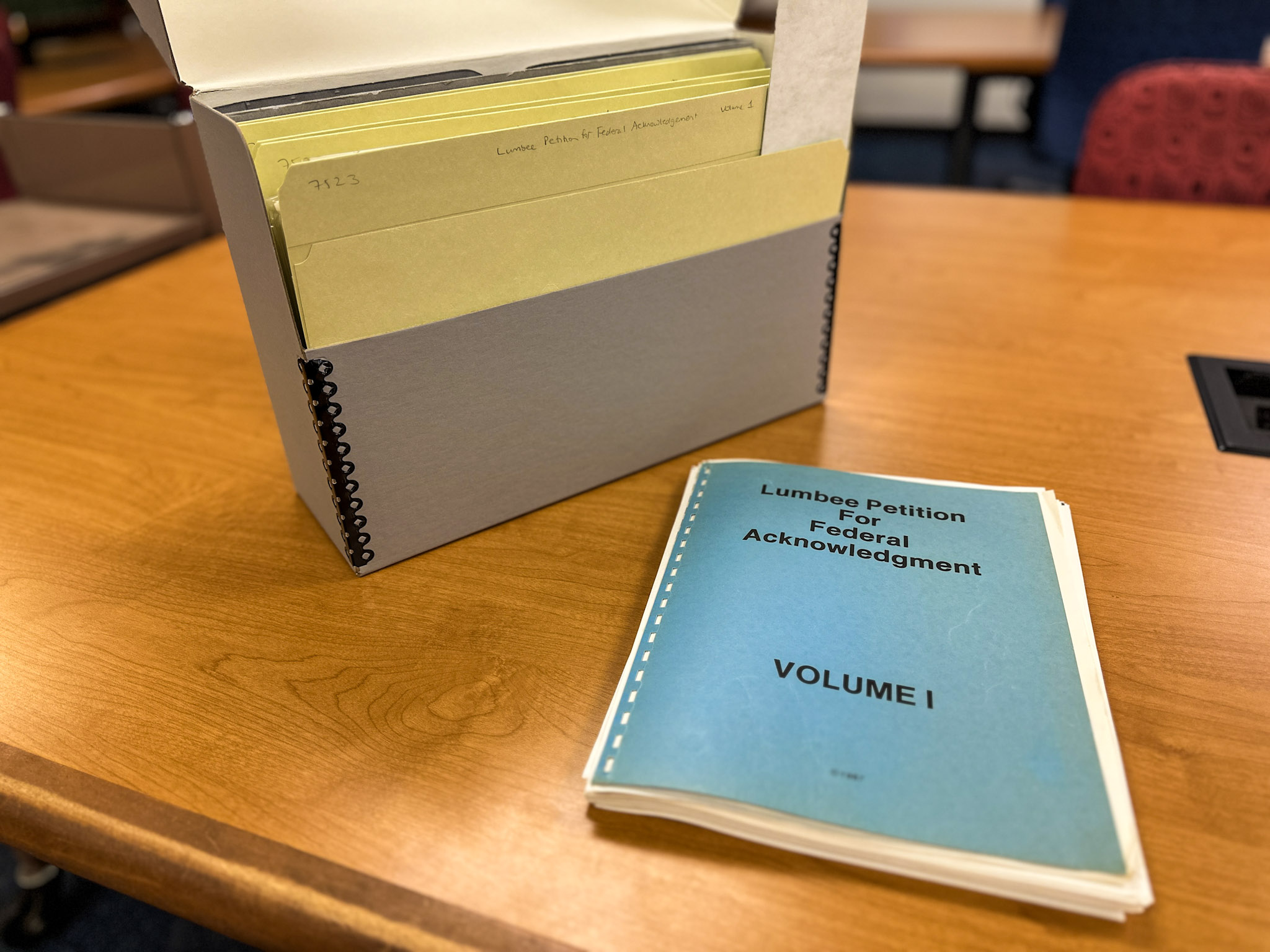

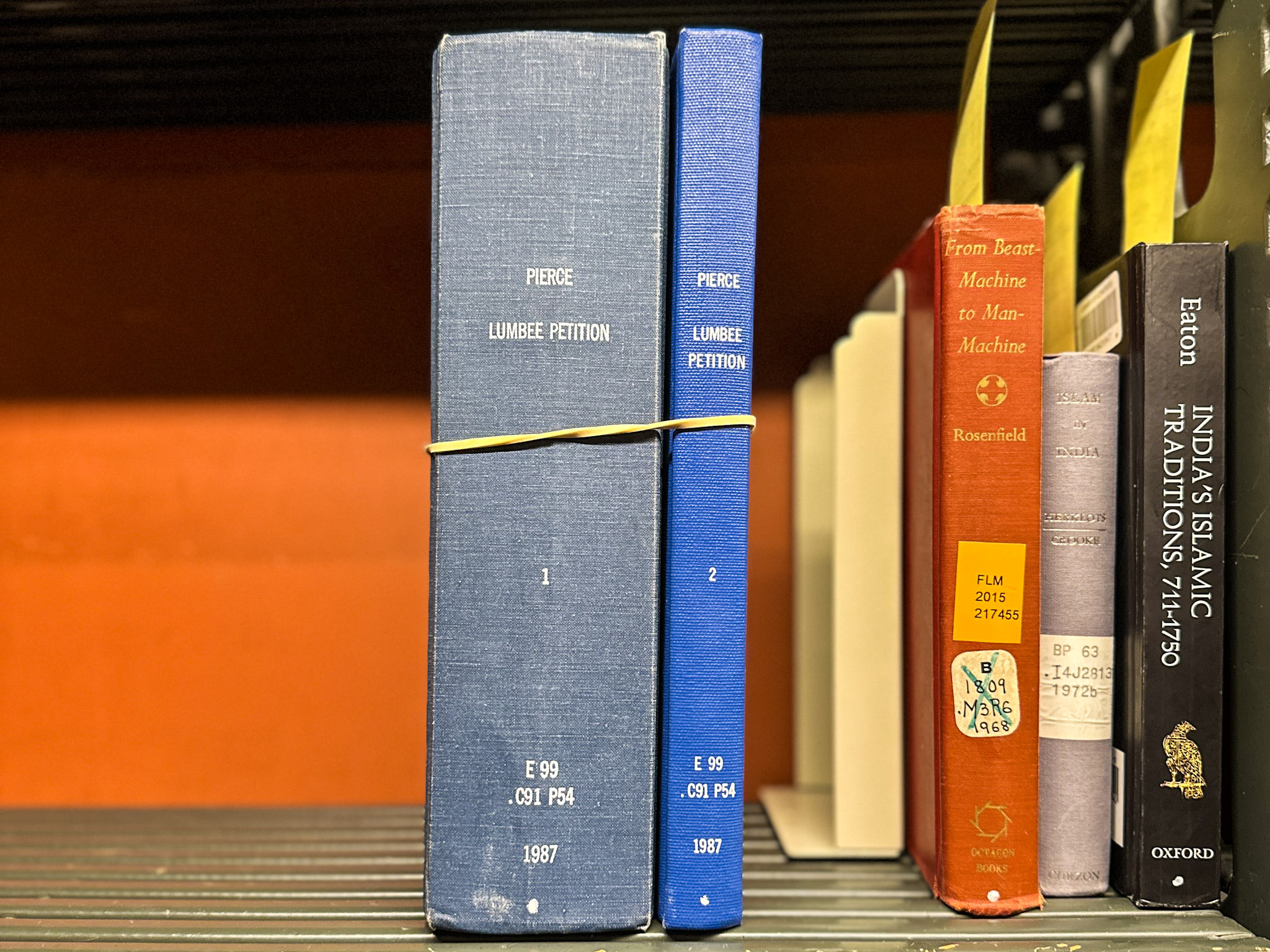

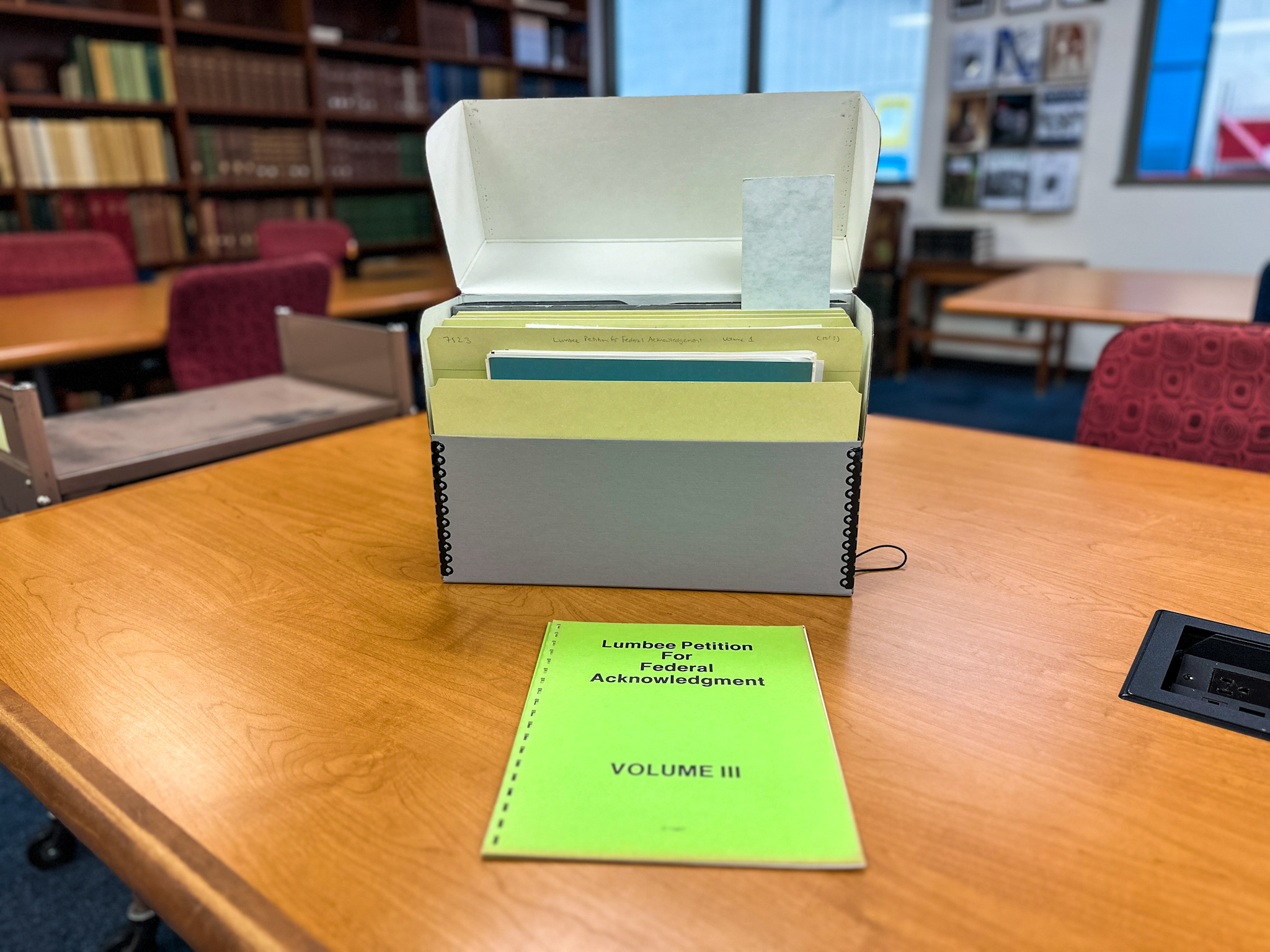

Macarro also pointed out that NCAI’s existing by-laws do not appear to allow for the organization to “expel” any members. He said every member must renew its application every year — which typically happens right before the annual convention. And while Macarro, during the debate last year, supported the proposal to restrict membership in NCAI to federally-recognized tribes, he was adamant that the organization does not “determine who’s an Indian, who’s not an Indian.” “That is outside the provenance of NCAI,” said Macarro, who has served as chair of his tribe, the Pechanga Band of Indians in southern California, for more than 28 years. He further noted that NCAI does not take on “issues that are tribe versus tribe.” That’s why he said the organization issued the apology to the Lumbee Tribe for the materials that were distributed at the convention in Las Vegas. The rebuke from NCAI, however, is not stopping the efforts of