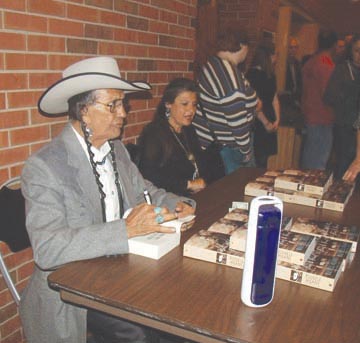

Russell Means greets participants of the Dakota Conference at Augustana College in Sioux Falls on April 27.

SIOUX FALLS, SOUTH DAKOTA –– A conference to discuss Wounded Knee, now and then, caused a bundle of mixed emotions. Augustana College’s Center for Western Studies hosted their annual Dakota Conference April 27-28. The conference examined issues of contemporary significance in their historical and cultural contexts. Approximately 80 presenters from as many as 15 states gathered to present papers and participate in panels at this two-day national conference. The conference sought the participation of Native Americans in sessions and panels. Past Native speakers have included Virginia Driving Hawk Sneve, Tim Giago, Charmaine White Face, Lydia Whirlwind Soldier and Elizabeth Cook Lynn. This year, the theme was based on both the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre and the 1973 Wounded Knee Occupation, which lasted 71 days. One of the most notable speakers was Russell Means, who, during the 1973 occupation, assumed a leadership position within the American Indian Movement. Means addressed a large crowd in an on-campus chapel, eliciting many laughs as he recounted some of the lighter moments of his entry into the AIM leadership. “I asked Dennis (Banks), ‘How do you join AIM?’” recalled Means. “He answered, ‘You just did!’” Despite this entertaining and educational interaction with conference participants, which included a large number of Augustana students, another of Means’ appearances was rife with tension. An incident more representative of the mixed bag of emotions the conference stirred up occurred during a discussion Means participated in that led to questions posed by Stew Magnuson, author of “The Death of Raymond Yellow Thunder: And Other True Stories from the Nebraska-Pine Ridge Border Towns,” which highlights the racial tension found around the reservations in South Dakota. Magnuson, who participated in the conference as a keynote speaker during the first night’s dinner presentation, questioned Means about Ray Robinson, a black civil rights activist who traveled to Wounded Knee in 1973. Robinson has never been heard from or located since. Means responded by standing and addressing Magnuson: “I’m going to tell you this – no charges from 1974 to 2002. Did anyone hear of Ray Robinson? Did anyone ever shoot him, stab him, beat him or disappear him?” “It was a generation later that the badmouthing of Wounded Knee continues,” Means said. “You and people like you are to perpetuate this erroneous image you have of who we are. And I’m sick and tired of you bringing up these false accusations based on what? Nothing!’” Means further expressed his anger that AIM has been repeatedly associated with Robinson’s disappearance. Robinson’s wife, Cheryl Buswell-Robinson, was in attendance at the conference. She has concluded that her husband is more than likely deceased and only seeks to provide a proper burial for him. During a panel discussion that included David Gienapp, James McMahon and David Price, who was an FBI agent assigned to the Pine Ridge Reservation immediately following the occupation, drew criticism from several audience members, including one Native man who questioned Price on the Anna Mae Aquash murder case. The audience member asked if there was any justification in the release on a personal recognizance bond of Aquash after her initial federal weapons charge and her subsequent release after an arrest in Oregon. The audience member also asked if Price realized that her arrest and immediate release from custody would have possibly led AIM leadership to suspect Aquash as an informant for the FBI. Price responded by saying that he felt he had been used by AIM as a scapegoat to grab headlines, and that they, AIM, were the ones killing their own. When asked by Native Sun News if he personally felt any remorse for the fact that entire communities were torn into two factions -- AIM and Guardians of the Oglala Nation (GOON), which many tribal members felt was in collaboration with the FBI -- Price stood firm in his belief that the FBI did nothing wrong during the period, saying, “You can’t fight with me over something that I didn’t do or that I wouldn’t ever want to hurt anyone with. Part of the problem is that I don’t know what the problem is. You live there. I don’t. Now I’m babbling. I’ve been gone since 1977.” When asked by NSN about how, nearly 40 years later, the Pine Ridge Reservation is still reeling from the trauma of the occupation by events instigated on both sides of the standoff and how subsequent generations are still dealing with the aftermath of the many tragedies that ensued, Price said he wants the best for the people of the reservation, but will never return. “I don’t want to go near it,” said Price. “It would be a disaster for me, but I wish you well.” (Contact Karin Eagle at staffwriter2@nsweekly.com)

Join the Conversation