Indianz.Com > News > Albert Bender: Truth, justice, and reconciliation for Indian boarding schools

Thousands of Indigenous children perished in ‘genocide boarding schools’

Friday, August 13, 2021

People's World

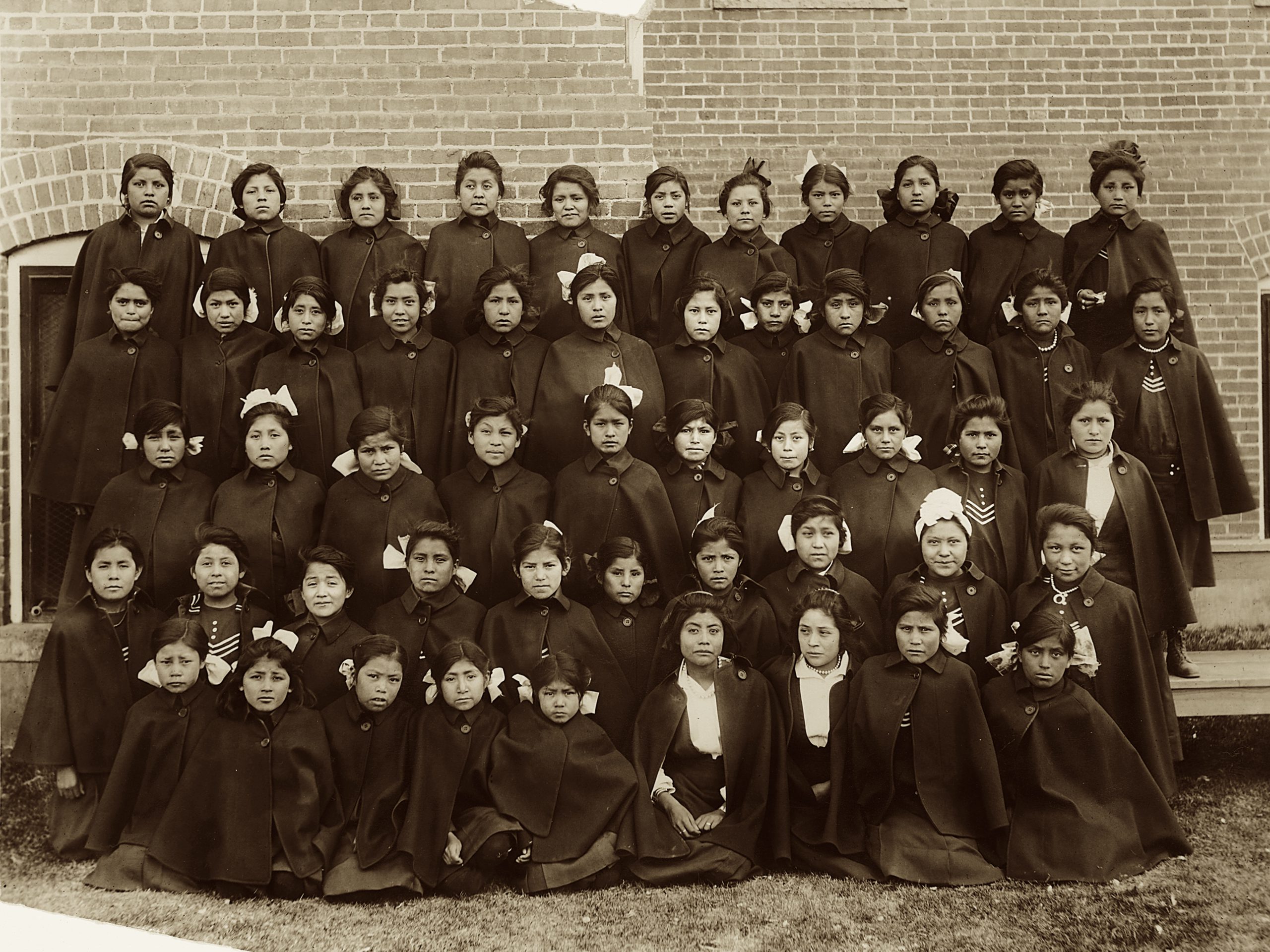

Hunger. Starvation. Beatings. Ill-clothed in the cold of winter. Forbidden to speak their Native tongues. Sexual predators roaming the dormitory halls in the middle of the night like wild animals searching for prey and snatching youngsters from their beds. Such was the lot of thousands of Indigenous children in the heyday of the Indian boarding school era which stretched from the 1870s to the 1960s in the United States and Canada.

The finding of almost 2,000 unmarked graves so far at former residential school sites in Canada is just the tip of the iceberg for the thousands more surely to be located in that country and in similar searches in the United States. Some of the graves found in Canada were of children as young as 3-years-old.

