Indianz.Com > News > Underscore.news: Choctaw Nation resists treaty promise to Freedmen

Race and Tribal Sovereignty Clash in Congressional Dispute Over Enrollment

Members of Congress are threatening to hold up housing funds for tribes. To the chief of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, it’s infringing on tribal sovereignty. For those seeking citizenship, it’s a chance to change a ‘system of hidden anti-Black racism.’

Tuesday, March 9, 2021

The chief of one of the largest Native American tribes in the United States is fighting a behind-the-scenes battle with Congress that pits racial justice against tribal sovereignty.

Gary Batton, chief of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, says he’s trying to head off efforts by powerful legislators who want to cut housing funds for his tribe unless the Choctaw change their citizenship rules. The fight spilled into public view last year, when Batton circulated a letter he wrote to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi insisting that Congress stay out of deciding who qualifies as Choctaw. Batton warned that language some members are trying to include in a routine housing reauthorization bill would amount to “holding hostage housing assistance otherwise due the Choctaw Nation.”

Batton’s letter was a rare public acknowledgement that some members of Congress are using the housing bill to force the Choctaw and other Native nations to recognize as citizens the descendants of people enslaved by tribal members.

Those descendants, known as Freedmen, were promised tribal citizenship by treaty after the U.S. Civil War. They’re still seeking it today.

The Choctaw Nation’s “continued disenfranchisement of Freedmen descendants is a carefully disguised system of hidden anti-Black racism,” wrote Angela Walton-Raji, a Freedmen researcher and genealogist, in her own letter to Pelosi. Walton-Raji, like many Freedmen, is the descendant of Choctaw citizens and enslaved Africans, and considers herself Choctaw. But Walton-Raji says she’s being denied citizenship because she’s Black.

Loading...

‘Just pure out-and-out racism’ in Native Communities

The Choctaw Nation is one of the so-called Five Civilized Tribes, nations once spread across the southeastern U.S. whose people adopted many customs of white colonists before they were forcibly relocated to what’s now Oklahoma. The citizens of the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muskogee (Creek), and Seminole Nations made a series of long marches from their homes in the 19th Century that left thousands dead and became known as the Trail of Tears. Today the Trail of Tears is a symbol of the U.S. government’s history of genocidal policies toward Native Americans. What’s less well known is that many tribal members forced enslaved people to walk the arduous Trail with them.

Batton’s letter has once again brought into the public eye the history of slavery by the Five Tribes. It also inadvertently shined a light on efforts by the descendants of those who were enslaved to become tribal members. Freedmen descendants have had some success achieving recognition from other former slave-owning tribes, notably the Cherokee Nation. But the Choctaw have consistently resisted recognizing Freedmen as citizens, even in a time when society is pushing back against systemic racism.

“Maybe they think that if they keep the Freedmen out long enough, younger generations will just forget and say ‘oh well, we’re just gonna go be Black people here,’” said Marilyn Vann, president of the Descendents of Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes Association, an organization representing the estimated hundreds of thousands of Freedmen descendants living today. Vann, a Cherokee Freedmen descendant who also has Choctaw Freedmen ancestry, successfully fought for Cherokee citizenship. She’s now running for the Tribal Council of the Cherokee Nation. She says tribal identity is as important to Freedmen as Black identity.

While Choctaw citizens don’t receive direct payments from the tribal government, a large share of the Nation’s revenues goes toward member services including healthcare, scholarships, and home ownership assistance for enrolled citizens. Formal enrollment can help with finding jobs and government contracts and allows tribal citizens to market their goods as Native art. Part of the reason the Choctaw Nation won’t enroll Freedmen, Vann says, is “not wanting to share in any of the wealth coming from the casinos, or compete with the Freedmen regarding any kind of contracts.”

A Fight in Congress

Denny Heck, who wrote the Native American Housing Assistance and Self-Determination Reauthorization Act of 2019, said the law hasn’t been updated in more than a decade and badly needs revamping to meet the housing crisis in Native communities.

“The data on both crowding and homelessness and substandard housing in Indian Country is more stark than any other demographic group in America,” said Heck, who served in Congress from 2013 until becoming Washington’s lieutenant governor this year.

But Heck said Waters wouldn’t move the bill forward unless it acted as a vehicle to “compel citizenship or enrollment” of the Freedmen, an issue Heck wanted to keep out of the housing bill. In the end, they couldn’t reach a compromise, and the bill never came to the floor for a vote.

