Indianz.Com > News > Albert Bender: Report examines genocide at Indian boarding schools

Indian boarding schools report details horror of Indigenous dispossession and genocide in U.S.

Monday, July 11, 2022

People's World

The recent Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report has garnered mixed responses, ranging from being characterized as “monumental” to being said to “leave key questions unanswered.” I would agree with both assessments, but would not fault the report with criticism.

It indeed is “monumental” in that it is the first report of its kind in which the U.S. government admits responsibility for the 150-plus years of atrocities committed against Indigenous children in its boarding school “hellholes.” On the other hand, there remain key unaddressed issues, but this is just volume one of the investigation’s findings, and subsequent reporting may provide more answers.

The sheer quantity of the work involved with producing the report was enormous; the research involved reviewing 98.4 million sheets of paper on Federal Indian boarding schools—records, testimony, and other documents.

The U.S. goal: Indigenous dispossession

Most eye-opening in the report is the admission that the boarding school system was directly aimed at taking Indian land, by an insidious, perfidious scheme that used so-called “education” as a cover. It was a prime vehicle for the dispossession of Native people, within the framework of settler colonialism. The main goal of the boarding school system was separating Indigenous people from Indigenous land. This is supported by an opening statement of the Initiative, given by Newland, which reads as follows:

“This report places the Federal boarding school system in its historical context, explaining that the United States established this system as part of a broader objective to dispossess Indian Tribes, Alaska Native Villages, and the Native Hawaiian Community of their territories to support the expansion of the United States.”

This is a profound statement and lays the groundwork for the rest of the report. The overall goal of the boarding school system was to take Indian land by assimilation (cultural genocide), on the one hand, and the outright genocide (physical erasure) of Indigenous children on the other.

Further cited in the Initiative’s report, in regard to Indian territorial dispossession, is the Kennedy Report of 1969, which held that Federal Indian boarding schools “were designed to separate a child from his reservation and family, strip him of his tribal lore and mores, force the complete abandonment of his native language, and prepare him for never again returning to his people.”

The forcible assimilation—i.e. cultural genocide—implied the eventual absorption of the Native population into the non-Indian population. And with physical genocide, the Native population would be physically erased over time. Hence, the boarding system was a double-edged sword of genocide.

This system was seen by the U.S. government as a means for taking of Indigenous homelands. The cultural and physical genocide of Native children was directed at generations of Native Americans who would either be assimilated or decimated. Hence, the goal of dispossession would be realized.

Starvation as a weapon

Another point brought out in the Initiative’s report, but perhaps not so well known among the broader population in the U.S., was the practice of withholding food rations from families who would not submit their children to be carried off to the heinous schools. This writer was aware of this abominable practice but only became aware that this genocidal measure was actually enacted into law thanks to the report.

Shockingly, by the Act of March 3, 1893, Congress authorized the Secretary of the Interior to withhold rations, which were guaranteed by treaties, from Native families whose children did not attend the schools. An organization of white church leaders, social reformers, and government officials—the misnamed Friends of the Indian, formed in 1883—provided cover for the policy, stating that starvation was a proper punishment for Native families who refused to recognize “what was good for them.”

Families were threatened with starvation or starved into submission once dependency on government-supplied food was established on the reservations. This was inhuman, using starvation as a weapon to procure children. The U.S. government must be held accountable for its crimes.

Intergenerational health legacy of the schools

Also not widely known, but addressed in the findings, is the intergenerational long-term health effects on the families of boarding school survivors. Indigenous childhood school experiences fostered negative health impacts on adults who had been boarding school attendees. Studies show that American Indians who attended boarding schools have lower physical health levels than non-attendees.

Indigenous boarding school children had a 44% greater count of past-year chronic physical health problems (PYCPHP) when reaching adulthood than adult non-attendees. Adults who were attendees were more likely to have cancer (more than three times), tuberculosis (more than twice), and were also more likely to have high cholesterol, diabetes, anemia, and gall bladder disease than non-attendee adults. Other research indicated that now-adult attendees experience increased risk of PTSD, depression, and unresolved grief.

The further result, according to descriptions from survivors, was a “prevailing sense of despair, loneliness, and isolation from family and community.” The report asserts that stressors from boarding school experience can produce “epigenetic alterations” that are then transferred to the children of attendees, a process known as “epigenetic inheritance.” The trauma, then, became an inheritance passed down through generations.

The report also references the Running Bear studies of 2019, funded by the National Institute of Health, authored by Dr. Ursula Running Bear, et al., entitled “Boarding School Attendance Response and Physical Health Status of Northern Plains Tribes,” which reinforce the assertion that Federal Indian boarding school policies “often impacted several generations, “leading to an intergenerational pattern of cultural and familial disruption under the direct and at times indirect support by the U.S. government of Federal and non-Federal entities.”

This research was the first medical study to systematically and quantitatively prove that the Federal Indian boarding school system continues to negatively affect the health of adult boarding school survivors and their descendants.

