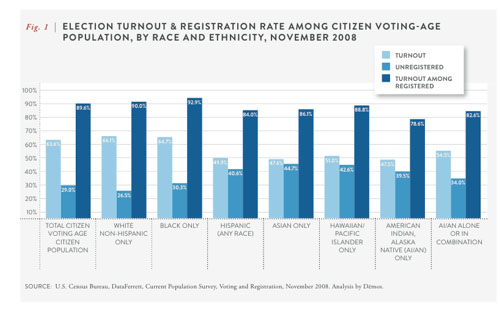

American Indians and Alaska Natives have the lowest voter participation rate by race and ethnicity, according to a new study by Tova Wang, a senior democracy fellow at Demos. The report was released this week by the National Congress of American Indians with proposals to boost participation by Native American citizens.

Voting should be easy, almost routine. If it’s election day ... we should vote. It’s that simple because it’s the very foundation of democracy. It is only when “we” have a say in what happens next, in our future, that governance meets the basic test of a democracy. But, too often, that’s not the case for American Indians and Alaska Natives. This week the National Congress of American Indians called the problem of access to voting a “civic emergency” requiring an immediate fix. “Native people have remained one of the most disenfranchised group of voters in the United States. Today as a result, only two out of every five eligible American Indian and Alaska Native voters are not registered to vote, in 2008 over 1 million eligible Native voters were unregistered,” said Jefferson Keel, president of NCAI, the nation’s oldest and most representative tribal advocacy organization. Keel said that starting this week, “we all must be unified we all must be unified by one mission – we must mobilize like never before – register tens of thousands of people, and turn out the largest native vote in history.” One way that can happen is to increase the velocity of voter registration by going to places where Native Americans already gather. One such magnet is the local clinic. A new report from Demos explains why the Indian health clinic is ideal: “Appropriate IHS facilities should be designated as official voter registration agencies along the same lines as state based public assistance agencies are now designated under the National Voter Registration Act.” This basic idea has worked in other places where low-income voters register at public assistance agencies. Demos found that when the law was implemented tens of thousands of new voters were added in North Carolina, Virginia, Missouri, Ohio and Illinois. “In Illinois, the number of public agency registration applications is now at levels 18 times the rate before re-implementation” of that voting registration law. That’s exactly the kind of boost that would be needed to register a million American Indian and Alaska Native voters. This process would also be cost-effective voter registration, the Congressional Budget Office estimates the total cost at less than $500,000 over a four-year period. “The Native community in the United States is increasingly making its voice heard in state and national elections,” the Demos report said. “Unfortunately, most of our history has been one of state mistreatment and exclusion of indigenous peoples. There are still problems and tensions ... Making voter registration easier and more accessible through designation of Indian Health Service facilities as voter registration agencies will not solve all the problems that are causing low rates of participation among American Indians and Alaska Natives or fully address the ongoing mistrust. Nonetheless, it would be an important step that would have a significant positive impact on the voting rights of thousands of Americans.” The good thing about this plan is that it builds on the successful voter efforts that are already out there, such as Native Vote. The impact of native voting has already impacted elections in Alaska, Montana and beyond. But that success has been limited by a smaller voter pool than what could be. Imagine if the numbers were increased by one million. This next election at the local, state and federal level, is all about austerity and the nature of government. NCAI has already called for the biggest turn out of Indian Country voters in history -- and that’s exactly right because there’s no better time for American Indians and Alaska Native voters to have say. Especially when that means tens of thousands of new voters. Then, given the chance, those voters will make elections routine. Mark Trahant is a writer, speaker and Twitter poet. He is a member of the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes and lives in Fort Hall, Idaho. Trahant’s new book, “The Last Great Battle of the Indian Wars,” is the story of Sen. Henry Jackson and Forrest Gerard.

Join the Conversation