Indianz.Com > News > Cronkite News: How ‘Star Wars’ is helping to preserve the Navajo language

Dubbing ‘Star Wars’: Preserving the force of Navajo language

Monday, September 20, 2021

Cronkite News

FLAGSTAFF, Arizona — Manuelito Wheeler did not join millions of sci-fi fans who packed into movie theaters in May 1977 to see the original “Star Wars.” He was only 7, and living with his family in remote Window Rock on Navajo Nation land, hundreds of miles from the nearest movie theater and with little knowledge of any galaxy far, far away.

Eighteen years later, Wheeler is the father of a 4-year-old son, sitting in the dim light of their living room one night watching the trilogy box set on VHS.

After, an idea lingered: What if “Star Wars: A New Hope,” as the original now was called, was dubbed into Diné Bazaad, the 700-year-old language of the Navajo? There were so many parallels – of duality, of colonization, of landscape in the Indigenous land and a force that drives people to connect through shared experiences.

Most of all, he thought, lacing a pop culture movie with Navajo voices could preserve the Diné language that threatened to erode in a culture that has lived for centuries. In 1980, 93% of Navajos spoke the native language. By 2010, census data showed that number had dwindled to 53%.

There were other reasons a dub made sense. “Star Wars” appeals to those young and old. Some fans can quote the movie word-for-word. Others are at least familiar enough with the dialogue to follow along in another language.

The pitch: A need for financing, Luke Skywalker runs out of gas and a fembot joins the ‘Star Wars’ universe

The thought of creating a Navajo language “Star Wars” kept tugging at Wheeler after that living room viewing with his son. Sometime in 1996, he started formulating the concept with his wife, Jennifer Wheeler, a linguist and Diné teacher.

He ordered the script through Amazon, which was just an online bookstore at the time, and asked his wife to translate the first 10 pages. He expected it back the next day. She returned in 10 minutes.

“That point is when I really thought, ‘This is possible,’” Wheeler recalled.

He started reaching out to any email he could find on the internet that was associated with Lucasfilm, the production company, and hoped for the best.

After a year, he heard back. Disney and Lucasfilm signed on – so long as Wheeler could find the money.

He first turned to the Navajo Nation for funds, but tribal elders had trouble seeing how a movie could stop language erosion.

Over 36 hours, often surrounded by boxes of pepperoni and cheese pizza and liter bottles of soda, the team worked line-by-line, with the occasional translation question. For instance, Diné has no words for “droid” or “lightsaber.”

Droid translated to beesh hxiinaanii, or “metal that’s alive.” Lightsaber, or beeshdiin, means “sword of light.”

“They would give me a friendly pat on the back, and a friendly no,” Wheeler recalled.

The premiere: A screen on a truck, and Hans Solo is moved by watching the Navajo-dubbed ‘Star Wars’

On July 3, 2013 – the world premier of the Diné dub – Junes would find out what audiences thought of the actors’ work. More than 2,000 people, many clad in cosplay, crowded onto the Navajo Nation Fairgrounds in Window Rock.

Instead of theater seating, the audience piled into a rodeo arena and watched the film on a screen stretched out on a semi-truck – although they had to wait for the dust to clear from the rodeo earlier that day.

The first triumphant note of the “Star Wars” theme blasted through the speakers, and the crowd erupted, applauding.

And then the first line of the movie, spoken by Hongeva-Camarillo, followed.

“Did you hear that? They shut down the main reactor. We’ll be destroyed for sure. This is madness.”

“Disínts’ą́ą́’ísh? Béésh naat’a’í bijéí deineestsiz. K’ad éí nihik’ihodoolchííł. Tsi’adeesdee’.”

Hongeva-Camarillo was nervous, concerned that fans would reject a woman voicing C-3PO. Instead, her performance was met with hoots and hollers, and a wave of excitement.

Yazzie sat in the crowd, too, feeling bittersweet. She watched elders and children alike listen to their age-old language reverberate through the speakers.

When Yazzie was in high school, she was in several theater productions in Diné. Her grandmother was her biggest fan. But by the time the dubbed “Star Wars” premiered, her grandmother had lost her hearing.

