Indianz.Com >

News > Non-Indians assert ‘mestizo’ identity in bid for consultation policy

House Subcommittee on National Parks, Forests, and Public Lands: Legislative Hearing – March 1, 2022

Non-Indians claim ‘mestizo’ identity in bid for consultation policy

Biden administration raises concerns about respecting tribal sovereignty

Tuesday, March 1, 2022

By Acee Agoyo

Indianz.Com

WASHINGTON, D.C. —

A Democratic-led bill working its way through Congress would extend the federal policy of consultation to groups of American citizens who have recently been asserting an Indian identity.

H.R.5493, the Land Grant-Mercedes Traditional Use Recognition and Consultation Act, requires the federal government to consult with non-Indians who consider themselves heirs of

land grants in the state of New Mexico. The land grants, often referred to as

mercedes in the Spanish language, were previously issued by the kingdom of Spain and, later, by the government of Mexico.

Some of the land within the

mercedes has since ended up in the

hands of the United States. The bill addresses how federal agencies manage these areas.

But while H.R.5493 attempts to ensure that the sovereign rights of tribes aren’t impacted by this new consultation policy, the Biden administration is raising some significant concerns. An official from the

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) said the bill could in fact undermine the nation-to-nation relationship between tribal governments and the United States.

“The word ‘consultation’ as it pertains to federal agencies has a specific meaning when relating to federally recognized Indian tribes,” Greg Smith, the director of the Lands and Realty Management for the

U.S. Forest Service, said at a

hearing on Capitol Hill on Tuesday afternoon.

“While the Forest Service strives for better collaboration and cooperation with our traditional communities, the term ‘consultation’ — as used with respect to federally recognized tribes — cannot be applied to this work with land grant-

mercedes,” Smith told members of the

House Committee on Natural Resources, the legislative panel with jurisdiction over Indian issues.

Indianz.Com Audio: House Subcommittee on National Parks, Forests, and Public Lands Legislative Hearing – March 1, 2022

According to Smith, heirs of the historic land grants already play a role in shaping federal management decisions. Pointing to regular meetings with

mercedes, he said forest plans in New Mexico now include a section titled “Northern New Mexico Traditional Communities and Uses” to bring more voices to the table.

But in his written testimony to the

House Subcommittee on National Parks, Forests, and Public Lands, as well as in his verbal presentation, Smith made it clear that the Biden administration is drawing a line when it comes to upholding the federal government’s trust and treaty obligations to tribes and their citizens.

“The Forest Service is committed to collaboration and transparency that address the unique needs of our local communities,” the

written statement reads. “However, our obligation to federally recognized tribes as sovereign nations and our requirement for tribal consultation cannot be misconstrued.”

And while he said that the USDA “supports the bill,” he stressed in his verbal remarks that “we would like to work with the bill sponsors and the subcommittee to differentiate the work from our relationship with federally recognized tribes and land grant communities.”

Rep. Teresa Leger Fernandez (D-New Mexico) serves in a leadership role in the 117th Congress as Chair of the House Subcommittee for Indigenous Peoples of the United States. Photo courtesy House Committee on Natural Resources, Democrats

Rep. Teresa Leger Fernandez

Rep. Teresa Leger Fernandez (D-New Mexico) serves in a leadership role in the 117th Congress as Chair of the House Subcommittee for Indigenous Peoples of the United States. Photo courtesy House Committee on Natural Resources, Democrats

Rep. Teresa Leger Fernandez (D-New Mexico), the sponsor of H.R.5493, enthusiastically presented the bill

at the start of the hearing. Land grants represent an important part of her state’s history and culture, she said, noting that even her ancestors lived on

mercedes.

“New Mexicans have maintained that dedication to the land and living in the places they love,” said Leger Fernandez, who serves as chair of the

House Subcommittee for Indigenous Peoples of the United States.

“However, there’s also been this historic and constant struggle with the federal agencies that now have the forests and the grazing areas, and oftentimes even – you know — historic cemeteries are in these now federal lands,” said Leger Fernandez, who is in her first term in the U.S. Congress.

