Indianz.Com > News > Canadian documentary focuses on ‘Icon’ who based career on Native identity

Canadian documentary focuses on ‘Icon’ who based career on Native identity

Wednesday, October 25, 2023

Indianz.Com

A Canadian news documentary airing at the end of the week focuses on the Native identity claims of one of the most celebrated performers in entertainment history.

Titled “Making an Icon,” the description for the upcoming episode of The Fifth Estate on CBC News does not mention the name of the subject. But multiple Native people who took part in the documentary process told Indianz.Com that it’s about Buffy Sainte-Marie, whose decades-long career in music, television and education rests on her claim of being Cree from the Piapot Cree Nation, one of the First Nations in the province of Saskatchewan.

“An icon’s claims to Indigenous ancestry are being called into question by family members and an investigation that included genealogical documentation, historical research and personal accounts,” the description for the October 27 episode reads.

The documentary comes at a defining time for a performer whose life has been filled with groundbreaking moments. On August 3, Sainte-Marie, who turned 82 earlier this year, surprised her followers by declaring her “retirement from live performance. The announcement cited “travel-induced health concerns and performance-inhibiting physical challenges” facing the aging musician.

“I have made the difficult decision to pull out of all scheduled performances in the foreseeable future,” Sainte-Marie said as part of the announcement, which resulted in the cancellation of a slew of previously scheduled shows.

“Arthritic hands and a recent shoulder injury have made it no longer possible to perform to my standards,” added Sainte-Marie, whose storied legacy includes winning an Academy Award for the “Up Where We Belong” song from the film “An Officer and a Gentleman.”

“Sincere regrets to all my fans and family, my band and the support teams that make it all possible,” Sainte-Marie concluded.

https://twitter.com/BuffySteMarie/status/1687228690147495936

But the Native people who participated in CBC’s documentary process believe Sainte-Marie’s decision to step away from the spotlight is directly connected to the questions about her First Nations identity. According to the sources, work on the hour-long episode began more than a year ago and it grew to include interviews with individuals in the United States, where the performer was raised following claims to have been born in Canada and adopted out of Piapot.

Due to the lengthy production time associated with the CBC project, Sainte-Marie would have been well aware of the nature of the documentary — especially of its potential to unravel a career that began in the 1960s, the people said. The award-winning singer and songwriter has largely remained silent about her retirement decision, with no significant interviews appearing in mainstream media since her announcement more than two months ago.

But on October 14, Sainte-Marie appeared on a podcast in which she undermined her own long-running claims about her Native heritage. In an interview with Terry David Mulligan, a Canadian actor and radio and television personality who described the singer as one of his “good friends,” she said she wasn’t adopted out of the Piapot Cree Nation as she has often asserted.

“I’m always trying to clarify the urban legend stories because some of them are just not true and others are confusing,” Sainte-Marie said on the podcast, seemingly indicating that it’s the public that has not understood her Native claims.

“I think there’s been confusion regarding my Piapot adoption, for instance,” Sainte-Marie said of her connection to an elderly Cree couple that welcomed her into their family after she rose to prominence as a folk singer. “I was adopted into the Piapot family — not I was adopted out of Piapot Reserve.”

“And that makes a big difference,” she said.

