Indianz.Com >

News > Underscore.news: National Park Service gains Native director for first time in history

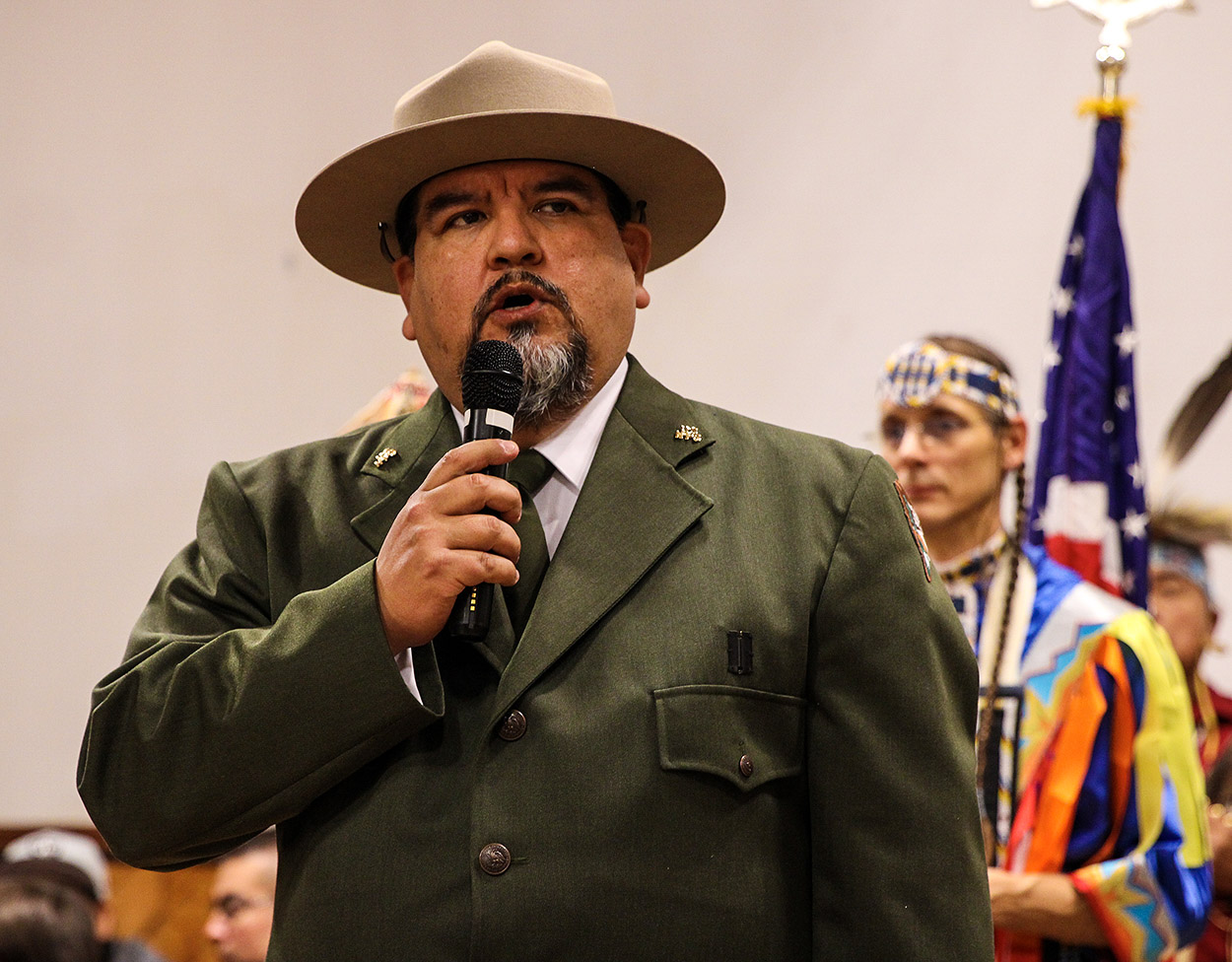

Chuck Sams, in his National Park Service uniform, speaks to members of the CTUIR and other visitors at the tribal longhouse on the Umatilla Indian Reservation during the tribes’ annual Christmas Celebration on December 24, 2021. Photo by Dallas Dick/Underscore.news

Chuck Sams, in his National Park Service uniform, speaks to members of the CTUIR and other visitors at the tribal longhouse on the Umatilla Indian Reservation during the tribes’ annual Christmas Celebration on December 24, 2021. Photo by Dallas Dick/Underscore.news

The Indigenous Voice at the Helm of the National Park Service

In a sit-down conversation with Underscore.news, Chuck Sams, the country’s first Native American parks director, discusses the role his agency can play in better representing Indigenous people and their stories.

