Indianz.Com > News > Museum won’t verify claims of tribal ancestry after artists withdraw from show

Museum won’t verify claims of tribal ancestry after artists withdraw from show

Native women raised alarms about exhibition in Massachusetts

Wednesday, June 2, 2021

Indianz.Com

The Fruitlands Museum in eastern Massachusetts doesn’t plan on verifying whether the artists it works with have connections to the tribes they claim even after two individuals withdrew from a new show.

Gina Adams, who claims to be Ojibwe and Lakota, and Merritt Johnson, who claims to be Mohawk, removed their works from “Echoes in Time: New Interpretations of the Fruitlands Museum Collection” when questions were raised about their tribal affiliations, The Boston Globe first reported in a story posted online on Tuesday. Neither are enrolled with any of the Indian nations they claim but a director at the facility doesn’t plan on changing how such matters are handled.

“I personally would not, nor would I recommend a curator call the tribe to verify,” Jessica May, the managing director of art and exhibitions at the Fruitlands Museum, told The Globe.

“I expect that if they claim that identity as their own, they are doing so truthfully,” May told the paper.

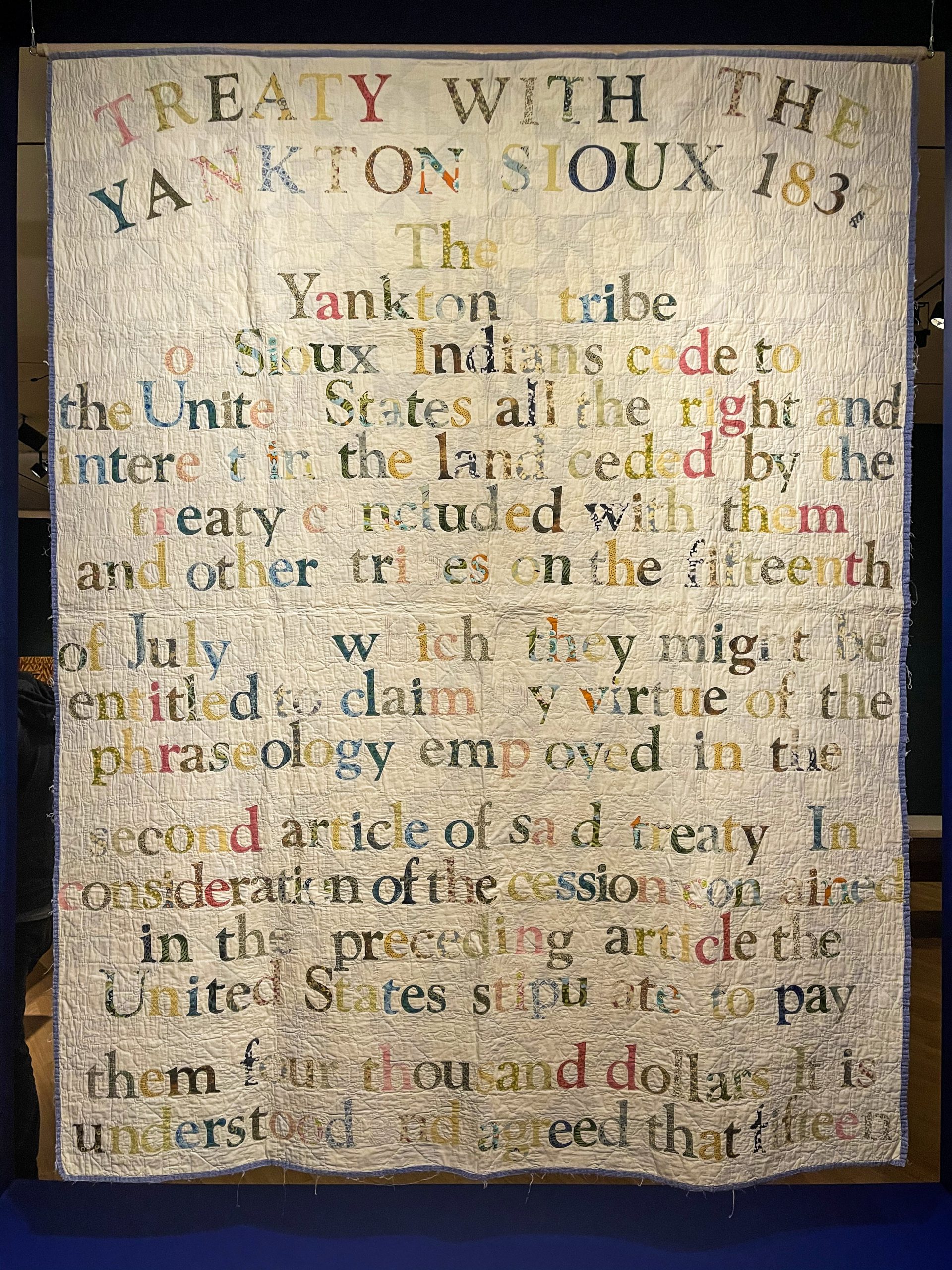

Even though Adams, who is an assistant professor and an assistant dean at Emily Carr University in Canada, withdrew her works, she is still credited as a co-curator of the show, which opens on Saturday. The way Fruitlands has handled the matter doesn’t sit well with the Native women who raised concerns about the exhibition, The Globe reported. “I think they totally dropped the ball,” Leah Hopkins, a citizen of the Narragansett Tribe who is an administrator at the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology at Brown University, told the paper. “I’ve seen this happen so many times. It’s 2021. We’ve got to get with it.” Although Hopkins serves on the Fruitlands Museum’s Native American Advisory Team, she told the paper that she was never informed about “Echoes in Time” in the first place. She didn’t know Adams was involved either, The Globe reported. “We were completely in the dark about this,” Hopkins told the paper of the four-person Native advisory team. Two