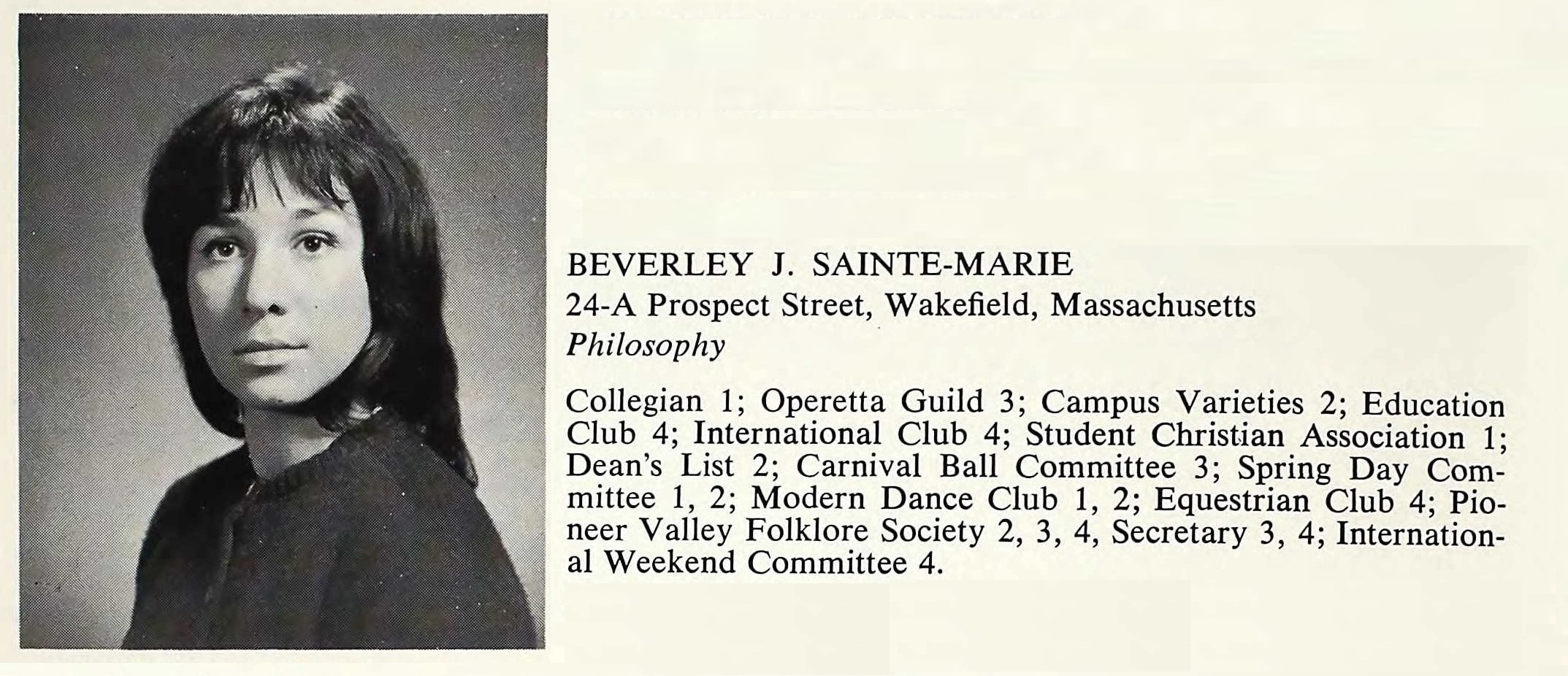

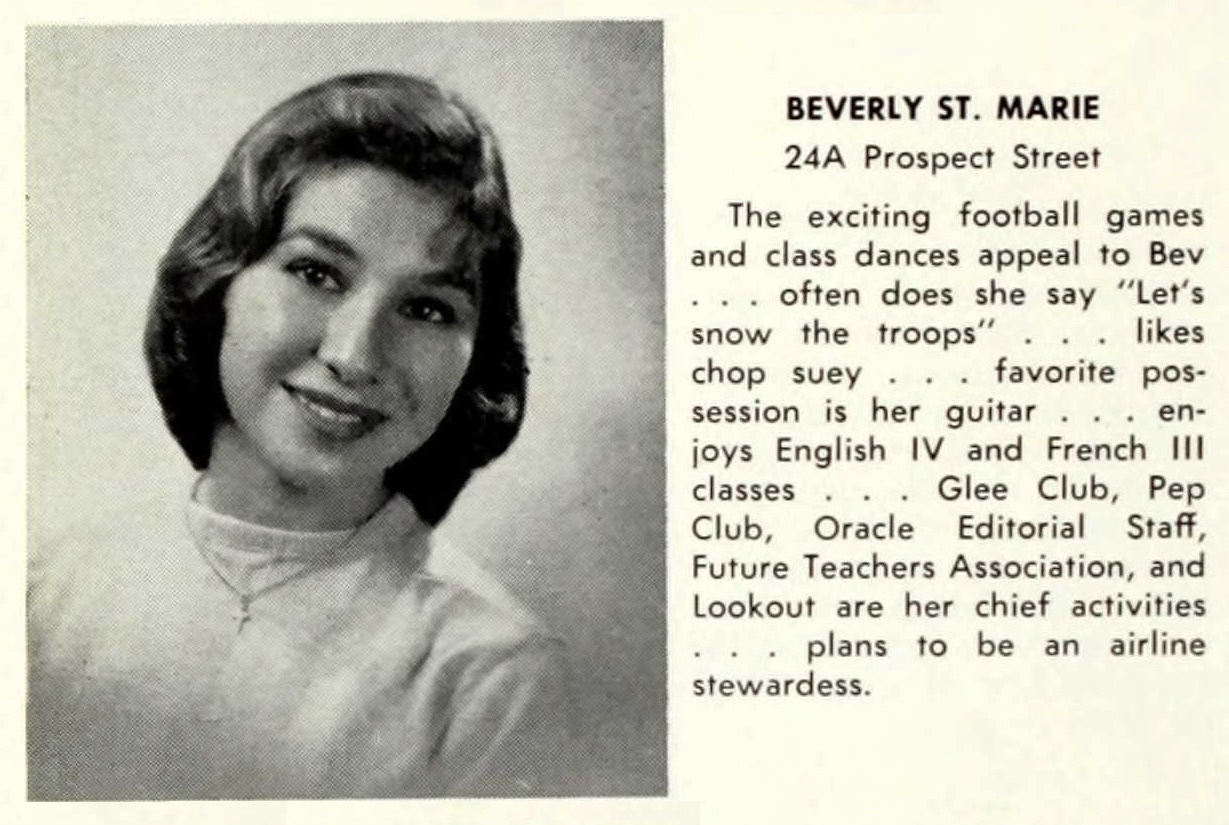

In the months since the The Fifth Estate began its investigation for CBC, additional information has cast doubt on Sainte-Marie’s narrative. As referenced in the show description, “family members” appear to have been the source of some of the unraveling of the icon’s past. Sainte-Marie’s son from her marriage to Sheldon Peters Wolfchild, a Dakota actor, activist and filmmaker from Minnesota, has repeatedly stated on social media that his biological mother attained her Native identity through “naturalization” — not by birth to Native parents. He has affirmed her admission that she was adopted into a Cree family, contradicting her association with the era of forced removals and adoptions, a story she repeated on a CBC program in 1994. Her son further stated that Sainte-Marie and her family have long claimed descent from Indigenous people in New England, echoing the “part Micmac” quote from the biography published over a decade ago. He himself has asserted on social media that he has “East Coast Native DNA / blood / ancestry” — the source of which would be his biological mother. In an effort to confirm the “part Micmac” lore, another family member — Sainte-Marie’s younger sister — shared online that she took a commercial DNA test through Ancestry.Com, the largest for-profit genealogy company in the world. In discussing the results, she said she is biologically “related” to Wolfchild’s son, a scenario that would be impossible if her famous sibling’s “Big Scoop” narrative were factual. The sister revealed that she uploaded the DNA data files from her Ancestry.Com test to GEDMatch, a popular website used for genetic genealogy and family tree research. In one of her posts on social media, she even shared the unique identifier associated with her “kit” — as the results are known on the site. Using the unique identifier, the sister’s DNA kit was viewed by Indianz.Com. They results show almost no American Indian component in the Sainte-Marie family’s genetic makeup, undercutting the claim of being “part Micmac” that appeared in the 2012 biography and in early news stories about the singer known around the world as “Buffy.” The opening sentence of the more recent “authorized” biography also has been cast into doubt by the discovery of an official record of Sainte-Marie’s birth. The document, a copy of which was viewed by Indianz.Com, shows a female child named “Beverley Jean Santamaria” having been born to