Wednesday, January 12, 2022

By Wil Phinney

As the first Native American director of the National Park Service, Charles F. “Chuck” Sams III brings an Indigenous perspective to a U.S. Department of Interior agency responsible for more than 400 national parks, monuments and memorials, as well as more than 300,000 staff and volunteers.

The U.S. Senate unanimously approved Sams to serve as director on November 18. He was then sworn in December 16 by Interior Secretary Deb Haaland on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., giving the department its first Senate-confirmed director in nearly five years.

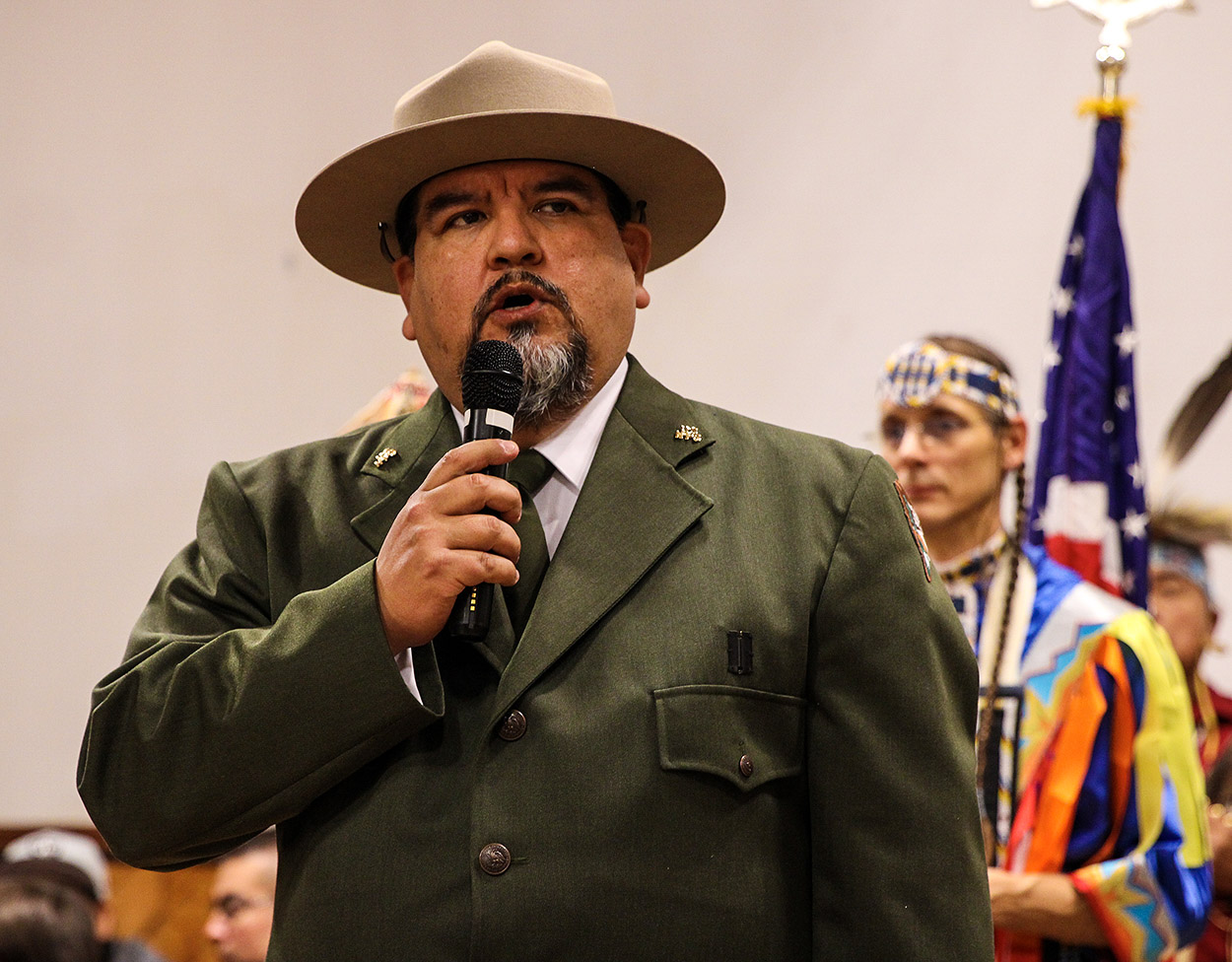

Sams, who is enrolled with the Cayuse and Walla Walla tribes and has direct blood ties to the Cocopah and Yankton peoples, is a member of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation (CTUIR), a confederation of the Cayuse, Umatilla and Walla Walla tribes. He has held several leadership roles with the CTUIR and for many years lived on the reservation, which is located at the foot of the Blue Mountains in eastern Oregon. He and his wife, Lori, and daughter, Ruby, have relocated to the D.C. area. The family was honored at the tribes’ annual Christmas Celebration on December 24 in the CTUIR Longhouse.