But after hearing Smith’s comments on behalf of the Biden administration, Leger Fernandez appeared to offer a concession — though not on the underlying premise of her legislation. She said she was willing to take another look at very nature of “consultation” in the bill, in response to the concerns about the trust and treaty relationship.

“I’m very open to getting specific language, you know codified in a sense, [of] what consultation means with regards to land grants,” Leger Fernandez said of her desire to keep working on the measure.

The USDA wasn’t the only federal agency standing up for the nation-to-nation framework at the hearing. Mark Lambrecht, the assistant director

for National Conservation Lands and Community Partnerships at the

Bureau of Land Management, also stressed the need to maintain the sanctity of tribal consultation policies.

“I would advise that formal consultation, government-to-government relationships is spelled out in the Constitution, federal statutes, executive orders,” Lambrecht responded when asked by Leger Fernandez, “and it differs from, I think, what this bill seeks to establish, which is written guidance for land managers to follow for early and regular communication between federal land management agency and the land grant-

mercedes.”

Like the USDA, Lambrecht insisted that the BLM already provides ways for land grant descendants to participate in federal management processes.

“That’s certainly something that we support — conversations about historical uses or other interests in the land grant-

mercedes and in federal land management,” Lambrecht said. “We also advise that this is something that we’re doing already. We have a liaison from the bureau that meets regularly with the New Mexico Land Grant Council and the land grant-

mercedes about some of these issues.”

