Indianz.Com > News > News21: COVID-19 pandemic exposes many challenges in Indian Country

COVID relief highlights complexity of issues facing Native Americans

Monday, August 30, 2021

News21

Congress allocated a historic amount of federal funds to tribes through the 2020 CARES Act and the 2021 American Rescue Plan Act. For some Indigenous communities, those federal funds were beneficial. For others, the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted deeper systemic complexities that federal funding cannot fully address.

Indigenous nations across the country have experienced chronic federal underfunding, which has led to disproportionate impacts tied to COVID-19 through housing, employment, public safety, food security, health care and economic outcomes.

In March 2020, the CARES Act established the Coronavirus Relief Fund, which allocated $8 billion to tribal governments and Alaska Native Corporations to address “necessary expenditures” incurred because of COVID-19.

A year later, American Rescue Plan Act funds allocated $31 billion for infrastructure needs and other federal programs for Indigenous communities.

Additionally, $1 billion is being divided and dispersed to each eligible tribal government, and $900 million was allocated for several purposes, including tribal housing improvements.

Congress also allocated funds to various Indigenous entities through smaller COVID-19 relief bills: $2.6 billion from the Consolidated Appropriations Act, no less than $750 million plus a share of no less than $11 million from the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act, and $74 million from the Families First Coronavirus Response Act.

“What we learned was, even though money was allocated, we were still running into a lot of issues,” said Eugenia Charles-Newton, a member of the Navajo Nation Council. “There were so many rules from the U.S. Department of Treasury regarding the CARES … that made it really difficult to try to spend that money where it was needed.”

‘They won’t help me’

The Blackfeet Nation received $38,692,273 in CARES money, according to Richard K. Delmar, acting inspector general for the Department of the Treasury.

But Marietta Green, a tribal elder who lives on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation near Browning, Montana, said she has been waiting for the tribal housing department to address her problems for years.

Green lives in a four-bedroom house where she raises three grandchildren. She said her home has high levels of mold, her plumbing is unpredictable and her lights get shut off about 11 a.m. when her electric bill isn’t paid on time.

The tribe used CARES Act funds to distribute $500 checks to enrolled members 18 or older. Green used her check to buy food and take care of her grandchildren.

Green said she covers the windows in the house’s back rooms to keep out the cold Montana winters, when temperatures can dip below zero. Many windows are broken or too drafty to keep the house warm, she said.

“The housing authority, they’re supposed to be the authority,” Green said. “They’re supposed to be there for us, they’re supposed to be helping us maintain these places and giving us equipment so we could maintain these places. … But they won’t help me.”

Green said when she moved in about 25 years ago, the housing department helped with rental assistance, but that stopped. Green applied for rent and water assistance through the tribe and has been told by the housing department her one-time assistance check is on the way.