Indianz.Com

In a December 23 one-on-one interview with Underscore.news in Pendleton, Sams said the story of Native Americans needs to be better told at America’s 423 national parks, monuments and memorials, including the White House.

“We’re all still living cultures,” Sams said. “None of us are a dead culture yet, and I don’t plan on being part of a dead culture. And I don’t think America wants that either. I think that there’s an opportunity for us to talk about history, where we are today, and also a little bit about what we think the future will hold for all Americans.”

The history of Native Americans living on this continent since time immemorial must be told so that visitors to national parks have a more complete perspective on what it means to be American, Sams said.

“We’re not going to hide from the negative parts of our history,” Sams said. “Those are important to teach because I think by doing so we set a foundation of trying to ensure we don’t repeat that past.”

In his capacity overseeing the NPS, Sams will help implement the Great American Outdoors Act and the bipartisan infrastructure law. In addition to funding for climate resiliency initiatives and legacy pollution cleanup, the infrastructure law provides for reauthorization of the Federal Lands Transportation Program, which will invest in repairing and upgrading NPS roads, bridges, trails and transit systems.

Chuck Sams, director of the National Park Service, is honored at a grand entry in the longhouse during the annual tribal Christmas Celebration on the Umatilla Indian Reservation in eastern Oregon on December 24, 2021. Sams is flanked, from left to right, by Thomas Morning Owl, general council interpreter, and Alan Crawford and Andrew Wildbill, longhouse whipmen. Photo by Dallas Dick/Underscore.news

Chuck Sams, director of the National Park Service, is honored at a grand entry in the longhouse during the annual tribal Christmas Celebration on the Umatilla Indian Reservation in eastern Oregon on December 24, 2021. Sams is flanked, from left to right, by Thomas Morning Owl, general council interpreter, and Alan Crawford and Andrew Wildbill, longhouse whipmen. Photo by Dallas Dick/Underscore.news

Sams, who has worked in state and tribal governments as well as nonprofit natural resource and conservation management, most recently served as a member of the Northwest Power and Conservation Council, appointed by Oregon Gov. Kate Brown.

Sams has held a variety of roles for the CTUIR, including stints as interim executive director and communications department director. He has also served as president/chief executive officer of the Indian Country Conservancy, executive director of the Umatilla Tribal Community Foundation, national director of the Tribal and Native Lands Program for the Trust for Public Lands, and president/chief executive officer of the Earth Conservation Corps.

He holds a bachelor of science degree in business administration from Concordia University in Portland and a master of legal studies in Indigenous Peoples Law from the University of Oklahoma. He is also a U.S. Navy veteran.

Sams’ first recollection of visiting a national park was as a 5-year-old when his parents stopped at the Grand Canyon during a summer trip from his home in Oregon to see his mother’s family in Arizona. Since then he has visited many national parks, mostly in the western U.S. but as far south and east as Puerto Rico, and as far north as Alaska, where two-thirds of all NPS lands are located.

Indianz.Com Video: Charles “Chuck” F. Sams III Opening Statement – National Park Service

On a recent hike with his wife, Lori, and his youngest daughter, Ruby, at the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument in central Oregon, Sams said he stopped to look at a map showing every national park and monument in the U.S.

“I stopped counting at 123 of 423 that I’ve been to in one way or another,” said Sams, who has visited all 50 states through his conservation work.

“Do I have a bucket list? I don’t know, but I want to get to as many more as I can,” he said.

During his interview with Underscore.news, Sams discussed how Native Americans can be better represented at national park sites. Some of the questions and answers appear below.

Underscore (U): When you were nominated for this position, were you thinking about ways in which Native Americans and other minorities have been represented at national park sites?

Chuck Sams (CS): I’ve been thinking about that for a long time … Over the years I’d noticed that stories about Native Americans, whether it was at Pipestone (National Monument in western Minnesota), whether it was even at the Custer Battlefield (Little Bighorn Battlefield Monument in Montana), whether it was down south in the Grand Canyon or whether it was even along the East Coast, [information about Native Americans] was kind of just a passing few sentences or a paragraph.