Junes, too, felt immense excitement and pride when Han Solo first flashed on-screen, and his voice filled the arena. And though he vividly remembers his scene, it’s an image off-screen that sticks with him.

“There was a grandchild and a grandma sitting three rows up from me, watching the same movie in one language. And they both could understand it,” he said.

Junes, his voice catching as he recalls that night eight years ago, said he grew up in a violent home and overcame drug and alcohol addiction as a young adult.

Reflecting on his personal journey, Junes spoke softly.

“That’s my proudest moment,” he said.

The language: Taking a centuries-old language far, far into the future

Many Native speakers are working to make sure the next generation preserves Diné in an effort to revitalize dying Indigenous languages. A part of this is getting young people engaged in learning the language, and starting conversations between speakers of all ages.

That’s what led Wheeler to “Star Wars.”

The movie’s appeal spans generations, and the translation started conversations on the tenacity of the Navajo language.

“It reopens a safe dialogue for people who don’t speak Navajo that want to learn Navajo. It reopens dialogue for fluent speakers,” Manny Wheeler said.

After decades of language degradation in boarding schools that Indigenous children were first forced to attend in the 1860s and newer difficulties in sustaining language education and engagement in young generations, many Native languages are either endangered or extinct.

Once the Civilization Fund Act was passed in 1819, the federal government started enacting assimilation policies to “civilize” Native peoples, one of which established boarding schools to westernize Indigenous children. That meant punishing Indigenous children if they spoke their own language instead of English.

From 1860 until 1978, tens of thousands of children from Native communities across the U.S. attended schools, where they experienced “physical, sexual, cultural and spiritual abuse and neglect,” according to the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition.

Although not every Indigenous child was sent to boarding school, the practice resulted in generations of people with little to no connection to their native tongues.

“That’s where the link was broken,” Wheeler said.

The Navajo language is traditionally passed down orally. But, as less and less of the population retained and shared the language, native speakers swiftly declined.

“We’ve learned it from our parents talking to us in Navajo, our grandparents talking to us in Navajo,” Yazzie said. “But as the generations don’t speak it, how is the language going to get passed down?”

