Indianz.Com > News > Being Frank: How do we stop tire debris from killing coho salmon?

How do we stop tire debris from killing coho salmon?

Wednesday, November 24, 2021

Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission

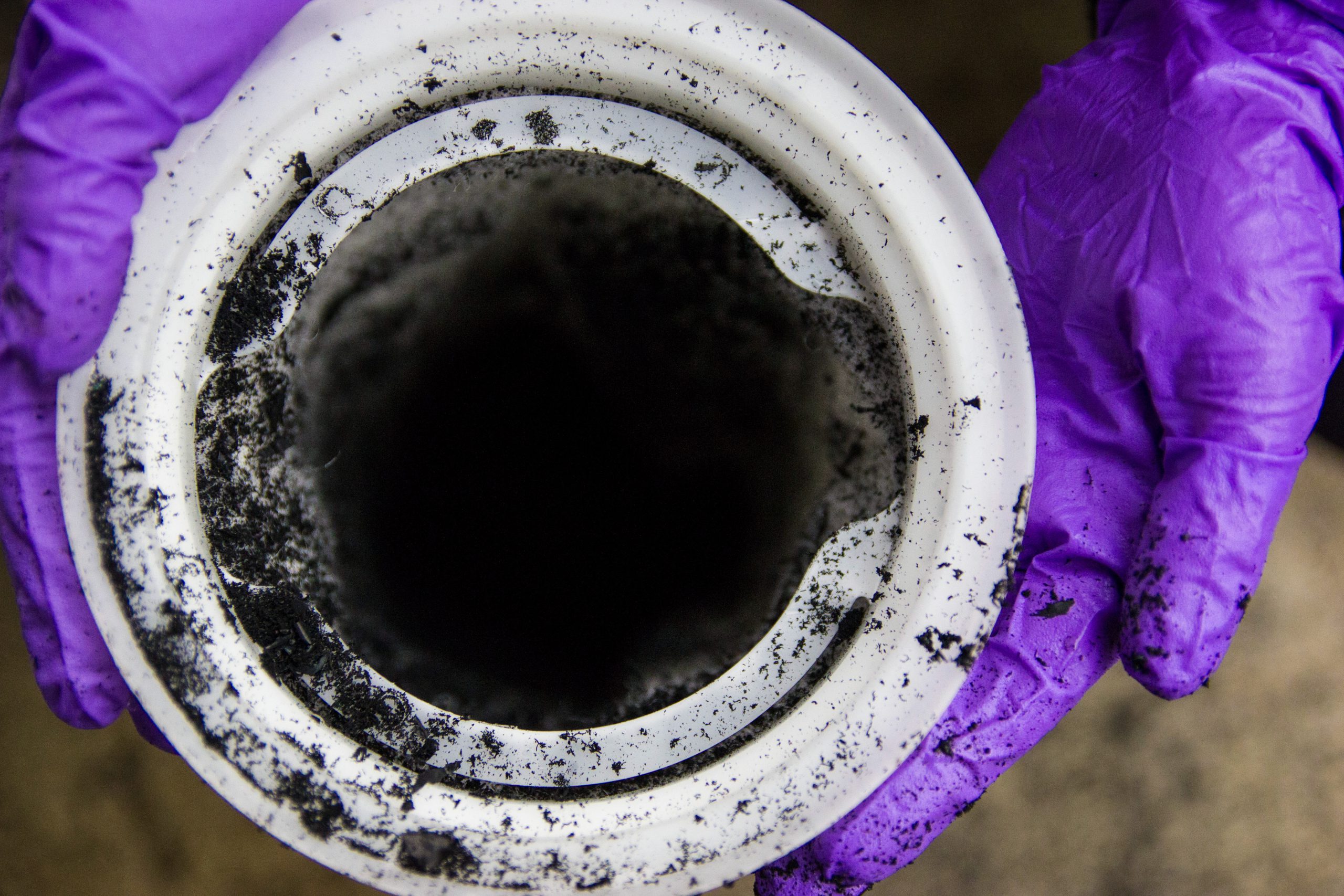

Now that we know a chemical in our car tires is killing salmon, we have to act urgently to keep it out of the water.

Research published last year confirmed that the preservative 6PPD interacts with ozone to kill coho salmon even in low concentrations in a short amount of time. The study led by Jenifer McIntyre of Washington State University was conducted over a decade in partnership with the University of Washington at the Suquamish Tribe’s Grovers Creek Hatchery.

In the salmon recovery world, it’s rare that we’re able to pinpoint the exact chemical at fault. These findings are a smoking gun for the collapse of coho salmon throughout Puget Sound, especially in the urban and developing areas where roads and salmon intersect.

Coho populations are at an all-time low, having declined steadily since the 1980s. At the same time, we’ve seen the expansion of road systems into rural areas. While there are other factors that have led to declining salmon runs, science has shown that 6PPD is a piece of the puzzle.

Being Frank is a column from the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission that represents the natural resources management interests and concerns of the treaty Indian tribes in western Washington.

Search

Filed Under

Tags

More Headlines

Ryman LeBeau: Native nations must remind America of the truth

Native America Calling: Storytelling season

Native America Calling: Tribes celebrate major landback wins

VIDEO: S.5355 – National Advisory Council on Indian Education Improvement Act

VIDEO: ‘Nothing about me, without me’

VIDEO: H.R.1101 – Lumbee Fairness Act

VIDEO: S.3857 – Jamul Indian Village Land Transfer Act

Native America Calling: A look at 2024 news from a Native perspective

AUDIO: ‘The Network Working Against the Lumbee Tribe’

VIDEO: ‘The Network Working Against the Lumbee Tribe’

Tribal homelands bill on agenda as 118th Congress comes to a close

Native America Calling: Solving school absenteeism

‘The time is now’: Lumbee Tribe sees movement on federal recognition bill

Cronkite News: Program expanded to cover traditional health care practices

NAFOA: 5 Things You Need to Know this Week

More Headlines

Native America Calling: Storytelling season

Native America Calling: Tribes celebrate major landback wins

VIDEO: S.5355 – National Advisory Council on Indian Education Improvement Act

VIDEO: ‘Nothing about me, without me’

VIDEO: H.R.1101 – Lumbee Fairness Act

VIDEO: S.3857 – Jamul Indian Village Land Transfer Act

Native America Calling: A look at 2024 news from a Native perspective

AUDIO: ‘The Network Working Against the Lumbee Tribe’

VIDEO: ‘The Network Working Against the Lumbee Tribe’

Tribal homelands bill on agenda as 118th Congress comes to a close

Native America Calling: Solving school absenteeism

‘The time is now’: Lumbee Tribe sees movement on federal recognition bill

Cronkite News: Program expanded to cover traditional health care practices

NAFOA: 5 Things You Need to Know this Week

More Headlines