There wasn’t really the recognition for the people who had stewarded these lands since time immemorial. Their stories have not really been told … It’s not just telling our story, the American Indian story. It’s also telling other people’s stories.”

U: Do you think the narrative of tribes is adequately presented throughout the National Park System?

CS: I think that it’s getting better. I mean, you have watched the significant changes that happened at Whitman Mission (National Historic Site near Walla Walla, Washington). The narrative that I grew up on living here in eastern Oregon was that it was a massacre, an unprovoked massacre that happened on the Whitman Mission (in 1847). And that’s how the story was told when I went over there in fourth grade. You now know that the partnership that the National Park Service has with the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Reservation has expanded that story to tell both sides. And I would even say the narrative on the non-Indian side has changed significantly in the last 20 years.

Both Cecilia Bearchum (deceased) and Marjorie Wahaneka (elders of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation) led a lot of that Whitman Mission effort in a way that was non-threatening. Their mission was education — not to threaten anybody, but to say there’s always two sides to every story. Each side of that story is valid from that person’s perspective. Both of those people have been great mentors in my life. When I was going to college they both made sure that I didn’t forget where I came from and who I was.

Kat Brigham, chair of the board of trustees for the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, presents a Pendleton blanket to Chuck Sams in the longhouse during the tribes’ annual Christmas Celebration on December 24, 2021. Photo by Dallas Dick/Underscore.news

U: Do you have a plan to improve the Indigenous perspective?

CS: Secretary of Interior (Deb) Haaland has made it very clear that we are working on better consultation. The president of the United States has issued an executive order on consultation with tribes and that consultation with the National Park Service has to be meaningful in how we’re providing interpretation within the park systems. We will be reaching out and talking with tribes; Secretary Haaland will be going out in January to begin some of that consultation. I will also be traveling out to different regions to talk with tribes and figuring out where we can do better interpretation, where we can ensure better access to tribes. How are we fulfilling that trust responsibility?

U: What part can tribes play in developing or shaping their stories?

CS: Their stories are pretty well told among their people, but their stories need to be validated and heard so that they can feel that there is a trust between them and the federal government, the National Park Service. Tribes have to be prepared to tell their stories as they want to tell them while making sure that we are partners in getting the information into the record. I would expect there wouldn’t be any issue with tribes joining the effort. I would hope not. I think a lot of tribes, at least in my very short time, really want to find a healthy way to partner with the National Park Service.

U: As I understand it, there were many American Indians living in the area of Yellowstone National Park when it was dedicated by President Grant. Obviously, they were displaced.

CS: Eventually they were displaced, but the remnants of their villages actually lasted until the 1960s. Tribes still have usual and accustomed rights in those parks and while they’re not currently hunting, they are still gathering within those parks. Matter of fact, there are a number of federal agreements between the National Park Service and tribes to ensure that they have the ability to go in and collect traditional foods and medicines, to be able to conduct prayer and ceremonies within the park system.

U: How can more Native Americans be enticed to visit national parks? The majority of people who visit national parks are white.

CS: They are and we’re trying to figure out exactly why that’s so, and what are the influences behind that so that we can help ensure that all people feel comfortable when they come into the national parks, that they know that they’re welcomed into their national parks. You know, for American Indians, they only need to show their tribal ID and they can get in for free.

I feel very lucky as a kid growing up with relations in Arizona. One of the first parks I can vividly remember going to see was the Grand Canyon as we were heading through Arizona to go to see my grandparents in Somerton and Parker, Arizona. My father ensured that we got to see Crater Lake (Oregon’s only national park). We went up into the Olympic Peninsula into Olympic National Park. As I got older, we would travel to Montana to go visit family and go into Grand Teton (National Park) and Yellowstone. I think that there are Native families, if they continue along their traditional routes and going off to see relatives and their family, (they) have an opportunity to go into the national parks and should feel welcomed into those national parks.

U: Do you think with national park monuments and parks in their vicinities that tribes can better use those locations to improve their own tourism?

CS: The John Day Fossil Beds National Monument abuts the homelands of the Cayuse, Umatilla and Walla Walla along with the Warm Springs (Indians of Oregon). Those relationships, I think, could garner better support through agreements where we can then enhance each other’s tourism. So even though John Day is two hours away from us here, it doesn’t mean that somebody who’s on a family trip couldn’t see and experience and want to know more about the Cayuse, Umatilla and Walla Walla and come here to the Umatilla Indian Reservation or swing up north and take a route through Warm Springs and then back over to here. And I think that can happen all over the United States, whether that’s in Alaska or whether that’s working with the Seminoles in the Everglades (National Park in Florida). There are great opportunities for communities and tribes to work together to promote tourism.