tribes who oppose legislative recognition for the Lumbees. As Congress returns to work following the November 5 election, they will be lobbying lawmakers against the bill, known as the Lumbee Fairness Act. [S.521 | H.R.1101] “The Eastern Band of Cherokee has repeatedly stated that federal acknowledgment of groups claiming to be tribes is a serious matter,” Principal Chief Hicks said in a November 1 statement in support of the research conducted by the United Indian Nations of Oklahoma.Many thanks to our participants from this past weekend's NCAI 81st Annual Convention Fundraiser Golf Tournament! It was a wonderful time for our community to come together in support of the NCAI Foundation's Empowering Leaders Initiative! Stay tuned for more updates from #NCAI81. pic.twitter.com/2eM6xcciCa

— National Congress of American Indians (@NCAI1944) October 28, 2024

You can read the report here: https://www.uinoklahoma.com/defendnativecultures?fbclid=IwZXh0bgNhZW0CMTEAAR2SzMN0Lox4638sVEwU9SpR-kU9OCxdgffnMAPy2X_trLeB38jSKkQYY-E_aem_g3vZe_r93olKXXmzwtjpyQ

Posted by Principal Chief Michell Hicks on Friday, November 1, 2024

According to multiple advocates who work on Indian issues on Capitol Hill, Tillis has even put holds on other tribal bills, preventing them from passing unless he sees action on the Lumbee Fairness Act. When asked about such tactics, which have occurred in the 117th and 118th sessions of Congress, his office did not respond. The Lumbee Tribe also has not responded to inquiries about its legislative strategy. But in his recent message, Chairman Lowery reiterated his support for Tillis and other sponsors of the federal recognition bill. “Senator Tillis and other NC Lawmakers are working hard on the Lumbee Fairness Act,” said Lowery.‼️ URGENT: ‼️

— United Indian Nations of Oklahoma (@IndianNationsOK) October 30, 2024

The Lumbee group in North Carolina is actively working to stop federal legislation that would return sacred and historical lands to tribal nations, all to create leverage for their federal recognition bill.

1/

Native America Calling: Tribal museums reflect on tumultuous year, chart their next steps

Press Release: National Museum of the American Indian hosts Native art market

AUDIO: Sea Lion Predation in the Pacific Northwest

Native America Calling: Tribal colleges see an uncertain federal funding road ahead

Native America Calling: Short films taking on big stories

Native America Calling: Advocates push back against new obstacles to Missing and Murdered Indigenous Relatives momentum

Native America Calling: For all its promise, AI is a potential threat to culture

NAFOA: 5 Things You Need to Know this Week (November 24, 2025)

Chuck Hoskin: Cherokee Nation invests in rural transportation

Native America Calling: Native candidates make strides in local elections

National Congress of American Indians returns incumbents and welcomes newcomers to leadership

National Congress of American Indians chooses leadership at big convention

‘Not voting is still a vote’: Native turnout drops amid changes in political winds

Native America Calling: Indigenous voices speak up, but have little clout at COP30

More Headlines