father Albert Santamaria and mother Winifred Irene Kenrick on February 20, 1941 — the birthdate that Buffy has accepted as her own. According to the official record of Sainte-Marie’s birth, Beverley Jean Santamaria was born at the New England Sanitarium and Hospital in Stoneham, Massachusetts. The facility, which shut down in 1999, was only about 10 miles from the family’s home at the time in North Reading. The defunct hospital was recorded to be the same place of birth as a male child whom Albert and Winifred lost as an infant at just four months of age, a tragic detail included in the 2012 biography. These two Santamaria children and their years of birth — 1940 for Wayne and 1941 for Beverley — are listed in the Massachusetts birth index, a book based on official records from the state government. Likewise, the family’s use of the “Sainte-Marie” name is contradicted by information that wasn’t contained in either of the biographies. According to the 2012 biography, the Santamarias became “St. Marie” in an effort to avoid “anti-Italian prejudice” following World War II. The claim is attributed in the book to Buffy’s younger sister, the one who took the DNA test. However, the U.S. Census from 1950, which only became publicly available on April 1, 2022, shows the family was still officially using the “Santamaria” surname — some five years after the end of the world conflict. Buffy’s younger sister was reported to be one year of age at the time of the national count. By this time, the Santamarias, including an older male child born in 1936, had moved to Wakefield, not far from North Reading, where they were living in 1940. The 2012 book further claims that Buffy starting using the “French spelling, Sainte-Marie,” in order to protect her family when she became “famous and controversial” as a folk singer known for speaking her mind on political and cultural issues. But one of the earliest news reports featuring the name “Buffy Sainte-Marie” dates to 1960 — when she was part of the “Operetta Guild” as a student at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst, located in the western part of the state. A 1961 story reported “Buffy Sainte-Marie” being a student who took part in a theater production at a nearby college.In case you haven’t heard, on October 27th, there just maybe a cosmic shift in the Indigenous universe. According to rumour, CBC’s Fifth Estate will be taking a close look at Buffy Sainte-Marie’s Indigenous ancestry. If true, Black will be white, up will be down.