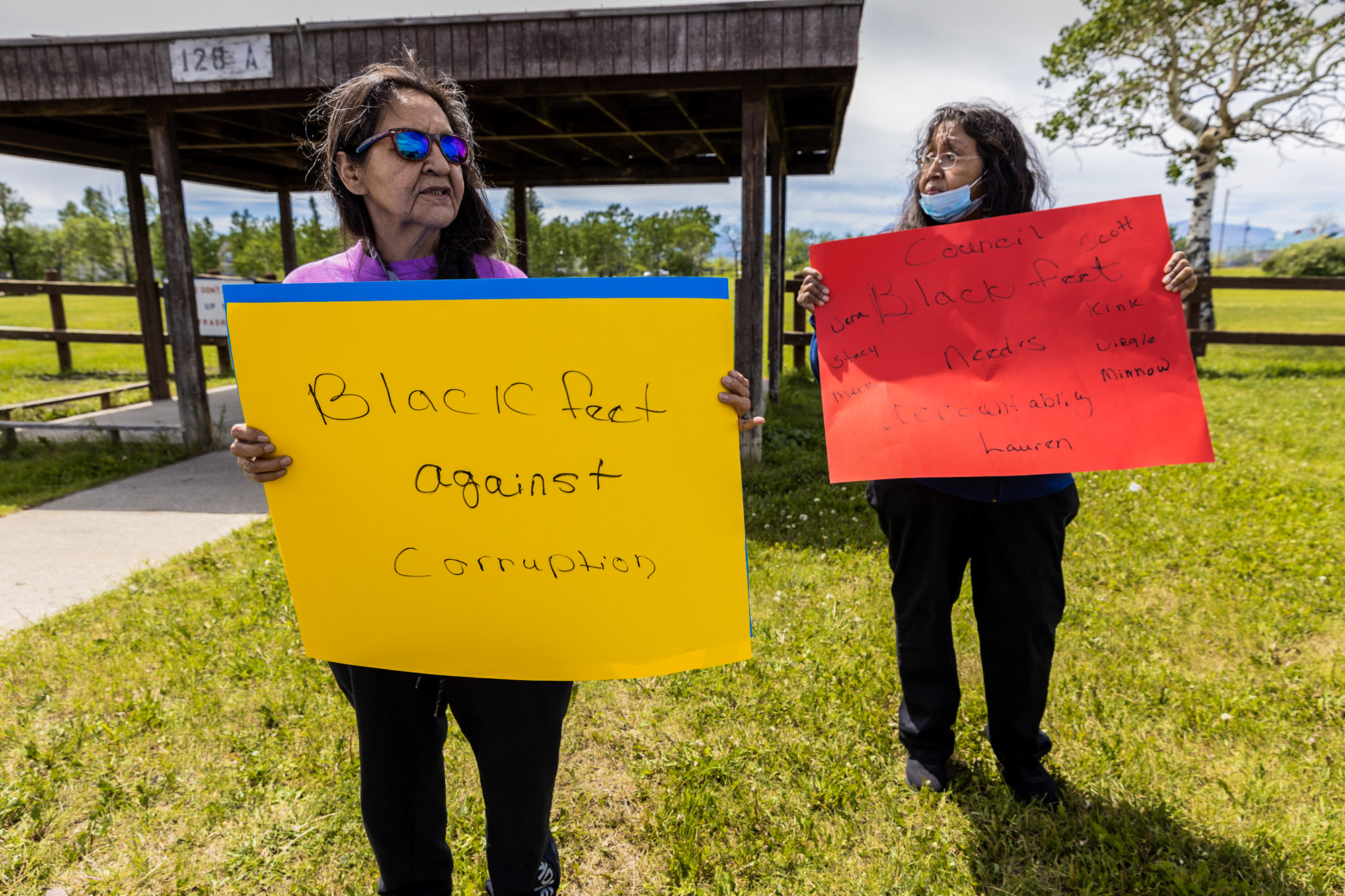

Tribal members like Green said they are troubled by the lack of transparency from their government on how CARES Act funding was spent. On June 21, 2021, Green and fellow tribal members Laura Smith and Leona Gopher protested for accountability outside the Blackfeet Tribal Business Council office in Browning.

‘You have to report on us’

Health disparities affect Native Americans in urban settings as well. Roughly 70% of Native Americans reside in urban areas, according to the Department of Health and Human Services, but most Indian Health Services funding is directed to tribal health facilities.

IHS received more than $1 billion in CARES Act funds. Of the $600 million immediately distributed in April 2020, $570 million went to IHS and tribal health facilities, while only $30 million went toward the 41 health programs in the Urban Indian Organizations.

Being able to provide specialized care for Indigenous people who live off-reservation is the obligation of the federal government, according to Kerry Lessard, executive director of Native American LifeLines, an IHS-contracted referral service.

“A person’s tribal citizenship doesn’t change just because their address does, and so any trust in treaty responsibilities the federal government has to tribal citizens doesn’t stop just because they leave the reservation,” Lessard said.

According to Wendy Carrión, director of health services at the Sacramento Native Health Center, roughly 46% of their patients have multiple preexisting conditions, making them vulnerable to severe effects from COVID-19.

Carrión said the urban health program found its patients wanted information and care from officials who understood the needs of Indigenous people. It was also important, she said, to provide not only Sacramento’s Indigenous populations with vaccines, but other races and ethnicities as well in order to protect the Native American community.

“We needed to focus on the Native community and make sure that … they have access to both testing and immunization,” Carrión said. “But in order to keep the community safe … we were able to talk to them and be able to expand it to the rest of the community.”

Also impacting the response to the pandemic is data collection and funding, according to Dr. Spero Manson, an epidemiologist and director of the Colorado School of Public Health’s Centers for American Indian & Alaska Native Health.

Maryland, for example, isn’t tracking COVID-19 cases among Native Americans.

“If we are to understand the health status of the Native community and to make sure that interventions and funding are being what they need to be, you have to report on us,” said Lessard. “But more than that, it is figuratively and literally saying you don’t count — we’re not counting you, you don’t count.”

‘COVID-19 was an eye-opener’

Some tribes have used federal funds to address underlying issues exacerbated by the pandemic. In addition to distributing COVID-19 relief checks to members, installing broadband infrastructure and building an emergency response center, the Yurok Tribe used CARES Act funds to address ongoing food security issues on the reservation.

The Yurok Reservation is nestled along a stretch of the Klamath River in Northern California. The tribe, which has more than 5,000 members, was declared a food desert by the Department of Agriculture in 2017. The pandemic, as well as other crises in the last several years, has made tribal members aware of the ongoing food insecurity in the area.

Forty acres of grassy meadows, daisy-covered hills, towering redwoods and huckleberry brush are becoming “food villages,” which will comprise gardens, a commercial kitchen and tiny homes. This land — the ancestral land of the Yurok people – was purchased with the tribe’s CARES Act allotment for $490,000, according to property tax records.

Walking along this land, Taylor Thompson, manager of the tribe’s food sovereignty division, established in August 2020, said having a sustainable food source was important in case of a crisis.

“What can we do to make sure that we are able to sustain ourselves in case of a large-scale catastrophe?” Thompson asked. “COVID-19 was kind of an eye-opener that sometimes larger systems go down. So what can we do to make sure that we can help support our people through those tough times?”