Waters didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Now, when Congress allocates NAHASDA monies every year, they’re distributed according to outdated funding formulas. In his letter, Batton writes that he “is not aware of any other instance in recent decades where Congress has held federal appropriations hostage in an effort to force a sovereign Indian Tribal Government to violate or alter its own Constitution.” But there is some precedent for Waters’ efforts. Congress in 2007 froze the Cherokee Nation’s federal housing funds when then-Chief Chad Smith disenrolled the Cherokee Freedmen.

Batton didn’t respond to a request for comment, but his spokesperson said that if the reauthorization bill is passed with Waters’ language included, it “would force the Choctaw Nation to amend their constitution without the vote of the people and would withhold funding from our tribal members most in need.”

Enslaved on the Trail of Tears

Prior to the invasion of European colonists, the Choctaw, like other tribes, practiced less permanent forms of slavery, usually involving prisoners of war who were eventually released or naturalized into the tribe.

After Europeans arrived, the Choctaw adopted colonists’ form of Black chattel slavery. White settlers married into the Choctaw tribe. Some mixed families established plantation dynasties built on enslaving Black people.

Chief Peter Pitchlynn, who was instrumental in establishing the Choctaw Nation in Indian Territory after the Trail of Tears, enslaved around 80 people himself. People Pitchlynn enslaved picked 62,500 pounds of cotton on his plantations between 1861 and 1865 for distribution amongst the Choctaw people. Walton-Raji’s great uncle Albert Burris was the child of two people enslaved by Chief Pitchlynn.

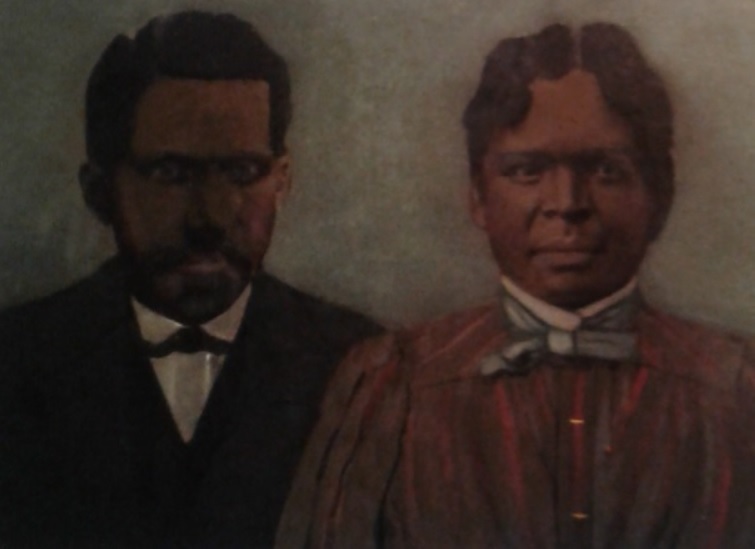

Some Choctaw families even sold furniture and other possessions to buy enslaved people they forced to join them on the Trail of Tears, says Walton-Raji. “Slavery wasn’t pushed upon them at all. They voluntarily took slaves, and continued to purchase them,” she says. Walton-Raji has memories of her own great-grandmother Sallie Walton, who was born into slavery and lived to be 98 years old.

“My great-grandmother would let me sip out of her cup of sassafras tea,” Walton-Raji recalls. “She would pour some of it in a saucer and blow on it, and let me sip it from the saucer.” Sassafras, or kvfi, is a part of Choctaw culture important enough that it has a month named after it.

Delay, Enrollment, and Disenrollment Again

After delaying for almost two decades, the Choctaw Nation finally enrolled the Freedmen as tribal citizens in 1883. But the enrollment would prove temporary.