Boarding schools in historical context

Genocide as a concept has developed and evolved over the decades and must be updated and analyzed to concretely apply it to what happened over a century and a half in the Indian boarding schools at the hands of successive U.S. settler colonialist regimes of the 19th and 20th centuries.

The U.S. boarding school system meets the definition of genocide established by the United Nations General Assembly’s Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. Article II of the Convention reads as follows:

“In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group, as such: (a) Killing members of the group; (b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; (c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; (d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; (e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”Throughout the short tenure of the United States on the stage of world history, all of the above prohibited five acts have been utilized by the federal government against the Indigenous peoples of this land. Section (e) of Article II directly applies to the Indian boarding schools—the forcible transferring of the children of one group, Indigenous Americans, to another group, white Americans. This involves by definition, not necessarily physical or biological destruction (although there was physical destruction in the boarding schools, judging by the huge numbers of Native children who perished), but rather the destruction of the group as a cultural and social unit. This typically occurs when children of the protected, victimized group are transferred to the perpetrator group. In the boarding school case, the goal of the U.S. was to “de-Indianize” the children and make them into carbon copies of white America, in effect a transferal to the perpetrator group. It amounted to the destruction of Native Americans as a distinct cultural and social entity. The children were given European names. The intent was to strip them of their culture, use them for manual labor, and transform them into “brown-skinned white folks,” at least the ones who survived the excruciating gauntlet of the horrendous boarding schools.

Hitler’s inspiration

In conclusion, it is relatively well known that Adolf Hitler was inspired in his genocide of the Jewish people by the U.S. genocide of Native Americans. Hitler was very familiar with the abominable conditions imposed on Indigenous people by the U.S. settler colonialist state.

He praised the way that “Aryan” America had conquered “its own continent” by clearing the land of “natives” and remarked approvingly of how the United States had “gunned down the millions” of Indians to a “few hundred thousand, and now keep the modest remnant under observation in a cage.”

Hitler envisioned Nazi Germany as a settler colonialist state expanding eastward in the same vein as the United States had expanded west.

Albert Bender is a Cherokee activist, historian, political columnist, and freelance reporter for Native and Non-Native publications. He is currently writing a legal treatise on Native American sovereignty and working on a book on the war crimes committed by the U.S. against the Maya people in the Guatemalan civil war He is a consulting attorney on Indigenous sovereignty, land restoration, and Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) issues and a former staff attorney with Legal Services of Eastern Oklahoma (LSEO) in Muskogee, Oklahoma.

This article originally appeared on People's World. It is published under a Creative Commons license.

Related Stories

Arne Vainio: We all have an opportunity to redeem (August 12, 2021)Native America Calling: Welcoming home children who died at Carlisle Indian School (July 29, 2021)

Rosebud Sioux Tribe hosts funeral services Indian boarding school students (July 19, 2021)

Photos: Lakota children spend final morning away from homelands (July 19, 2021)

Lakota youth return home after more than a century away at Indian boarding school (July 19, 2021)

Rosebud Sioux Tribe hosts prayer services in South Dakota for return of Indian boarding school students (July 16, 2021)

Rosebud Sioux Tribe hosts prayer services in Iowa for return of Indian boarding school students (July 16, 2021)

‘We are bringing them home’: Lakota youth on long overdue journey from Indian boarding school (July 15, 2021)

Cronkite News: Indian boarding school era under investigation (July 8, 2021)

City pledges action to honor lives lost at Indian boarding school (July 1, 2021)

Chuck Hoskin: Cherokee Nation acquires boarding school site (June 30, 2021)

National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition supports federal review of Indian boarding school era (June 25, 2021)

Navajo Nation hails federal investigation into Indian boarding school era (June 23, 2021)

National Congress of American Indians welcomes boarding school initiative (June 23, 2021)

