Massachusetts' only federally recognized tribe waived its sovereign immunity by agreeing to state jurisdiction on the reservation, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled on Thursday.

In a 5-1 decision, the state's highest court dealt a blow to the Aquinnah Wampanoag Tribe, based on the island of Martha's Vineyard. The justices said the tribe "clearly" gave up its immunity when it agreed to settle its land claim with the state more than 20 years ago.

The deal, approved by Congress in 1983, led to federal recognition for the tribe and the creation of a reservation. But in exchange for those rights, the court said the tribe must abide by all local and state laws and regulations.

"Here, the facts clearly establish a waiver of sovereign immunity stated, in no uncertain terms, in a duly executed agreement, and the facts show that the tribe bargained for, and knowingly agreed to, that waiver," Justice John M. Greaney wrote for the majority. "There is absolutely nothing to suggest that the Tribe was 'hoodwinked' or that its negotiators were 'unsophisticated' or did not know what they were doing."

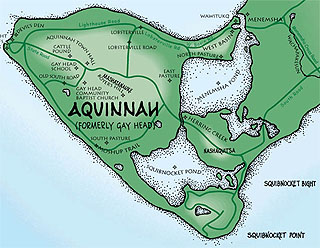

The decision means the tribe is subject to a local land-use regulation in the town of Aquinnah. Town officials sued when the tribe built a pier and a shed without obtaining a building permit. The structures were located on a pond within town limits.

But it has wider implications for other New England tribes who won federal recognition only after settling their land claims. Six other tribes in Maine, Rhode Island and Connecticut agreed to state jurisdiction on the reservation during the 1980s and 1990s. Congress approved all the agreements.

States are using the deals to exert control over tribal lands and the activities of tribal governments. In Maine, officials pressured tribal leaders to turn over internal documents after they were held in

contempt for disobeying a state freedom of information law. Over in Connecticut, officials repealed a state gambling law in hopes blocking future tribal casinos.

In a more egregious case, the state of Rhode Island raided a smokeshop on

the Narragansett Reservation, arrested several tribal members,

including women and children, and seized tribal property.

Tribes throughout the country and some members of Congress expressed

outrage at the July 2003 incident, which was broadcast on television

nationwide.

The disputes are leading to the development of case law that is not

seen as favorable to tribal interests. In Maine, the state's

highest court ruled that tribal activities affecting non-Indians or

off-reservation interests are subject to state laws.

Over in Rhode Island, a federal judge reached a similar conclusion

and said the Narragansett Tribe's smokeshop

violated state law because it "affects non-members" and isn't

"inherently governmental or political in nature."

Unlike the Wampanoag case, though, the

court did not rule that the tribe waived its immunity.

The Penobscot Nation and the Passamaquoddy Tribe took their case

to the 1st Circuit Court of Appeals but the court would not

reverse the state court ruling. The U.S. Supreme Court later refused to

review the case.

The Narragansett Tribe also appealed to the 1st Circuit, which

includes Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Maine. Oral arguments

were held in September and a decision is pending. If the Wampanoags

appeal, they would go to the same court.

The situation in the 2nd Circuit, which includes Connecticut,

has been more positive for tribes. The Mashantucket Pequot

Tribal Nation and the Mohegan Tribe were able to open casinos

after victories in the courts and two tribes whose federal recognition

is pending might be able to do the same.

The 2nd Circuit also ruled

that the federal government can take land into trust for the

tribes even after the tribes settled their land claims.

New England tribes aren't the only ones in the nation who agreed to state

jurisdiction. In Texas, the Tigua Tribe and the Alabama-Coushatta

Tribe gained federal recognition only after promising not to open casinos.

The 5th Circuit Court of Appeals later ruled that the tribes can be

sued for violating state gambling laws.

In the Wampanoag case, one justice dissented with the majority's

reasoning because he said the tribe did not

"clearly, explicitly, and unequivocally" waive its immunity.

He noted that, at the time of the agreement in 1983, the tribe was not

federally recognized.

"Therefore, it had no sovereign immunity to waive," wrote Justice

Roderick L. Ireland.

In order to gain recognition, the tribe had to go to

the Bureau of Indian Affairs, which initially rejected

the case. The tribe was finally recognized in 1987.

Get the Decision:

Aquinnah v. Gay Head Wampanoag Tribe (December 9, 2004)

Lower Court Decision:

Town

of Aquinnah v. Gay Head Wampanoag Tribe (June 11, 2003)

Related Decision:

Narragansett

Tribe v. Rhode Island (December 29, 2003)

Relevant Links:

Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head -

http://www.wampanoagtribe.net