Indianz.Com > News > Self-described ‘agitator’ changes tribal affiliation story after inquiries

From ‘Chahta’ to ‘Indigenous’ in America’s largest city

Self-described ‘agitator’ changes tribal affiliation story after inquiries

Friday, February 25, 2022

Indianz.Com

PRETENDIAN COUNTRY TODAY: Looking for exclusive, behind the scenes content on Regan de Loggans? Join Indianz.Com on Substack for all the latest.

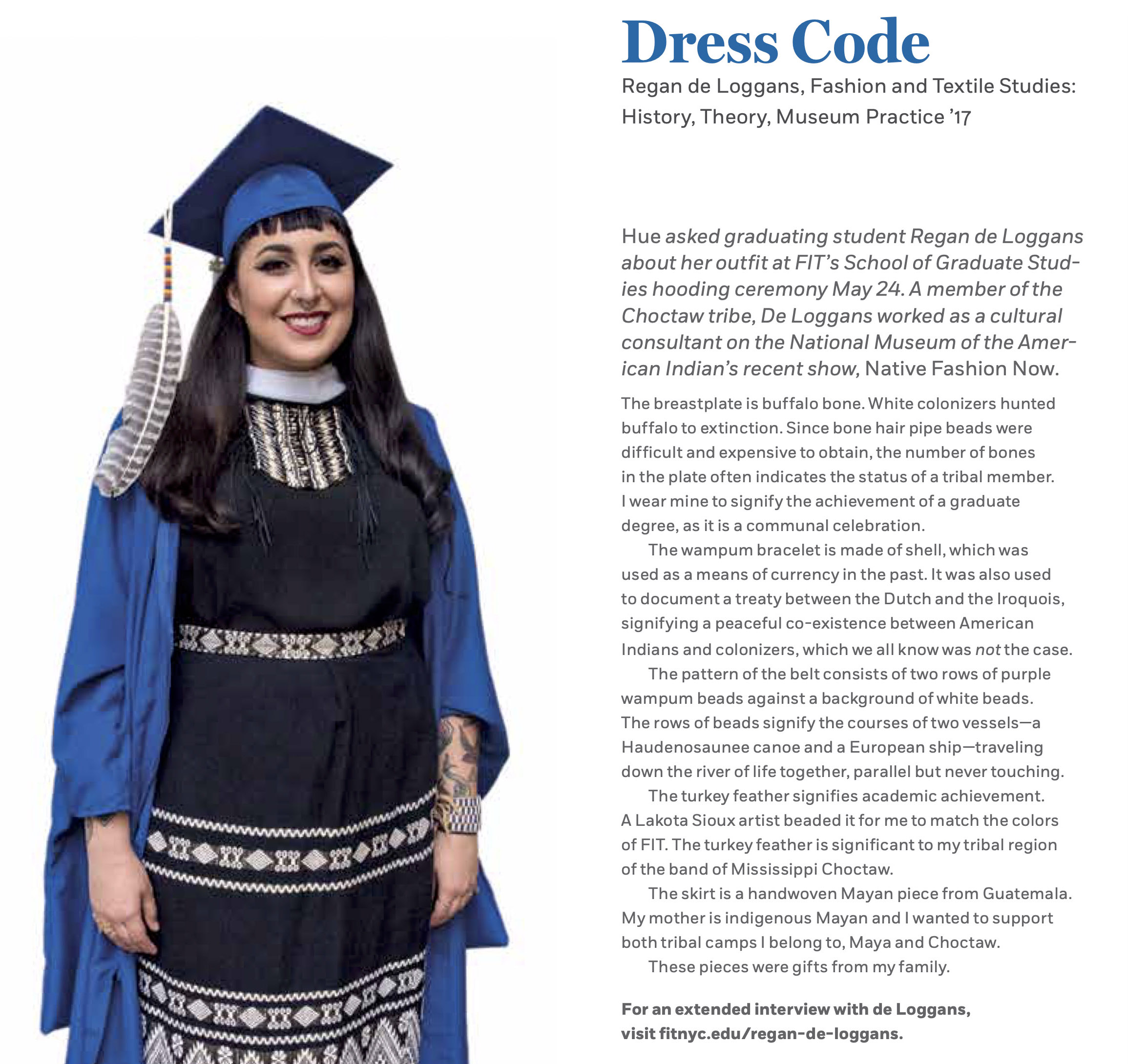

The leader of New York City’s most prominent and vocal Indigenous group fabricated their tribal affiliation after taking a DNA test, an investigation by Indianz.Com has found. Asserting a “Mississippi Choctaw” tribal identity in America’s most populous city has opened numerous doors for Regan Brook Loggans. Through a group known as the Indigenous Kinship Collective, the German-born U.S. citizen has solicited tens of thousands of dollars in donations, exploited professional opportunities and has frequently shamed the public into amplifying their ever-growing platform. Yet prior to the DNA test, Loggans did not identify as American Indian, according to long-time friends and long-time associates. They even stylized their surname with “de” in hopes of drawing attention to Guatemala, their mother’s country of origin. “Regan told everyone it was a ‘Guatemala’ thing,” an associate told Indianz.Com of the “de Loggans” invention. The Guatemala connection is one source of Loggans’ shifting identity claims. A recent hiring announcement from The Vera List Center for Art and Politics at The New School, as well as a biography for the Resistance Radio show describing them as “a Native living in the City,” make references to the K’iche’ Maya, a specific group of indigenous people in the Central American nation. Yet it was a commercial genetic testing company that spurred the self-described “agitator” to expand their affiliation to a tribal nation in the United States, the investigation shows. According to a person with direct knowledge of the exchange, the 23AndMe test kit was purchased by Loggans’ father, Ron Loggans, an experienced journalist who has long identified himself as White in public records since the 1980s. The elder Loggans is originally from Mississippi but spent more than a decade working overseas, where two of his children, including Regan, were born. After taking the DNA test in 2013, the results of which were obtained by Indianz.Com, Regan Loggans began claiming to be from the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, one of the three federally