other Native women also approached the Fruitlands Museum about the show, The Globe reported. Adams claims to be related to two Ojibwe leaders who signed the Treaty with the Chippewa of the Mississippi in 1867. She created a “Broken Treaty Quilt” in memory of her purported ancestors. “The Treaty with the Chippewa of the Mississippi 1867 Broken Treaty Quilt has deep meaning to our family as our great great grandfather Waabaanaquot signed the treaty, as did a great great uncle Mishugiiziguk,” Adams says in an artist’s statement.Native American artists want the Fruitlands Museum to scrutinize artist and co-curator Gina Adams’s account of Ojibwe heritage. https://t.co/XniRAcvfqC

— The Boston Globe (@BostonGlobe) June 1, 2021

A number of her works are marketed as being available for sale, raising questions about compliance with the Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990. The federal law requires works marketed as Native to have been produced by a Native artisan, which is defined as a citizen of a federally- or state-recognized tribe, or by an artist certified as such by a tribal nation. “Under the Indian Arts and Crafts Act it is illegal to market art or craft products in a manner that falsely suggests it is Native American produced if it is not,” Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, who is the first Native person to serve in a presidential cabinet, says in a video in support of Indian artists. An individual who was quoted in The Globe article represents Adams in the commercial art market. One of the Native women who raised questions about the Fruitland Museum show in fact asked the other co-curator, Shana Dumont Garr, whether the federal law was taken into account. “I asked Shana if she’d done any due diligence, if she’d followed the Indian Arts and Crafts Act and checked what [Adams’s] tribal enrollment or status is, and she said she had not,” Erin Genia, a citizen of the Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate, told The Globe. As for Johnson, she too admits that she is not enrolled in the St. Regis Mohawk Tribe, based in New York, or with any of the Mohawk Nations across the border in Canada. Her biography asserts that she is “not claimed by, nor a citizen of any nation from which she descends.”