U.S. capitalism, in its drive to exploit the natural resources of the country, conducted bloody wars of extermination against the land’s Indigenous peoples, and in the late 19th century, it continued the genocide by the elimination of Indigenous children, culturally and literally. Canada rapidly and assiduously followed suit.

In May, a total of over 1,400 unmarked graves were found at the sites of four former Indian residential schools by Canadian First Nations conducting ground penetrating radar searches. These residential schools were government-sponsored religious institutions ostensibly created for the forced assimilation of Native children into white society. The discovery of the graves reverberated across the globe. Canada had been pursuing a truth and reconciliation process since 2007, at the behest of the First Nations, and the finding of the unmarked graves of children is one result of the process.

Canadian discoveries prompting U.S. searches

Prompted by the finding of hundreds of unmarked graves in Canada by Indigenous nations, Native American Cabinet Secretary Deb Haaland on June 22 took the unprecedented but much celebrated step of authorizing a Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative to determine if there are similar gruesome and tragic discoveries to be made in the U.S. The likelihood of such findings in this country is more than probable, as the U.S. Indian Boarding School system was much more extensive than the Canadian model. The report on the Initiative is due on April 1, 2022.

In Canada, the Indian Residential Schools from their beginnings were institutions overrun with sexual predators preying on the children. Reportedly, the Canadian students were kept constantly hungry and beaten into obedience, an arrangement which provided a fertile field for more abuse. Of the 150,000 Native children taken to these hellholes, a horrifyingly and shockingly huge proportion were the victims of rape and molestation by principals, teachers, dormitory supervisors, and even maintenance workers and janitors. This was monstrous.

In many schools, an astonishing 70% of students might have been subjected to sexual abuse. Incredibly and disgracefully, few of the system’s predators have been doled out even token punishments for terrorizing generations of Native children. Those who are still alive must be apprehended and punished in the same way Nazi concentration camp guards and killers are hunted down and punished.

History of the U.S. Indian Boarding School system

Beginning in 1819, with passage of the Indian Civilization Act, the U.S. ostensibly promoted the so-called “civilization” of American Indians by the creation of boarding schools that sanctioned the wholesale abduction—the kidnapping—of children from their families. In the latter years of the 19th century, U.S. soldiers were sent to abduct the children, and many were removed in handcuffs.

The best known of these institutions was Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. Between 1879 and 1918, over 10,000 children from 140 nations attended Carlisle. Of this number, over 1,800 children ran away from the institution, and nearly 500 died during its existence. The school was founded by Gen. Richard Pratt in 1979, just three years after Custer’s annihilation by Native forces at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in June 1876. This would seem to be no coincidence. In 1885, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs Hiram Price said, “It is cheaper to give them education than to fight them.”

Indian Boarding Schools were an anomaly in world history

Nowhere else in the history of humanity has the wholesale abduction, kidnapping, and imprisonment of the children of a people who are taken thousands of miles from home and held in these veritable prisons, subjected to sexual atrocities, and physical abuse, found other than in Canada and the United States.

Further, this was done, hypocritically, under the guise of education. This was done to diffuse a sense of hopelessness and helplessness throughout Indigenous communities. The children were held as hostages. This was done to impress upon Native people the utter power, cruelty, and ruthlessness of the capitalist governments. That which is most precious to any people are its children, and to have them summarily taken away was another racist attempt to extinguish an entire people. This type of genocide has happened to no other people on the face of the earth.

But the survival of the Indigenous in Canada and the U.S. bespoke of the tremendous resilience and strength of Native parents and the children who survived in the face of some of the most horrific oppression in the annals of humanity. Nowhere else in history has the wholesale abduction of the progeny of an oppressed people been witnessed.

The schools were replete with sexual, physical, and cultural abuse. Their legacy is one of intergenerational trauma extant to this very day. In some schools, no crying or laughing was allowed. The granddaughter of one boarding school survivor recalls her grandmother recounting that she was always hungry and always cold. Another survivor recalls fellow schoolmates being taken out of their dormitory beds in the middle of the night and never seen again. In the Canadian model, the schools were replete with sexual molestation of both boys and girls. Stories abound of young Native girls giving birth to babies that were thrown into incinerators.

Both the Canadian and U.S. institutions were schools of genocide. In fact, the motto of the Carlisle School was “Kill the Indian, save the man.” Various shameful practices were used to procure children for these genocide schools, the most vexing being the cutoff of rations to reservation families until the children were produced to be sent away.

In reference to the church-run schools, there was a widespread belief in Euro-American society that if Indians could be converted to Christianity, they would no longer fight being dispossessed of their land. It was thought Indians would look to salvation in an afterlife—“the pie in the sky”—and not be concerned with earthly oppression.