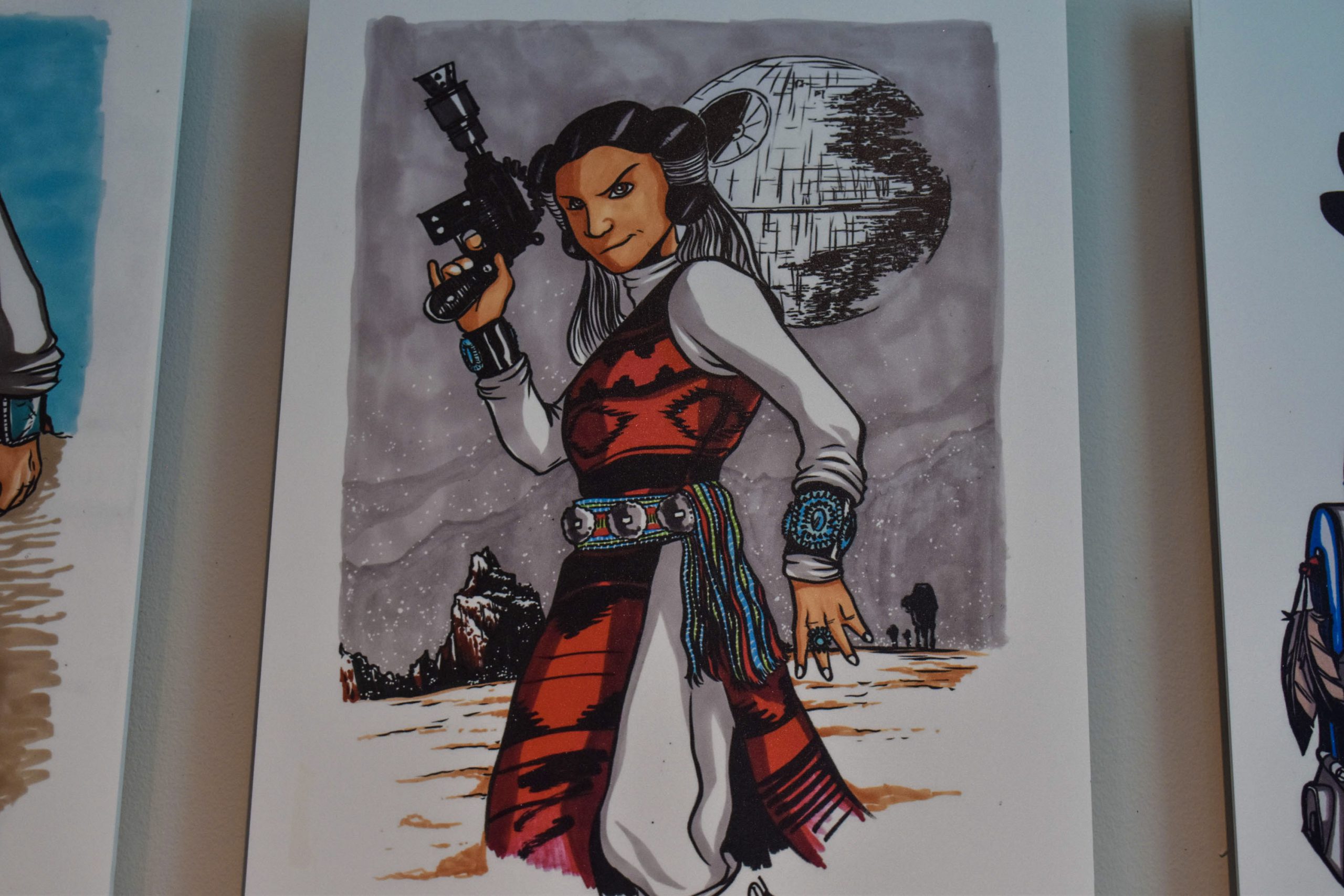

After voicing Leia, Yazzie was inspired. She started creating short language learning videos, which she posts on TikTok alongside Star War cosplay and acting videos in Diné. “I started using my role as Princess Leia as a pathway because that’s how people know me, that’s how people recognize me,” Yazzie said. “Now that I have your attention, let me teach you something.” Yazzie posts basics, such as numbers and colors, and takes translation requests from followers. It’s making a difference, she said. People young and old duet her videos and follow along with her short lessons. In one video she tackles the rainbow. Red is lichxii’ and blue is dootl’izh. She said TikTok’s short, digestible format makes it easier to retain information and attention. It fills a void for oral teaching, and supplements it with short written and spoken communication. Her ultimate goal is to engage people in the language, even if it’s just for a few moments. “It’s 60 seconds,” Yazzie said. “It’s not like you have to sit there for an hour-long lesson.”@l1ttlewolves Partial REPOST – Diné Bizaad Colors #nativetiktoks #indigenous #dinébizaad #navajo #diné

♬ Diné Bizaad Colors – ✌🏽Zee✌🏽

The art: Indigenous artists showcased in “The Force Is With Our People”

The aura around the movie extended far beyond the premiere.

Tony Thibodeau, of the Museum of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff, first saw the dubbed film at Indigenous Comic-Con in 2016.

He, like Wheeler, recognized its potential.