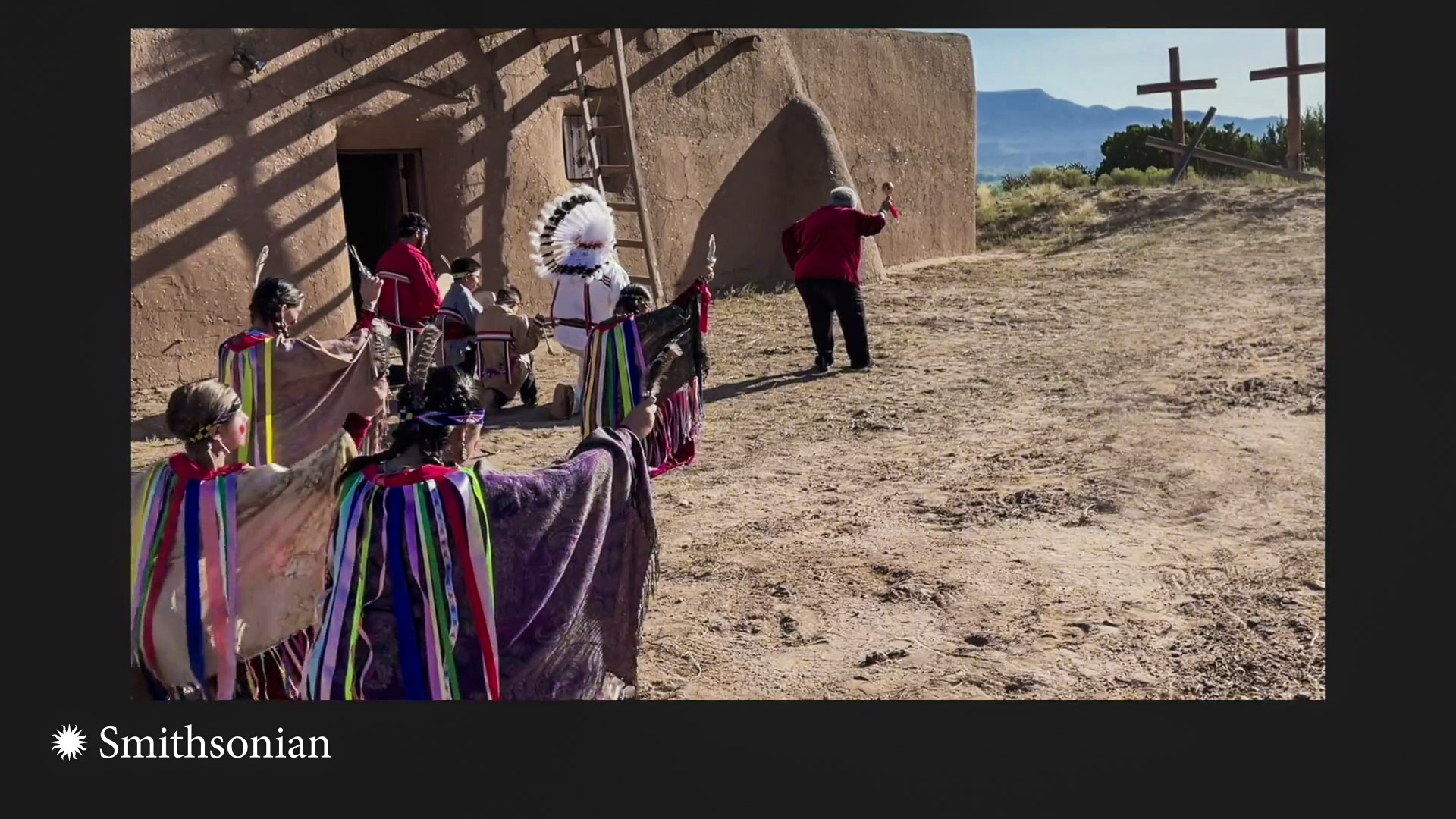

A church in Abiquiu, a community in northern New Mexico. Photo: Mary Madigan

A church in Abiquiu, a community in northern New Mexico. Photo: Mary Madigan

The

New Mexico Land Grant Council was formally established by the New Mexico Legislature in 2009 to address land grant issues in the state. The group’s manager, Arturo Archuleta, testified in support of H.R.5493 at the hearing, with his testimony on Tuesday showing how

mercedes are identifying themselves as having Indian heritage.

“Land grant-

merced communities were established between 1689 and 1854 through the granting of land from the Spanish Crown and the Mexican Government in what is now the United States’ Southwest,”

Archuleta said after opening his presentation with a brief greeting in the Spanish language.

“Our communities were settled and populated by our

mestizo and

genízaro ancestors,” Archuleta said, identifying modern-day descendants as people of mixed Indian heritage, as well as descendants of Indian people who were enslaved during the reign of the Spanish kingdom.

Archuleta further asserted a direct relationship between land grant heirs and Indian people, even though Indians, generally, weren’t entitled to the same rights as

mestizo or

genízaro residents during Spanish or Mexican rule in the Southwest. Mistreatment by the Spanish had led to the

Pueblo Revolt of 1680, an uprising organized by Pueblo tribes in present-day New Mexico and Arizona.

“Like our Native American cousins, accessing and protecting our traditional uses and associated natural resources on federal lands plays a critical role in ensuring the cultural integrity of our communities now and into the future,” Archuleta said.

Sen. Martin Heinrich (D-New Mexico), second from left, is seen at a 2015 meeting with members of the New Mexico Land Grant Council. Arturo Archuleta is on the far right. Photo: Sen. Heinrich

Sen. Martin Heinrich (D-New Mexico), second from left, is seen at a 2015 meeting with members of the New Mexico Land Grant Council. Arturo Archuleta is on the far right. Photo: Sen. Heinrich

The shift to an Indian, or mixed Indian, identity appears to be a relatively new development for the New Mexico Land Grant Council, which receives $221,900 in taxpayer funds annually

according to official reports. Just two years ago, when a prior version of the consultation bill was introduced in the House, the

group stated merely that land grants had been issued to communities that consisted of “Hispanic and Native American inhabitants.”

The

council’s own programs do not identify Indians, or mixed Indians for that matter, as beneficiaries. In fact, the

guidelines for the “Spanish & Mexican Community Land Grants-Mercedes Support Fund” make clear that only land grant heirs — and no other entities — can receive taxpayer money.

Under New Mexico law, the

mercedes are treated as political subdivisions of the state. In contrast, tribal nations exercise inherent sovereignty, independent of local, state or federal law.