‘We don’t have that infrastructure’

On the Navajo Nation, there have been more than 31,000 cases of COVID-19 and more than 1,300 deaths. According to the 2020 census, 172,813 people live on the reservation, most of them Navajo. At times throughout the pandemic, tribe has used daily curfews, lockdowns and mask mandates to curb the spread of COVID-19.

The Navajo Nation received $714,189,631 in CARES Act funding from the U.S. government – a 225% increase in funds from what the nation normally receives. As $1.86 billion in first-round American Rescue Plan Act funds rolls into the Navajo government’s coffers, tribal officials are deciding how to distribute this new financial opportunity.

According to Navajo Police Chief Phillip Francisco, his department requested $36 million in resources from the CARES Act and received only hazard pay and personal protective equipment. He said he’s hopeful this round of American Rescue Plan Act funding will address long-running infrastructural deficiencies and provide an opportunity for the department’s “renaissance.”

With about 200 commissioned personnel, the department is stretched thin from answering hours-long calls on rural dirt roads — often to homes so remote they don’t have addresses, with radios whose signals don’t cover remote service areas.

‘The effects still linger’

The CARES Act and American Rescue Plan Act brought unprecedented levels of funding to Indigenous communities across the U.S., allowing some to address ongoing infrastructure issues exacerbated by COVID-19, including food security, water access and emergency response.

Sen. Brian Schatz, D-Hawaii, Senate Indian Affairs Committee chair, said more investment from the federal government is needed for long-term improvements of infrastructure in Indigenous communities.

“It is a shame that it took a global pandemic for us to recognize how these unmet needs put Native communities behind the eight-ball when it comes to health care and economic recovery,” Schatz said at a roundtable meeting in June. “As Congress acted to address both, it became clear that federal investment in building new and updating existing infrastructure in Native communities was no longer ‘nice to have’ but actually essential.”

For Richard Horn of the Blackfeet Nation, efforts toward bolstering essential infrastructure continue while his tribe is recovering from the long-term implications of COVID-19. The trauma members of his tribe experienced from the pandemic, he said, will leave a lasting impression. “It was a whole new learning curve and very traumatic,” Horn said. “We had to relearn and rethink all of the things that made us close. We had to step away from it. And among the people in my community, the effects still linger.” This report is part Unmasking America, a project produced by the Carnegie-Knight News21 initiative, a national investigative reporting project by top college journalism students and recent graduates from across the country. It is headquartered at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University. For more stories, visit unmaskingamerica.news21.com. For more stories from Cronkite News, visit cronkitenews.azpbs.org.Concurrent crises, including the coronavirus, have worsened food insecurity within the Yurok Tribe, spurring some to explore their own solutions. #FoodSovereignty #Coronavirus #COVID19 #California #News21 https://t.co/r7szlBVueE

— indianz.com (@indianz) August 9, 2021

Note: This story originally appeared on Cronkite News. It is published via a Creative Commons license. Cronkite News is produced by the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University.

Search

Filed Under

Tags

More Headlines

‘Mr. Secretary, Why are you silent?’: Interior Department cuts impact Indian Country

VIDEO: Oversight Hearing to Examine Native Communities’ Priorities for the 119th Congress

AUDIO: Oversight Hearing to Examine Native Communities’ Priorities for the 119th Congress

AUDIO: Leaving Indian Children Behind: Reviewing the State of BIE Schools

Cronkite News: Native student program shuts down due to President Trump

NAFOA: 5 Things You Need to Know this Week (March 3, 2025)

Filmmaker Julian Brave NoiseCat makes history at Academy Award ceremony

Senate Committee on Indian Affairs schedules business meeting to consider bills

Chuck Hoskin: Cherokee Nation advocates for Indian Country

Native America Calling: Native education advocates assess the new political landscape

AUDIO: American Indian and Alaska Native Public Witness Hearing Day 3

Native America Calling: The Trump administration, endangered fish and a new book

AUDIO: American Indian and Alaska Native Public Witness Hearing Day 2, Afternoon Session

AUDIO: American Indian and Alaska Native Public Witness Hearing Day 2, Morning Session

Native America Calling: The game is changing for student athletes

More Headlines

VIDEO: Oversight Hearing to Examine Native Communities’ Priorities for the 119th Congress

AUDIO: Oversight Hearing to Examine Native Communities’ Priorities for the 119th Congress

AUDIO: Leaving Indian Children Behind: Reviewing the State of BIE Schools

Cronkite News: Native student program shuts down due to President Trump

NAFOA: 5 Things You Need to Know this Week (March 3, 2025)

Filmmaker Julian Brave NoiseCat makes history at Academy Award ceremony

Senate Committee on Indian Affairs schedules business meeting to consider bills

Chuck Hoskin: Cherokee Nation advocates for Indian Country

Native America Calling: Native education advocates assess the new political landscape

AUDIO: American Indian and Alaska Native Public Witness Hearing Day 3

Native America Calling: The Trump administration, endangered fish and a new book

AUDIO: American Indian and Alaska Native Public Witness Hearing Day 2, Afternoon Session

AUDIO: American Indian and Alaska Native Public Witness Hearing Day 2, Morning Session

Native America Calling: The game is changing for student athletes

More Headlines