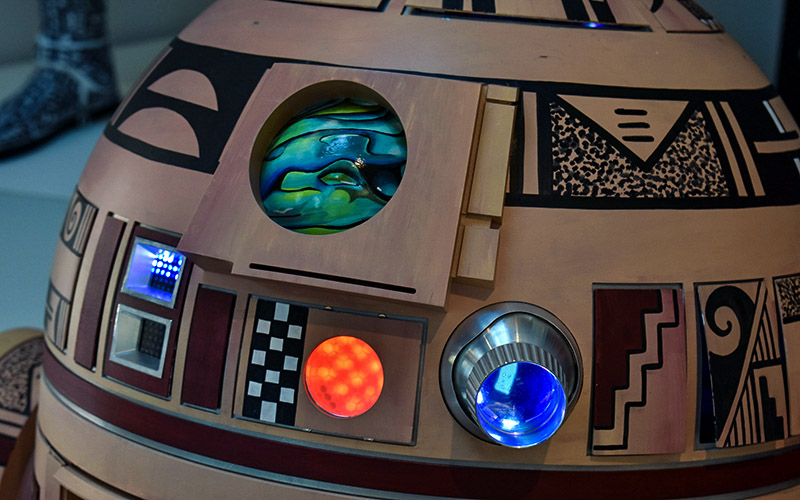

Over the next three years, Thibodeau interviewed Navajo artists inspired by “Star Wars” and curated an exhibition at the museum – “The Force Is With Our People.”

The exhibit, which opened in October 2019, featured works by 24 Native artists that reflect a “Star Wars” influence. The pieces – some of which remain today – included in the gallery included a Hopi R2D2, Hongeva-Camarillo’s golden C-3PO cosplay and an intricately designed Darth Vader helmet.

The sequel: Now on Disney+ streaming, bringing dreams of Navajo actors originating movie roles