Despite the subtle shift in language from the New Mexico Land Grant Council, some individual land grant descendants have been asserting various forms of Indian identity for longer periods of time, even

resorting to DNA tests to prove a

genetic relationship with their claimed ancestors. A common claim in this category is that of

genízaro, or a belief in

descent from Indian people who were enslaved during Spanish rule. Others equate

genízaro with people who were “detribalized” — or somehow lost their supposed “tribal” status.

In the case of the

modern-day community of Abiquiú, for instance, the land heirs say their ancestors were “officially granted under the Spanish Crown in 1754 as a

genízaro settlement (

genízaros were detribalized, Hispanicized Native Americans),” according to another

2020 letter in support of the consultation bill.

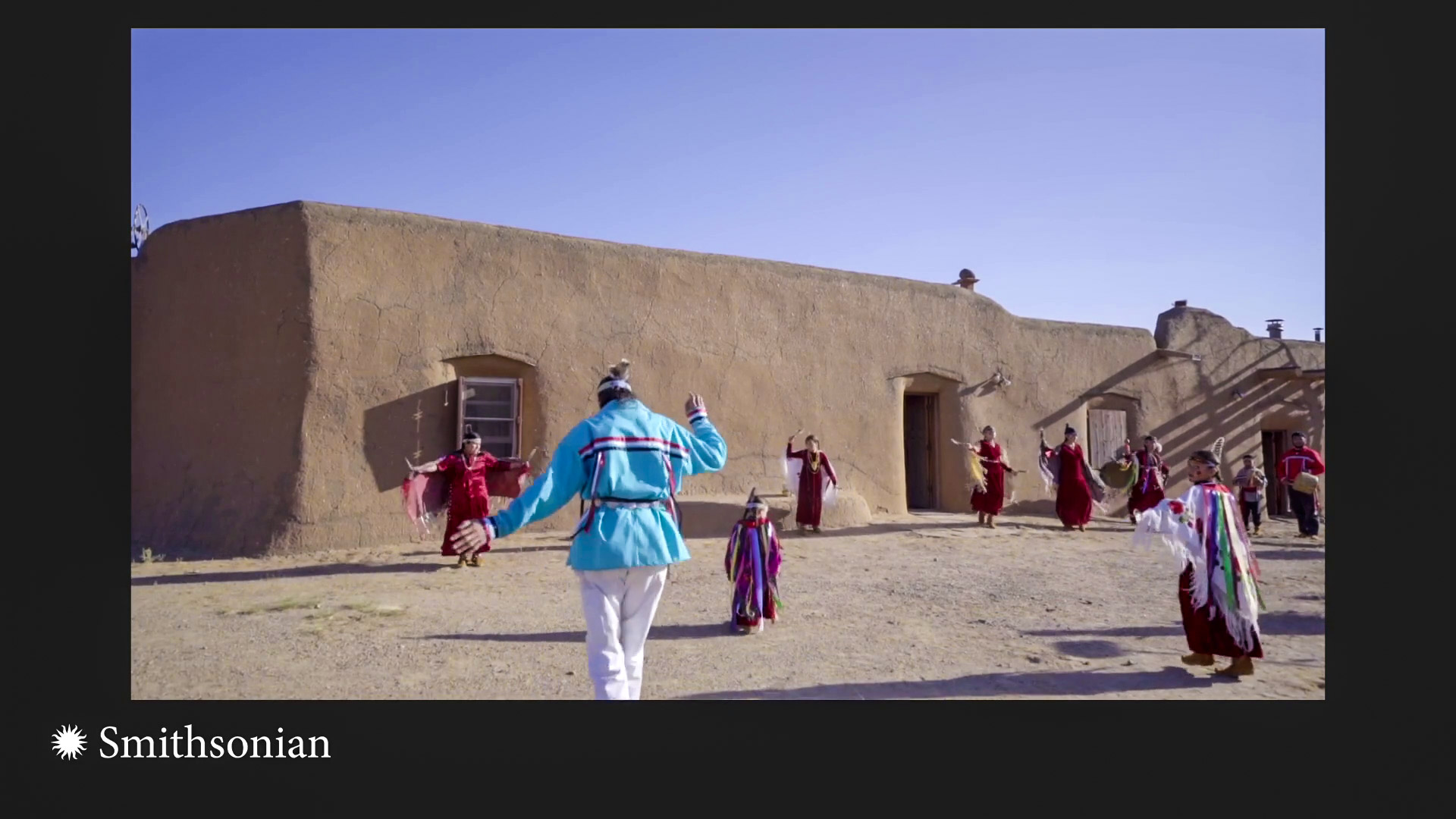

Las Inditas del Pueblo de Abiquiú

A group calling itself Las Inditas del Pueblo de Abiquiú — or “Native Indians of the Pueblo of Abiquiú — presented a series of performances as part of virtual symposium hosted by the National Museum of the American Indian in September 2021. The screenshots represent portions of the performance that was recorded in Abiquiú, New Mexico, for the “The Other Slavery” symposium.

New Mexico is home to

19 Pueblo tribes, the

Navajo Nation, the

Jicarilla Apache Nation and the

Mescalero Apache Tribe. The

Fort Sill Apache Tribe, whose ancestors were

taken as prisoners of war by the United States during the late 1800s, have since made a return to their ancestral lands after being removed to Oklahoma.

No Pueblo, Navajo or Apache leaders testified about H.R.5493 at the hearing on Tuesday, however. And no tribal leaders were on the witness list when an earlier version of the consultation bill was

taken up by the same subcommittee during the prior session of Congress.

The

earlier version of the consultation bill easily passed the

U.S. House of Representatives during the 116th Congress, after the chamber shifted to Democratic control for the first time in over a decade. The bill never made it through the

U.S. Senate, which was then under Republican rule. The latter chamber is now led by Democrats.

In addition to H.R.5493, another measure of interest was on the agenda on Tuesday. Only this one was more closely tied to affirming the nation-to-nation relationship.