recognized tribes with ties to the historic Choctaw Nation. Long-time friends and associates say this new identity was used to gain entry into professional spaces, including the National Museum of the American Indian in New York City, where Loggans once served as a “cultural consultant” for an exhibit on Native fashion. “You can’t make a decision on tribal affiliation based on a DNA test,” Dr. Kim Tallbear, a citizen of the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate who has written and spoken extensively on the use — and misuse — of commercial genetic testing, told Indianz.Com.

Following the inquiries, Loggans deleted a significant reference to their supposed tribal affiliation from social media. The phrase “Chahta Sia Hoke” — meaning “I am Choctaw” — had long appeared on Instagram, where they built a large audience over the last four years, primarily based on “Indigenous” content. Loggans also began untagging their account from other Instagram posts in which they had been identified as “Choctaw,” according to a review of the platform. Around the same time, Loggans independently contacted Indianz.Com and asked to “talk.” But immediately following the request, they deactivated the Instagram profile entirely, leaving no easily visible trace of numerous posts about colonization, cultural appropriation and other Native-related issues. Still, the story changed a third time once Indianz.Com asked about the status of the account, whose name includes a variation on an anti-LGBTQ slur. Loggans revived the account and told followers that they were being “targeted” by unnamed individuals. “I will not be bullied out of community by those who don’t know me and have made no attempt to know me,” Loggans wrote in an Instagram story, a less-permanent version of an Instagram post, just days after sending a statement to Indianz.Com. Despite the recent changes, a digital footprint of the shifting tribal affiliation claims exists through the Indigenous Kinship Collective, whose most outspoken and prominent member continues to be Loggans. The group positions itself as an inclusive and welcoming space for people of all backgrounds in New York City, where fewer than 1 percent of the population of 8.8 million identifies as American Indian or Alaska Native.Happy New Year! We're excited to announce the recent expansion of our team. With the VLC now in its 30th year, we're thrilled to move forward with an even greater capacity for curatorial, editorial, and community-driven work. Read more here! https://t.co/TrfjLdKKvS