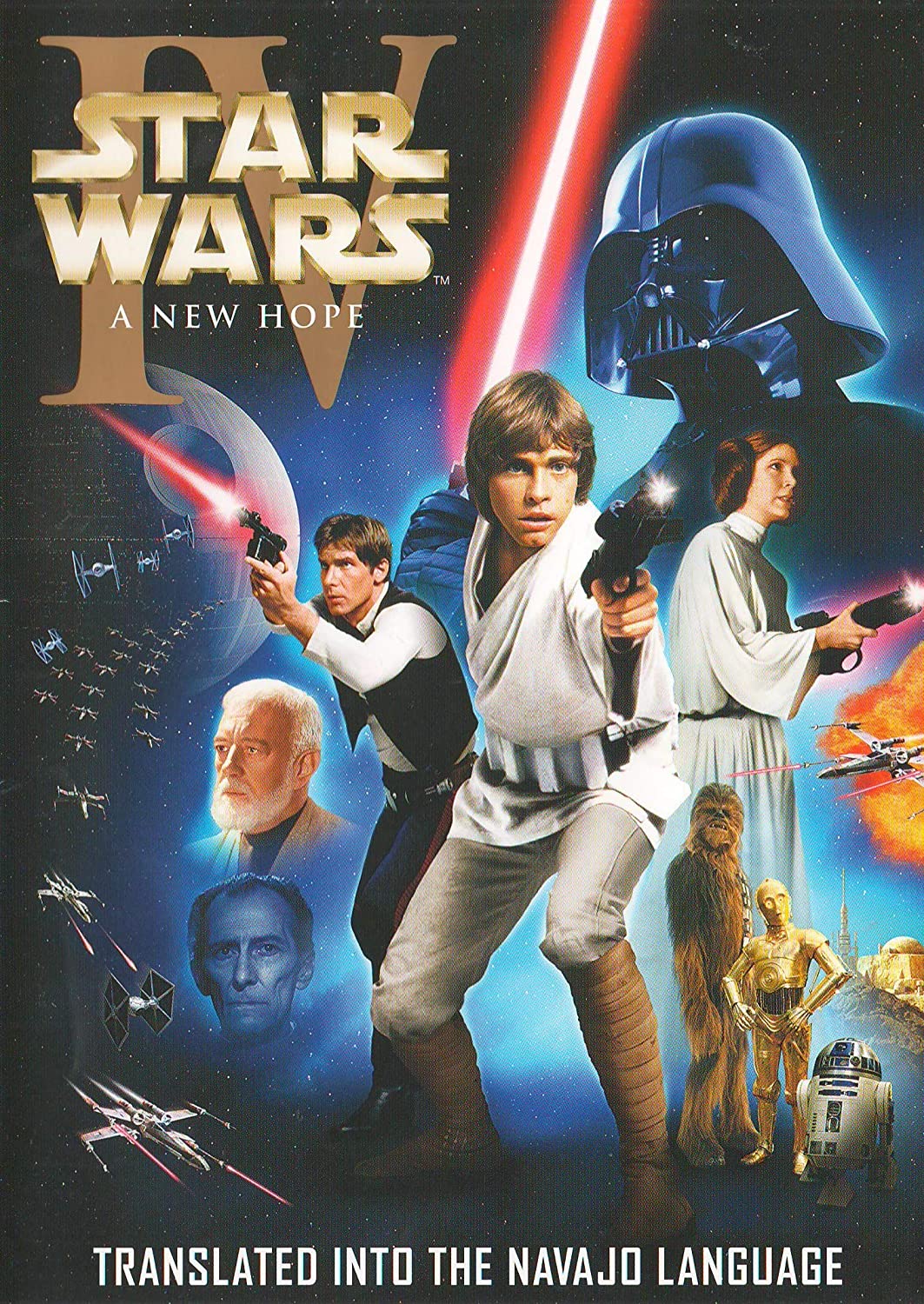

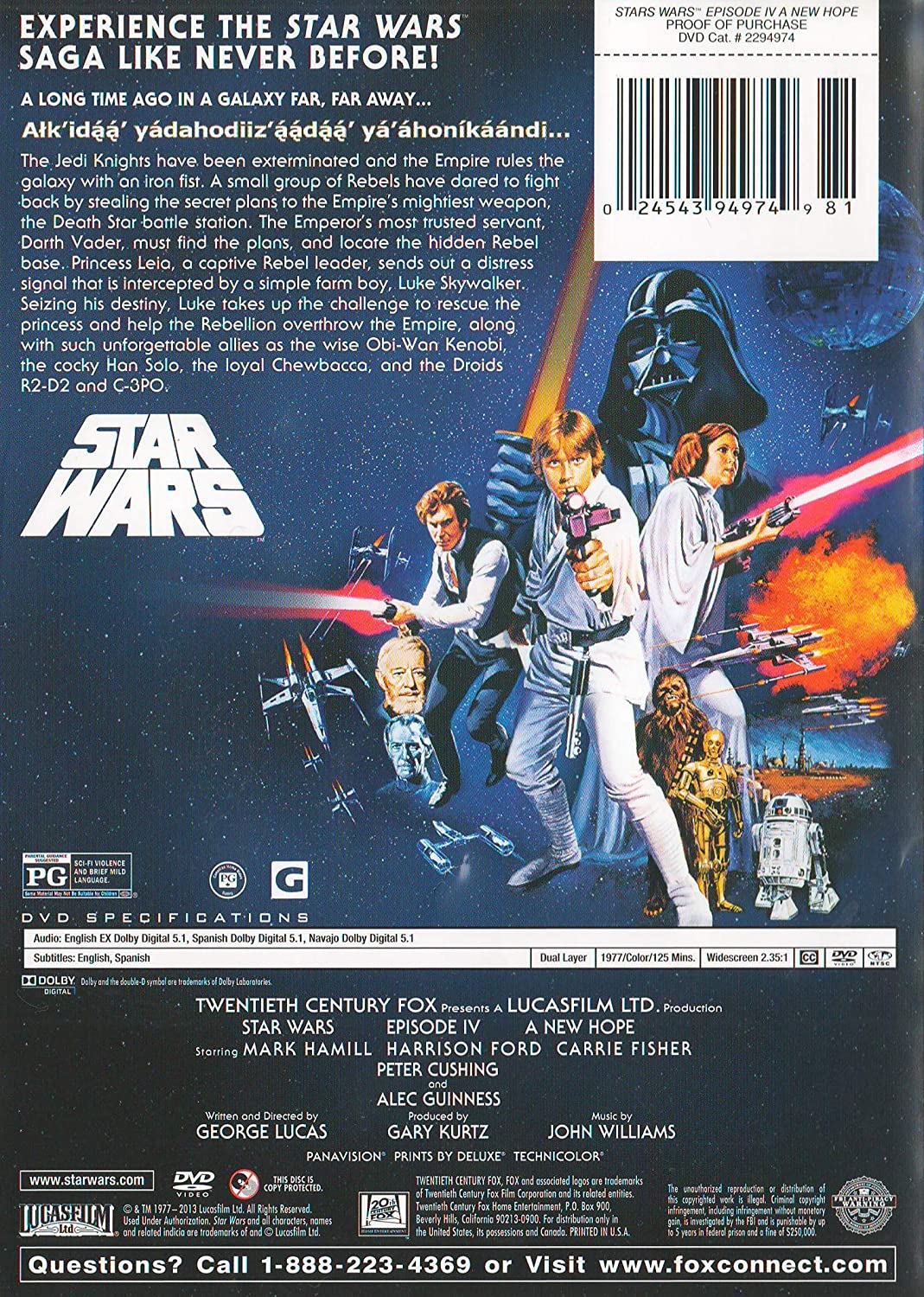

After the 2013 premiere of the dubbed “Star Wars: A New Hope,” Walmarts across the Southwest stocked their shelves with DVDs of the movie. In the years since, it has become more difficult to snag a copy.

Those fortunate enough to have copies used their smartphones to record it from their televisions and uploaded clips to YouTube. Amazon lists them for $100 to $200. Thibodeau borrowed a copy from a Flagstaff library.

The movie now is available on Disney+, the subscriber-based streaming channel, but it takes a bit of an effort to find it. Under the original listing of “Star Wars: A New Hope,” viewers navigate to extras, and scroll to the end to find the translated version.

The film is accessible to most. But for those who live on the far-flung Navajo reservation, which touches four states, internet access is a problem.

“The vast majority of people that live on the reservation don’t have access to quality internet to watch these movies,” Wheeler said. “It being available in a streaming format really benefits our Navajos that are living all over the world.”

Still, the movie engages a new dialogue for Diné Bizaad, and opens doors to conquer other movies.

Note: This story originally appeared on Cronkite News. It is published via a Creative Commons license. Cronkite News is produced by the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University.

Search

Filed Under

Tags

More Headlines

Native America Calling: The ongoing push for MMIP action and awareness

‘Blindsided’: Indian Country takes another hit in government efficiency push

Native America Calling: A new wave of resistance against Trans Native relatives

Urban Indian health leaders attend President Trump’s first address to Congress

‘Mr. Secretary, Why are you silent?’: Interior Department cuts impact Indian Country