A sign at the Berryessa Snow Mountain National Monument in California notes that the land is co-managed by the Department of the Interior and the Department of Agriculture. Photo: Samantha Storms / Bureau of Land Management

H.R.6366

A sign at the Berryessa Snow Mountain National Monument in California notes that the land is co-managed by the Department of the Interior and the Department of Agriculture. Photo: Samantha Storms / Bureau of Land Management

H.R.6366, the Berryessa Snow Mountain National Monument Expansion Act, would require the federal government to consult tribal governments before entering into co-stewardship agreements for the

Berryessa Snow Mountain National Monument in California. Chairman

Anthony Roberts of the

Yocha Dehe Wintun Nation testified in support of the measure.

“This co-stewardship provision is extremely important to us,” Roberts told lawmakers. “First of all, it requires the responsible federal agencies to complete a management plan for the monument. Although the monument was originally designated back in 2015, there is no monument management plan

currently in place.”

“Second, H.R. 6366 ensures that tribal knowledge, perspective, and practices will be part of the monument’s management going forward. That makes sense,” he continued. “After all, the area’s unique cultural resources and history were among the original reasons for its protection.”

“Third, the co-stewardship provisions of H.R.6366 represent an important opportunity for innovation while also remaining firmly grounded in federal law and policy,” Roberts concluded, underscoring the manner in which the bill upholds the trust obligations of the U.S.

https://www.twitter.com/CNPS/status/1497666571266711554

Lambrecht, the official from the BLM, said the Biden administration supports the bill, which adds about 3,900 acres of land already under federal control to Berryessa Snow. He also pointed out that an an area in the monument known as

Walker Ridge would be changed to

Molok Luyuk, which means “Condor Ridge” in the

Patwin language of the Yocha Dehe Wintun Nation.

“The administration recognizes and affirms that the United States’ trust and treaty obligations are an integral part of each department’s responsibilities for managing federal lands,” Lambrecht said in his written statement.

H.R.6366 is led by

Rep. John Garamendi (D-California).

House Subcommittee on National Parks, Forests, and Public Lands Notice

Legislative Hearing March 1, 2022