I am grateful to have participated in a U.S. Army ceremony today with the Rosebud and Ogala Sioux Tribes to return the children who died at the Carlisle Indian School. I am committed to elevating this tragic history so that we can build a better future for our children. pic.twitter.com/O5GCARkOX7

— Secretary Deb Haaland (@SecDebHaaland) July 14, 2021

The call for justice must continue

This column, along with countless others, is just the beginning of the monumental process of finding out what happened in the U.S, to thousands upon thousands of children in the hellish throes of these institutions of medieval horror. There needs to be truth, justice, and reconciliation—with the emphasis first on truth and justice. Punishment must be heavily meted out to all guilty parties. This is just the beginning, as the Native communities will appropriately deal with what must be done. There can be no healing or reconciliation without first truth and justice or a parallel path to healing and reconciliation.

As this journey into the inner sanctums of historic tragedy continues, there will be discoveries made that will shock the conscience which shall be duly reported. In the U.S., there has never been an official count of how many students died in what has been described by one survivor as “hell schools.”

What happened at these repositories of terror were gross human rights violations that could arguably be subsequently brought before the United Nations. (Furthermore, the abduction and abuse of Indigenous children continued well into the 20th century bringing about the passage of the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA). Moreover, this was carried into the 21st century with the abduction of Native children by the state of South Dakota).

What is inspiring and worthy of endless praise is that these courageous children who survived, not only survived, but left their homes as INDIANS and returned as still INDIANS. As Deb Haaland said recently, “Clearly, the cultural genocide part didn’t work, because we’re still here.” Their incomparable heroism can never be forgotten and is a source of constant pride in the face of what they endured—the most adverse racist circumstances and perversion. They came home wounded and battle scarred, but still Indigenous. They returned, as my grandmother said, not as “brown-skinned white folks.”

Moreover, those who never returned home must never be forgotten and must be forever honored.

“The whole residential school system was meant to destroy an entire people,” a Native American advocate said recently. But the heroic resistance of the children, even while in captivity, stopped the assimilation process. The culture and people live on.

But what also can never be forgotten is the quest for justice, the quest for punishment responsibility, and accountability for the unspeakable atrocities that took place within the walls of these institutions of horror.

This article originally appeared on People's

World. It is published under a Creative

Commons license.

Albert Bender is a Cherokee activist, historian, political columnist, and freelance reporter for Native and Non-Native publications. He was an organizer and delegate to the First and Second Intercontinental Indian Conferences held in Quito, Ecuador and Quetzaltenango, Guatemala. Recently, he has been an active participant and reporter in the Standing Rock struggle in North Dakota. He is an attorney and is currently writing a legal treatise on Native American sovereignty. He is also writing a book on the war crimes committed by the U.S. against the Maya people in the Guatemalan civil war of the late 20th century. He is also the recipient of several Eagle Awards by the Tennessee Native American Eagle Organization and a former Director of Native American Legal Departments and a Tribal Public Defender.

Search

Filed Under

Tags

More Headlines

Native America Calling: Mental health experts point to personal connections to maintain winter mental health

Native America Calling: Tribes ponder blood quantum alternative

Defense bill snubs Indian Country in favor of Lumbee federal recognition

NAFOA: 5 Things You Need to Know this Week (December 8, 2025)

Chuck Hoskin: Cherokee Nation benefits from extension of health care credits

Native America Calling: Tribal museums reflect on tumultuous year, chart their next steps

Press Release: National Museum of the American Indian hosts Native art market

AUDIO: Sea Lion Predation in the Pacific Northwest

Native America Calling: Tribal colleges see an uncertain federal funding road ahead

Native America Calling: Short films taking on big stories

Native America Calling: Advocates push back against new obstacles to Missing and Murdered Indigenous Relatives momentum

Native America Calling: For all its promise, AI is a potential threat to culture

NAFOA: 5 Things You Need to Know this Week (November 24, 2025)

Chuck Hoskin: Cherokee Nation invests in rural transportation

Native America Calling: Native candidates make strides in local elections

More Headlines

Native America Calling: Tribes ponder blood quantum alternative

Defense bill snubs Indian Country in favor of Lumbee federal recognition

NAFOA: 5 Things You Need to Know this Week (December 8, 2025)

Chuck Hoskin: Cherokee Nation benefits from extension of health care credits

Native America Calling: Tribal museums reflect on tumultuous year, chart their next steps

Press Release: National Museum of the American Indian hosts Native art market

AUDIO: Sea Lion Predation in the Pacific Northwest

Native America Calling: Tribal colleges see an uncertain federal funding road ahead

Native America Calling: Short films taking on big stories

Native America Calling: Advocates push back against new obstacles to Missing and Murdered Indigenous Relatives momentum

Native America Calling: For all its promise, AI is a potential threat to culture

NAFOA: 5 Things You Need to Know this Week (November 24, 2025)

Chuck Hoskin: Cherokee Nation invests in rural transportation

Native America Calling: Native candidates make strides in local elections

More Headlines