Cronkite News: Two Spirit Powwow brings community together for celebration

Native America Calling: Native shows and Native content to watch

VIDEO: Oversight Hearing to Examine Native Communities’ Priorities for the 119th Congress

AUDIO: Oversight Hearing to Examine Native Communities’ Priorities for the 119th Congress

AUDIO: Leaving Indian Children Behind: Reviewing the State of BIE Schools

Cronkite News: Native student program shuts down due to President Trump

NAFOA: 5 Things You Need to Know this Week (March 3, 2025)

Filmmaker Julian Brave NoiseCat makes history at Academy Award ceremony

Senate Committee on Indian Affairs schedules business meeting to consider bills

Chuck Hoskin: Cherokee Nation advocates for Indian Country

More Headlines

‘Blindsided’: Indian Country takes another hit in government efficiency push

Native America Calling: A new wave of resistance against Trans Native relatives

Urban Indian health leaders attend President Trump’s first address to Congress

‘Mr. Secretary, Why are you silent?’: Interior Department cuts impact Indian Country

Cronkite News: Two Spirit Powwow brings community together for celebration

Native America Calling: Native shows and Native content to watch

VIDEO: Oversight Hearing to Examine Native Communities’ Priorities for the 119th Congress

AUDIO: Oversight Hearing to Examine Native Communities’ Priorities for the 119th Congress

AUDIO: Leaving Indian Children Behind: Reviewing the State of BIE Schools

Cronkite News: Native student program shuts down due to President Trump

NAFOA: 5 Things You Need to Know this Week (March 3, 2025)

Filmmaker Julian Brave NoiseCat makes history at Academy Award ceremony

Senate Committee on Indian Affairs schedules business meeting to consider bills

Chuck Hoskin: Cherokee Nation advocates for Indian Country

More Headlines