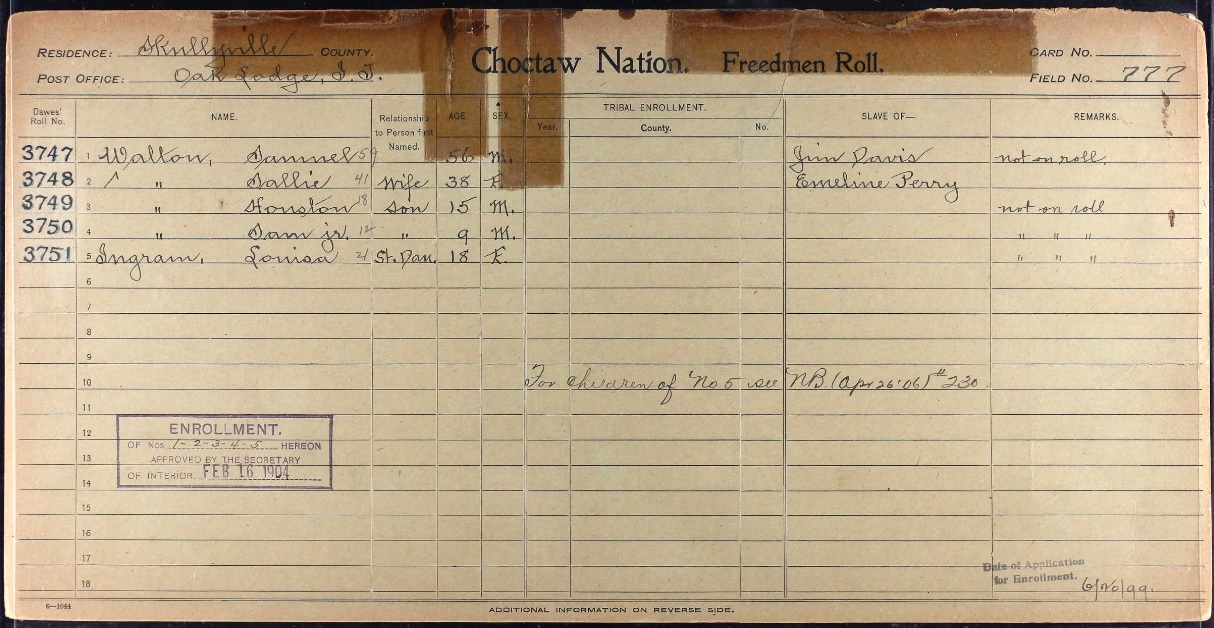

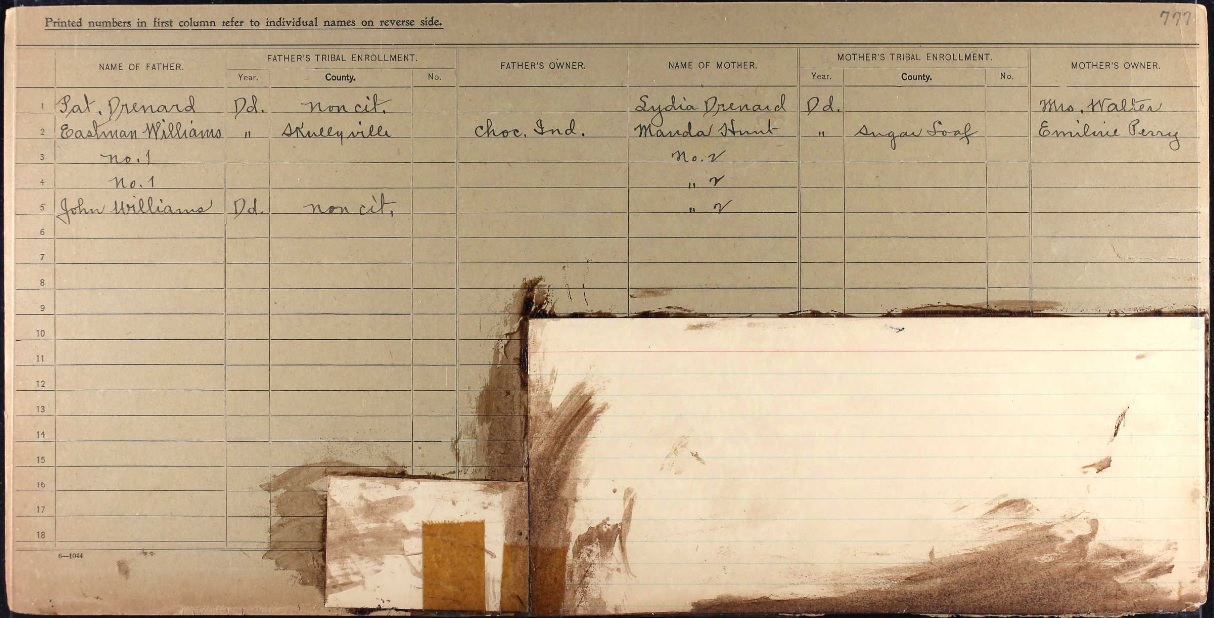

In 1893, the U.S. created the Dawes Commission to limit the Five Civilized Tribes’ enrollment and land holdings, part of a strategy to dissolve Native identity. Census takers declared virtually anyone they could identify of African descent as Freedmen – even if the Freedmen also had Native ancestry. Nearly a century later, the Choctaw Nation approved a constitution that relies on similar calculus to determine citizenship. Under the 1983 Choctaw Constitution, descendants of people identified as Freedmen by the Dawes Commission cannot enroll in the tribe.