A recent virtual talk which was to feature Johnson and her work, which relies heavily on her experience as a person of “mixed” ancestry, was marked as “CANCELLED” by Simon Fraser University Like the educational institution where Adams works as a professor, SFU is located in the province of British Columbia in Canada. Johnson is also represented by Accola Griefen Fine Art, the same as Adams. Emily Carr University described Adams’ hiring in 2019 as a means of “Indigenizing” the campus. She was touted as one of four full-time Indigenous faculty members at the time. The “Echoes in Time” show in Massachusetts features “sixteen contemporary artists of Indigenous descent from throughout North America,” according to the Fruitlands Museum website. Participants include:

Norman Akers (Osage)

Marwin Begaye (Diné/Navajo)

Gregg Deal (Pyramid Lake Paiute)

Betsey Garand (French Canadian, English, Abenaki)

Brenda Garand (French Canadian, English, Abenaki)

Mimi Gellman (Anishinaabe/Ojibwe, Ashkenazi Jewish, Metis)

Margaret Jacobs (Akwesasne Mohawk)

George Longfish (Seneca, Tuscarosa)

Jacob Meders (Mechoopda/Maidu)

Dillen Peace (Diné/Navajo)

Sydney Jane Brooke Campbell Maybrier Pursel (Ioway)

Theresa Secord (Penobscot)

Alicia Smith (Xicana)

Alana Tapaha (Diné /Navajo)

Summer Zah (Navajo, Jicarilla Apache, Choctaw)

The exhibit runs through December 6.

Marwin Begaye (Diné/Navajo)

Gregg Deal (Pyramid Lake Paiute)

Betsey Garand (French Canadian, English, Abenaki)

Brenda Garand (French Canadian, English, Abenaki)

Mimi Gellman (Anishinaabe/Ojibwe, Ashkenazi Jewish, Metis)

Margaret Jacobs (Akwesasne Mohawk)

George Longfish (Seneca, Tuscarosa)

Jacob Meders (Mechoopda/Maidu)

Dillen Peace (Diné/Navajo)

Sydney Jane Brooke Campbell Maybrier Pursel (Ioway)

Theresa Secord (Penobscot)

Alicia Smith (Xicana)

Alana Tapaha (Diné /Navajo)

Summer Zah (Navajo, Jicarilla Apache, Choctaw)

Search

Filed Under

Tags

More Headlines

Chuck Hoskin: Cherokee Nation helps heal our communities

Native America Calling: Native skin cancer study prompts new concerns about risk

South Dakota Searchlight: Trump terminations hit Indian Arts and Crafts Board

Native America Calling: Regional improvement in suicide statistics is hopeful sign

List of Indian Country leases marked for termination by DOGE

‘Let’s get ’em all done’: Senate committee moves quickly on Indian Country legislation

AUDIO: Senate Committee on Indian Affairs Business Meeting to consider several bills

VIDEO: Senate Committee on Indian Affairs Business Meeting to consider several bills

Native America Calling: The ongoing push for MMIP action and awareness

‘Blindsided’: Indian Country takes another hit in government efficiency push

Native America Calling: A new wave of resistance against Trans Native relatives

Urban Indian health leaders attend President Trump’s first address to Congress

‘Mr. Secretary, Why are you silent?’: Interior Department cuts impact Indian Country

Cronkite News: Two Spirit Powwow brings community together for celebration

Native America Calling: Native shows and Native content to watch

More Headlines

Native America Calling: Native skin cancer study prompts new concerns about risk

South Dakota Searchlight: Trump terminations hit Indian Arts and Crafts Board

Native America Calling: Regional improvement in suicide statistics is hopeful sign

List of Indian Country leases marked for termination by DOGE

‘Let’s get ’em all done’: Senate committee moves quickly on Indian Country legislation

AUDIO: Senate Committee on Indian Affairs Business Meeting to consider several bills

VIDEO: Senate Committee on Indian Affairs Business Meeting to consider several bills

Native America Calling: The ongoing push for MMIP action and awareness

‘Blindsided’: Indian Country takes another hit in government efficiency push

Native America Calling: A new wave of resistance against Trans Native relatives

Urban Indian health leaders attend President Trump’s first address to Congress

‘Mr. Secretary, Why are you silent?’: Interior Department cuts impact Indian Country

Cronkite News: Two Spirit Powwow brings community together for celebration

Native America Calling: Native shows and Native content to watch

More Headlines