— Vera List Center (@VeraListCenter) January 11, 2022

Through very public displays of activism, the group also functions as a conscience of New York City when it comes to Native issues, even criticizing other Native people — most notably a prominent Cree artist from Canada — whose beliefs and behaviors are deemed to be out of line. The collective’s actions tend to draw attention in non-Native media as a result of Loggans’ prominence and willingness to be the “agitator,” supposedly on behalf of other Indigenous residents of the city. “Her actions were openly harmful to Natives and manufactured so many instances of open hostility,” one Native woman who spoke anonymously out of fear of retaliation from Loggans told Indianz.Com. “Native women got arrested due to her actions,” the person added, referring to events that Loggans organized under the banner of the “Indigenous” collective. Multiple people who spoke to Indianz.Com described the efforts as going even further. They said Loggans has weaponized the group to bully other Native people who aren’t seen as loyal enough to Loggans and their inner circle. Most of the victims are Native women who end up being ostracized after asking questions about the collective’s finances, vision and backgrounds of others in the inner circle. While Loggans told Native Max Magazine that their collective “started in 2018 after an Indigenous womxn’s gathering” it was born out of the work of a different Native woman, documents and interviews with numerous people who had first-hand knowledge of the event show. Noel Altaha, a citizen of the White Mountain Apache Tribe, organized the “Indigenous womxn’s gathering” mentioned in the article through a grant received by the American Indian Community House. At the direction of AICH, which was founded in 1969 to serve American Indians and Alaska Natives in New York City, Altaha told Indianz.Com that she was tasked in January 2018 with organizing a meeting for Native women in the business sector. But as her efforts continued throughout the year, she said she broadened the focus to an “indigenous womxn’s gathering.”

More recently, Altaha has been speaking publicly about what she calls the theft of her work by Loggans, who functions as the de facto leader of the Indigenous Kinship Collective. The second individual no longer appears regularly with the group, having disclaimed the affiliation with a tribal nation. “I want people to know the impact this has,” Altaha said of the takeover of the group by individuals whose tribal identity claims only recently surfaced. “Spiritually and physically, this is deep.” Melissa Iakowi:he’ne’ Oakes, a Mohawk woman who was born and raised on her nation’s territory of Akwesasne, has dedicated her life to advancing Native causes in New York City and throughout the state of New York. She witnessed first-hand the takeover of the collective by Loggans and said it’s indicative of a long-standing problem. According to Oakes, organizations based on Native lands in the U.S. deserve leadership from peoples of those lands. Anything else, she asserted, contributes to the “erasure” of Onkwe:hon:we’, which means “original people” in her language. “I don’t know of any Onkwe:hon:we’ who would go to another country and claim to be indigenous from there and claim leadership in spaces that are allocated for, and reserved for, Native people,” said Oakes, a mother of two from the Snipe Clan of the Mohawk people. “To me, that’s really settler mentality where they are chasing a dream and they think they are entitled to anything and everything in their wake,” Oakes added.Do Not Support/Fund the Indigenous Kinship Collective's thievery https://t.co/7XikDJMOyc via @indianz

— Noel Altaha (@NoelAltaha) December 5, 2021

To Oakes, whose Mohawk name translates to “She gathers and organizes people,” the problem extends beyond activist spaces like the Indigenous Kinship Collective. Universities and museums, for example, are failing to engage adequately with tribal nations even as they acquire and allocate resources on initiatives and efforts directed toward American Indians and Alaska Natives, she said. “I challenge all museums, institutions, universities and foundations to do the work, to start vetting to make sure that you are actually giving back to Natives from this land,” said Oakes. In recent years, Oakes has appeared as a speaker and guest lecturer at The New School in New York City, where The Vera List Center for Art and Politics (VLC) is housed. She noted that the center’s Borderlands Fellowship initiative does not include any representation from tribes in New York, including those whose territories have been separated by the modern-day colonial borders. “It’s insulting that the Haudenosaunee that are on the border of U.S. and Canada are left entirely out of this conversation,” Oakes said of the center’s “borderlands” work, which has been expanding with the help of outside funding. “This opportunity could be super impactful if they had worked with one of us,” said Oakes, who now serves as director of the North American Indigenous Center of New York, whose mission is centered on furthering tribal priorities, such as land stewardship. “It’s just really insulting that they didn’t even try to connect with tribal communities in New York,” Oakes said of the VLC.

