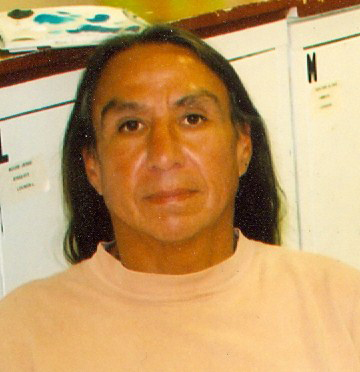

From top to bottom: Russell Hubbeling, Garfield Feather, Jesse Rouse and Desmond Rouse

MARTY, SOUTH DAKOTA –– In 1994, brothers Jesse Rouse and Desmond Rouse and their cousins Garfield Feather and Russell Hubbeling were convicted in federal court of abusing five nieces, who were aged 20 months to 7 years at the time. Recently, the National Center for Reason and Justice (NCRJ) agreed to take on the cases of the four Yankton Sioux men. The four men were each sentenced to as many as 33 years in prison on the basis of coerced testimony of young children, according to NCRJ Executive Director Robert Chatelle. Roderica Rouse, mother of one of the alleged victims and sister of Jesse Rouse, said, “After all these years, it’s just great. I know my brothers and cousins are innocent, and my mother went to her grave believing that.” Chatelle has described the trial as tainted by racism. After reports of jurors mocking Native Americans, the trial judge held a hearing on the issue. One juror admitted to laughing at another’s comments about Native people and relating to coworkers that she’d heard Native American men had sex with young girls as part of their culture. These types of statements have previously been enough to reverse a conviction. When the defendants appealed their convictions on that and other grounds, one of three federal judges hearing the matter called the evidence of bias “a matter of grave concern.” The court granted the four a retrial, with two judges voting for a new trial and one against. “Here four Native Americans placed their liberties in the hands of all whites: prosecutors, defense counsel, judge and jury,” wrote Judge Myron H. Bright in his 1996 majority opinion. “The law requires that they receive a fair trial without the impact of racial bias.” In the 1996 minority opinion, Judge James B. Loken called the trial careful, fair and impartial and took exception to Bright’s criticism of government officials, particularly the trial judge, Lawrence L. Piersol. “That I cannot abide,” Loken wrote. Subsequently, the U.S. Attorney’s Office appealed the decision to grant a retrial, and the court reversed itself in 1997. In January of 1994, squad cars arrived at the home of Jesse and Desmond’s mother, Rosemary Rouse, on the Yankton Sioux Reservation. More than a dozen children were removed from the home, apparently without any investigation or evidence received by authorities. According to witnesses, some of the children tried to run away. As they were chased down, officers threatened adult relatives with arrest if they interfered. No officials clarified the reason for their actions, according to Feather. He and the other men were arrested and charged in the succeeding days and weeks. According to Bright, in the following months, the youngsters’ parents were told “their children would be taken away again if they talked to or cooperated with defense counsel.” After the trial, the parents were warned again. “The defense attorneys told us that if we ever talked to our kids about what had happened, someone would take them so far away we’d never see them again,” said Roderica Rouse. “We were terrified.” In taking the cases, NCRJ relied on the work of prominent investigator Martin Yant, who called the trial “a judicial atrocity” and said aggressive questioning by frightening authority figures contaminated the Rouse youngsters’ memories before they got to the trial and made it impossible to ascertain the accuracy of their testimony. According to court documents and recently recorded videotapes, the alleged victims claimed at the time that at various points, food, water and bathroom breaks were withheld by investigating authorities; they were given medication that put them to sleep and caused them to vomit; and they were held in frightening, isolated situations. No audio or video recordings of the initial interview sessions were made, which was unusual, said defense consultant and trial observer Hollida Wakefield, a forensic psychologist who specializes in interviews of children. “The scientific literature has established that interviews of children must be taped to determine whether leading questions were asked,” she said. The U.S. Attorney’s Office and Department of Social Services did not allow the defense to interview the child witnesses before the trial in order to prepare questions for them, according to the 1996 appeal. “When a child witness is in the legal custody of a social services agency, that agency as custodian may refuse requests for pretrial interviews,” opined Judge Loken in the 1997 decision not to have a retrial after all. Allowing such sessions could traumatize the children and “raise a barrier” for the prosecution, the judge wrote. Nine children who adamantly refused to say their uncles had abused them were sent home. According to Chatelle, the cases of Feather, Hubbeling and the Rouse brothers display patterns NCRJ has seen before, including the burden of proof shifting – improperly – to the defendants. Lucretia Rouse of Marty, one of the alleged victims, recently released a written public statement, a copy of which was emailed to and examined by Native Sun News. Rouse, now 24, was 6 years old at the time of the raid that led to the arrests of her accused uncles. Rouse recalls being sent to a white foster family who put all the children to work on their farm. She remembers being separated by DSS and put before lawyers to be perjured to. “These lawyers and the foster parents all said that we all could go home and be home with our moms; that this will be okay to lie and we could go home” Rouse said in her statement. “So we all lied to see our family again, and that was a lie.” “After all that, we never got to see or hear from our family, like the lawyer said we would, and we kept moving around from foster home to foster home. I dropped out of school because of the pain my family went through; because of our last name and our history that was never told by anyone,” Rouse recalled. “No understanding, just judging us by not knowing our family history or what us children went through.” Rouse stated that she and the other children have suffered a lot of stress and pain from being lied to by lawyers who convinced them to make these allegations against their relatives. “All I want is my uncles back home with us once again. A happy family like any other family in America,” she said. “I, Lucretia Rouse, ask for your help and for the right justice for my family and my uncles. Please help me seek justice for my innocent uncles … This is my story.” An April 2 meeting is scheduled with the chairman and general tribal council of the Yankton Sioux Tribe for the Rouse children and relatives of the two other men. The alleged victims and their families will ask the tribe to investigate the corruption and professional misconduct of tribal social services, which allowed this tragedy to happen. The meeting will be in Wagner at the tribal building. (Contact Karin Eagle at staffwriter2@nsweekly.com)

Join the Conversation