— Drew Hayden Taylor (@TheDHTaylor) October 23, 2023

Buffy Sainte-Marie – In her own words

A clip from CBC’s Adrienne Clarkson Presents. Aired March 15, 1994.

“I was apparently born in Saskatchewan, adopted away. I was raised in Maine, in Massachusetts, and as much as I’ve been able to put together, I do come from this area.

I’m not positive of how I’m genetically related to the family

who has since become my family. But there’s a tradition in Cree culture,

which is quite different from the European tradition, and adoption is taken

really seriously, probably even more seriously than marriage.

And if if a family loses a child, if a child dies,

then those parents are always leave that

space in their hearts open to be filled

by another life, by another child.”

Search

Filed Under

Tags

More Headlines

Native America Calling: A sample of Native Guitars Tour 2024

Native America Calling: How Native literature is changing the mainstream narrative

Native America Calling: No ordinary animal

Native America Calling: Safeguards on Artificial Intelligence

NAFOA: 5 Things You Need to Know this Week

Chuck Hoskin: Cherokee Nation takes the lead for our environment

Native America Calling: Earth Day assessment for Native peoples

Cronkite News: Gathering addresses ‘epidemic’ among Native people

VIDEO: Cody Desautel on tribes and federal forest management

AUDIO: Legislative Hearing on Discussion Draft of Forest Management Bill

Native America Calling: Remembering the 1974 Navajo border town murders

Native America Calling: Can the right approach close the Native immunization gap?

Cronkite News: Long COVID cases remain high in Arizona

Native America Calling: Eyes in the sky for development, public safety, and recreation

Native America Calling: Three new films offer diverse views of Native life

More Headlines

Native America Calling: How Native literature is changing the mainstream narrative

Native America Calling: No ordinary animal

Native America Calling: Safeguards on Artificial Intelligence

NAFOA: 5 Things You Need to Know this Week

Chuck Hoskin: Cherokee Nation takes the lead for our environment

Native America Calling: Earth Day assessment for Native peoples

Cronkite News: Gathering addresses ‘epidemic’ among Native people

VIDEO: Cody Desautel on tribes and federal forest management

AUDIO: Legislative Hearing on Discussion Draft of Forest Management Bill

Native America Calling: Remembering the 1974 Navajo border town murders

Native America Calling: Can the right approach close the Native immunization gap?

Cronkite News: Long COVID cases remain high in Arizona

Native America Calling: Eyes in the sky for development, public safety, and recreation

Native America Calling: Three new films offer diverse views of Native life

More Headlines