Chuck Sams with his wife, Lori, and daughter, Ruby, on a hike in Oregon’s John Day Fossil Beds National Monument in 2021. Courtesy of the Sams family

U: Can tribes do a better job of promoting their own tourism through information or presentations?

CS: The American Indian Alaska Native Tourism Association has just started an agreement in the West here to do just that. And they’re trying to figure out exactly how to not only get into those kiosks, but to get into the interpretation centers, to get in and be able to do those presentations. Again, it’s being able to use the synergy between national parks and tribes so that economic value comes to not just the park, but also to the gateway communities and the tribes themselves.

I think there are great opportunities for tribes to bring speakers into parks to talk about the history — from the beginning of time to contemporary history. There are opportunities to do arts and crafts within the parks and to show and demonstrate Native skills, whether that’s using quill work or bead work to how craftsmen are able to shape stones.

U: When we talked earlier you mentioned all the different sites and projects that the National Park Service operates or manages besides parks. What are those? You talked about monuments, wild and scenic rivers, and so on.

CS: We help in the implementation of the planning and work with local communities on wild and scenic rivers. We work on heritage areas where we provide planning to local communities so that they can promote their culture and their heritage in their area. Actually, there are more national monuments and memorials than there are national parks. And these are everything from a small open space to a little house commemorating a former president or a historical figure. We have over 20,000 staff members in the National Park System, working in all of these places, in every nook and cranny of the United States and U.S. territories. And then we have over 300,000 volunteers who support that staff to do interpretation, to do maintenance, to do things like invasive species removal. That’s a very large workforce of over 320,000 people who really feel it’s their job to go out and encourage and bring Americans in to see what they own and be a part of, right down to Oregon where we have Crater Lake National Park. That’s the only national park in the state of Oregon, but you also have the John Day Fossil Beds and Fort Astoria (Lewis and Clark National Historical Park) with its interpretation out there on the coast.

U: How is the Native perspective presented at John Day or Astoria or Crater Lake?

CS: The Klamath Tribes have their own creation story about Crater Lake. It is about Wizard Island when they came up and out of the earth at Crater Lake. And at Fort Astoria, there’s the discussion of when Lewis and Clark got there and the tribes, the Nehalem, the Tillamook, the Indians that they met up with in that territory. On the Columbia River it’s about the Chinook Indians and the trading that they did initially with the explorers and the recognition that that expedition might not have survived that harsh winter had they not partnered with the tribes and were able to get resupplied and shown the lay of the land. That was pretty wet and that was pretty cold. And it can be treacherous. They recognized the Columbia Bar was a very dangerous way of trying to come in and out of the estuary. They had to hunker down for months, but the tribes told them that we have long canoes. There’s only certain ways to get in and out between the ocean and into the big river. So yes, that story is told.

U: You mentioned that two-thirds of the National Park Service acreage is in Alaska.

CS: Out of the 85 million acres, over 50 million acres of it is in Alaska alone. And so it’s very large; it’s very complex. There are a lot of issues on how to manage that appropriately between Native Alaskan villages and Native Alaskan Corporations with the state of Alaska. Alaska itself is very unique in how it came into the Union and how the land was divided between federal lands, state lands and Alaska Native lands … And so you have to really look at the laws that set up both the Native Corporations and the lands within Alaska and have a better understanding that laws that apply in the lower 48 don’t apply in Alaska.

U: Is Indian law part of the management, etc., of national parks?

CS: I don’t know if it always has been, but it should have been. I think that by getting an Indigenous law degree I can see where it’s been that same old, you know, ‘Just because you’re ignorant of the law doesn’t mean that you aren’t beholden to the law.’ And I think because nobody fully understood their obligations under federal Indian law that it just either was ignored or just kind of set aside. I think that this administration is committed to upholding federal Indian law and you have a Secretary of Interior who’s very committed to that. I believe those relationships will continue to develop and improve.

This story originally appeared on Underscore.news, a nonprofit journalism organization based in Portland, Oregon. Supported by foundations, corporate sponsors, and the public, our reporting focuses on underrepresented voices and in-depth investigations.

Wil Phinney has been a reporter and editor for more than 40 years at newspapers in Oregon, Wyoming and Montana. He recently retired after 24 years as editor of the Confederated Umatilla Journal, the award-winning monthly newspaper on the Umatilla Indian Reservation in eastern Oregon. He lives in Pendleton, Oregon, with Carrie, his wife; they have three daughters.