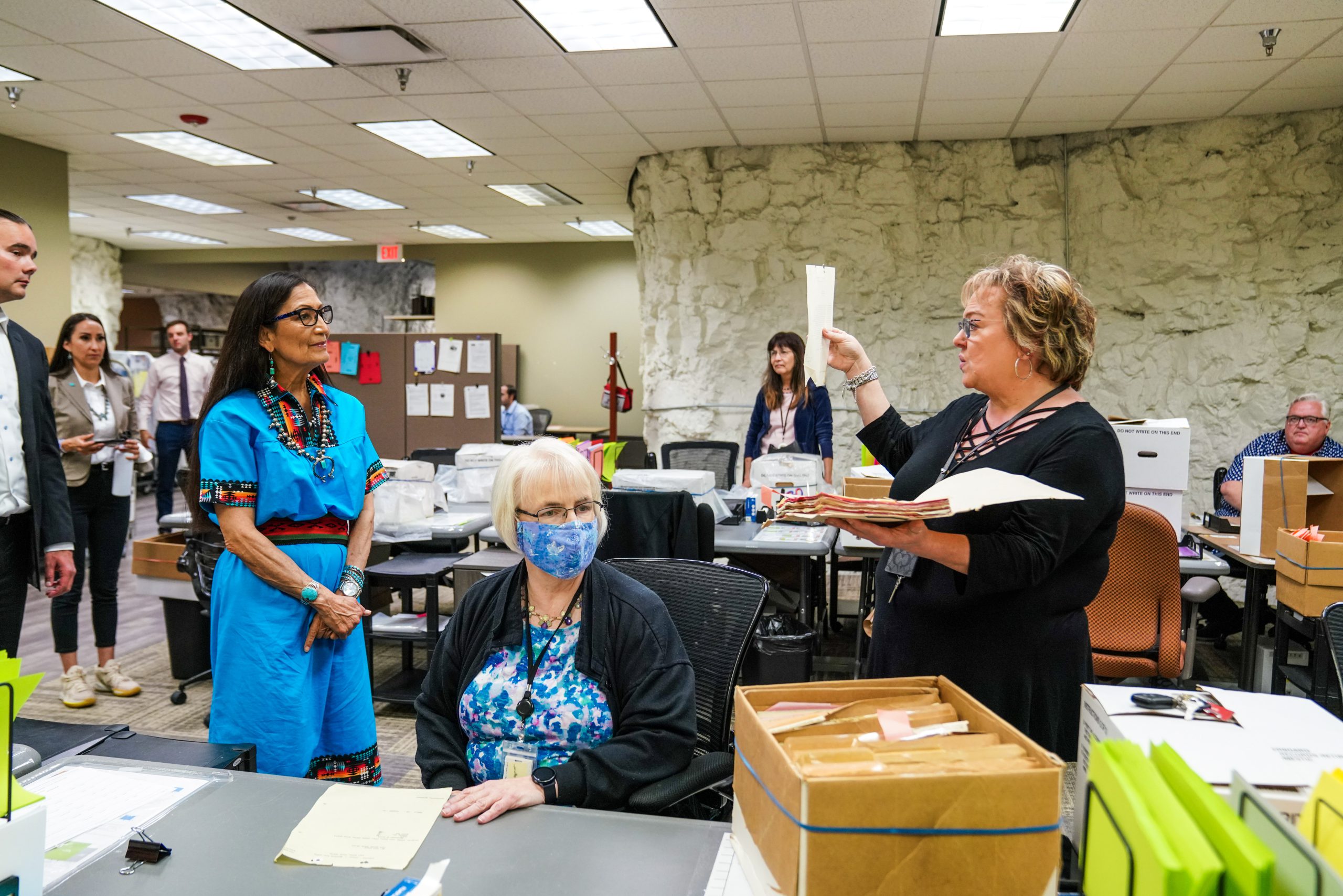

Secretary Deb Haaland: Federal Indian Boarding School Truth Initiative (June 22, 2021)

‘Our communities are still mourning’: Secretary Haaland announces federal Indian boarding school initiative (June 22, 2021)

‘I know that this process will be painful’: Secretary Haaland announces Indian boarding school review (June 22, 2021)

Secretary Haaland addresses National Congress of American Indians (June 22, 2021)

Search

Filed Under

Tags

More Headlines

Chuck Hoskin: Cherokee Nation celebrates Cherokee women

Native America Calling: Tribal rights, a new restaurant and more are on The Menu

Native America Calling: Tribes vie for better access to traditional plants

Senate committee schedules confirmation hearing for Interior nominee

Fact Sheet: Department of Health and Human Services to undergo ‘dramatic restructuring’

Press Release: Department of Health and Human Services to undergo ‘dramatic restructuring’

Native America Calling: The new Social Security reality for Native elders

Montana Free Press: Hip-hop artist Foreshadow celebrates latest release

Cronkite News: Bill creates alert system for missing and murdered relatives

Bureau of Indian Affairs approves HEARTH Act regulations for Mohegan Tribe

House Subcommittee on Indian and Insular Affairs sets field hearing for self-determination anniversary

Native America Calling: Sometimes, COVID doesn’t go away

Native America Calling: The changing landscape for subsistence hunting and fishing

Press Release: AIHEC ‘deeply concerned’ about closure of Department of Education

Press Release: Oklahoma Indian Gaming Association weighs in on sports betting legislation

More Headlines

Native America Calling: Tribal rights, a new restaurant and more are on The Menu

Native America Calling: Tribes vie for better access to traditional plants

Senate committee schedules confirmation hearing for Interior nominee

Fact Sheet: Department of Health and Human Services to undergo ‘dramatic restructuring’

Press Release: Department of Health and Human Services to undergo ‘dramatic restructuring’

Native America Calling: The new Social Security reality for Native elders

Montana Free Press: Hip-hop artist Foreshadow celebrates latest release

Cronkite News: Bill creates alert system for missing and murdered relatives

Bureau of Indian Affairs approves HEARTH Act regulations for Mohegan Tribe

House Subcommittee on Indian and Insular Affairs sets field hearing for self-determination anniversary

Native America Calling: Sometimes, COVID doesn’t go away

Native America Calling: The changing landscape for subsistence hunting and fishing

Press Release: AIHEC ‘deeply concerned’ about closure of Department of Education

Press Release: Oklahoma Indian Gaming Association weighs in on sports betting legislation

More Headlines