Walton-Raji has the census card for her great-grandmother. And despite the fact that it identifies Sallie Walton as the daughter of a Choctaw citizen, Sallie herself is identified as “Freedmen.” Therefore, Walton-Raji is ineligible for citizenship.

“So our blood doesn’t count,” Walton-Raji says. “Our blood does not matter.”

Breaking the Treaty of 1866 could be the Cherokee Nation's undoing. #Cherokee #CherokeeFreedmen #HonorTheTreaties @ChuckHoskin_Jr @CherokeeNation @Anadisgoi https://t.co/FZuXMWHnLF

— indianz.com (@indianz) February 26, 2021

Sovereignty or ‘States’ Rights’?

Vann compared Batton’s appeal to tribal sovereignty to the states’ rights rallying cry used during the South’s opposition to integration. “All those old racist rednecks back in the day, they all sat hollering about states’ rights,” Vann said. “What is the difference?”

Walton-Raji echoes that comparison. “Growing up in Arkansas, I know what ‘states’ rights’ means,” she said. “It’s a code word that former Confederate sympathizers use to say ‘we have a right to treat people of African descent, or people with African blood, any way we wish.’”

The federal government’s relationships with tribes, however, is different than its relationships with states.

“The U.S. would be violating tribal sovereignty if they financially pressured the Choctaw Nation into enrolling Freedmen,” says Kyle T. Mays, Saginaw Anishinaabe, who is assistant professor at UCLA’s Department of African American Studies and the American Indian Studies Center. “I don’t think the U.S. government has any business involving themselves.”

At the same time, Mays acknowledges the Choctaw Freedmen have very little recourse. “I think they have a right to petition someone for their rights, and the only option for them is the U.S. government,” he said.

Brian Oaster (they/them) is a member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, and a freelance reporter working in the Pacific Northwest. Their stories have appeared in papers like Street Roots, Portland’s award winning non-profit weekly that focuses on social justice, and Indian Country Today, the nation’s most widely read Native newspaper. Brian also occasionally does radio work for KBOO Community Radio Portland. They have a particular interest in Native issues where they intersect with environmental and racial justice, urban development, housing issues, and representation in the arts. Follow them on Twitter @brianoaster.

This story originally appeared on Underscore.news, a nonprofit journalism organization based in Portland, Oregon. Supported by foundations, corporate sponsors, and the public, our reporting focuses on underrepresented voices and in-depth investigations.

Search

Filed Under

Tags

More Headlines

Montana Free Press: Blackfeet Nation citizens cite treaty rights in lawsuit over tariffs

Cronkite News: A ‘mural with a message’ rises in Arizona

Chuck Hoskin: Cherokee Nation is an economic powerhouse

Native America Calling: Philanthropy fills in the gaps

AUDIO: Examining 50 years of the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act in Indian Country

Native America Calling: The next 50 years of self-governance

Cronkite News: Food sovereignty movement promotes Native foods

VIDEO: Examining 50 years of the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act in Indian Country

Native America Calling: Fresh Native creativity with a new play and new television show

AUDIO: Native American Education – Examining Federal Programs at the U.S. Department of Education

VIDEO: Native American Education – Examining Federal Programs at the U.S. Department of Education

Native America Calling: Indigenous business and the unpredictable new trade landscape

Written testimony for Senate Committee on Indian Affairs hearing on Department of Education

Native America Calling: An imbalance of deadly force by police in Canada

‘Betrayal’: Indian Country slams closure of Department of Education

More Headlines

Cronkite News: A ‘mural with a message’ rises in Arizona

Chuck Hoskin: Cherokee Nation is an economic powerhouse

Native America Calling: Philanthropy fills in the gaps

AUDIO: Examining 50 years of the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act in Indian Country

Native America Calling: The next 50 years of self-governance

Cronkite News: Food sovereignty movement promotes Native foods

VIDEO: Examining 50 years of the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act in Indian Country

Native America Calling: Fresh Native creativity with a new play and new television show

AUDIO: Native American Education – Examining Federal Programs at the U.S. Department of Education

VIDEO: Native American Education – Examining Federal Programs at the U.S. Department of Education

Native America Calling: Indigenous business and the unpredictable new trade landscape

Written testimony for Senate Committee on Indian Affairs hearing on Department of Education

Native America Calling: An imbalance of deadly force by police in Canada

‘Betrayal’: Indian Country slams closure of Department of Education

More Headlines