As for the Indigenous Kinship Collective, the group last week told its nearly 23,000 followers on Instagram that they are “currently on collective rest from social media engagement.” The February 15 post was the first since January 18. And just as with the June-July social media respite of 2019, the group announced a change to their priorities. The post reads: “We are shifting our focus and in this process, we will no longer be accepting donations towards our mutual aid fund.” Loggans, during a virtual presentation hosted by The Vera List Center in February 2021, had said the collective had collected significant sums of money for the group’s “mutual aid fund.” A post from October 7, 2021, put the amount at “over” $75,000. According to the post, the group sent “almost 2k directly to out kin on the frontlines at line 3,” where Loggans had spent significant time over the last year. Court documents show their arrests occured in March, August and September of 2021. In addition to asking Indianz.Com not to publish a story, Loggans asked for their statement to be published “unaltered.” It follows, in full:

I am born of a Maya woman from Guatemala and a father of Choctaw descendancy. I have not claimed to be enrolled because I do not believe it is my place to be enrolled when I did not grow-up in community, especially considering the violent and racist legacy blood quantum has maintained within Indigenous communities. I find that this piece and its author are engaged in lateral violence and causing harm to Indigenous communities by conflating Indigeneity with enrollment and allowing white people to gatekeep who is Indigenous.

I did take a DNA test in 2013, which does illustrate Indigenous ancestry, though that is not what I use as my claim to community because blood quantum is racist. The claims made about me appear to usurp community protocol by deferring to a white woman, who made an incorrect comparison about MY Indigeneity, thus furthering colonial gatekeeping of Indigenous identities. As we all know, white people are not (or should not be) gatekeepers of Indigeneity, in the same way that enrollment is not the pinnacle of proof of Indigeneity. My Indigeniety is not solely tied to Indigenous communities of the North, and erasing that complexity is inherently racist. We, Indigenous people of South and Central America, are too often flattened under the colonial descriptor of Latinidad. Delegitimizing my Indigeneity seeks to center North American Indigenous communities as the standard of nativeness.

We all know colonial ideologies of Indigeneity are harmful to the community, and unfortunately, Acee Agoyo of Indianz.com, appears to be conflating my experience through colonial definitions and publishing known untruths.

Search

Filed Under

Tags

More Headlines

Chuck Hoskin: Cherokee Nation invests in our citizens

Native America Calling: 2026 State of Indian Nations

Native America Calling: New art exhibitions offer creative interpretations of Native survival and endurance

AUDIO: Legislative Hearing to receive testimony on S.2098, S.1055 & S.699

VIDEO: Legislative Hearing to receive testimony on S.2098, S.1055 & S.699

Native America Calling: Can caribou slow the drive for oil and mineral development in Alaska?

Cronkite News: Judge questions targeting of Democratic lawmaker

Testimony: Leanndra Ross of Southcentral Foundation

Testimony: Dayna Seymour of Colville Tribes

Testimony: Darrell LaRoche of Indian Health Service

Senate Committee on Indian Affairs hosts hearing for tribal health bills

Native America Calling: College Native American Studies programs map their next steps

AUDIO: Making Federal Economic Development Programs Work in Indian Country

Gaylord News: Immigration agents sweep into Indian Country

Witness List: Making Federal Economic Development Programs Work in Indian Country

More Headlines

Native America Calling: 2026 State of Indian Nations

Native America Calling: New art exhibitions offer creative interpretations of Native survival and endurance

AUDIO: Legislative Hearing to receive testimony on S.2098, S.1055 & S.699

VIDEO: Legislative Hearing to receive testimony on S.2098, S.1055 & S.699

Native America Calling: Can caribou slow the drive for oil and mineral development in Alaska?

Cronkite News: Judge questions targeting of Democratic lawmaker

Testimony: Leanndra Ross of Southcentral Foundation

Testimony: Dayna Seymour of Colville Tribes

Testimony: Darrell LaRoche of Indian Health Service

Senate Committee on Indian Affairs hosts hearing for tribal health bills

Native America Calling: College Native American Studies programs map their next steps

AUDIO: Making Federal Economic Development Programs Work in Indian Country

Gaylord News: Immigration agents sweep into Indian Country

Witness List: Making Federal Economic Development Programs Work in Indian Country

More Headlines