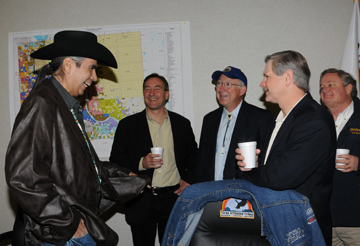

Tex G. Hall, far left, chairman of the Three Affiliated Tribes of North Dakota, discussed oil and gas leasing with, from left to right, U.S. Rep. Rick Berg (R-ND); Interior Secretary Ken Salazar; U.S. Sen. John Hoeven (R-ND), and North Dakota Gov. Jack Dalrymple at the Fort Berthold Reservation on April 3.

PHOTO COURTESY/TAMI A. HEILEMANN, DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR OFFICE OF COMMUNICATIONS

WASHINGTON, D.C. -- Concluding an April 3 meeting with elected tribal and state leaders at the Fort Berthold Reservation, U.S. Department of the Interior Secretary Ken Salazar unveiled accountability measures to aid oil and gas development on public and Indian trust lands in North and South Dakota, Montana and other states across the country. Salazar’s rendition followed his April 2 trip with North Dakota officials to boomtowns and man-camps in the Bakken oilfields, the fastest-growing oil and gas development area in the U.S. It came one week after Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation Tribal Business Council Chairman Tex Hall testified to a U.S. Congress Appropriations subcommittee that the Three Affiliated Tribes need more money and streamlined processes to meet the challenges of the boom at Fort Berthold. “(The) Interior (Department) is committed to expanding safe and responsible oil and gas development on public lands and Indian trust lands,” Salazar said in a prepared statement he framed “as part of President Obama’s all-of-the-above energy strategy.” U.S. President Barack Obama conducted a trip through Western energy-resource states in late March to promote the “all-of-the-above” strategy aimed at supporting every possible kind of domestic power production. Salazar highlighted the implementation of new “automated tracking systems that could reduce the review period for drilling permits by two-thirds and expedite the sale and processing of federal oil and gas leases.” It responded to Hall’s earlier request for a “permanent one-stop shop” permitting process to simplify paperwork. With Bureau of Indian Affairs supervision and lease management, the Three Affiliated Tribes have encouraged oil production, generating massive increases in royalties for the tribal government and individual landowners. Royalties from individual allotments on Indian trust lands in 2008 totaled $1.8 million, and rose to $106.7 million in 2011. In the first three months of 2012, royalties totaling nearly $60 million were collected, Salazar said. The increases came after Salazar dissolved the Minerals Management Service and delegated its responsibilities to three separate branches of the new Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation and Enforcement. The reorganization was largely in response to charges of industry-government collusion, the BP Deepwater Horizon drilling rig disaster in 2010, and an effort by allotment owners nationwide to reap overdue, concealed benefits from oil and gas leasing. Compared to the last three years of the previous administration, receipts are up due to a 13-percent increase in domestic oil production during the first three years of the Obama administration, according to Salazar. The volume of drilling applications in the Bakken shale formation has ballooned 500 percent during the past five years, half of it on American Indian mineral estates, Salazar noted. Since 2007, applications to drill on Fort Berthold, in the heart of the Bakken, have gone from 0 to 175. More than $3 million in drilling permit fees were collected there in fiscal 2011, Salazar said in the prepared statement. Inspections by the Interior’s Bureau of Land Management also continue to rise. In fiscal year 2007 the bureau conducted four inspections on Indian minerals; in fiscal year 2011, a total of 429 inspections were conducted. For the same time frame, for non-Indian federal minerals, inspections rose from 200 to 718. As the lead agency for permitting, inspection and enforcement activities for both federal and tribal resources, the BLM is responsible for ensuring measures to maintain environmental quality and human safety. The impact of the oil boom has prompted Hall to prod Congress for housing to support a new health facility; funding to address the severe damage that oil and gas development has caused to roads; continued funding for permanent “one-stop shop” permits like that provided in fiscal year 2012; additional BIA and BLM personnel to process the oil and gas permits for tribes, and legislative postponement of federal funds to implement the BLM’s newly proposed regulations on hydraulic fracturing. “While the oil and gas boom on the reservation and in the region has brought with it many positive things, it has also brought us some serious problems,” Hall testified on March 27 in Washington, D.C. “One of those problems is a total lack of available housing within 100 miles of our reservation,” he told the House Appropriations Subcommittee on Interior, Environment and Related Agencies. Hall said the tribe needs affordable housing, especially in order to provide for staff to open its new health clinic. “Since the boom, every available housing unit within 100 miles of our new clinic has already been placed under contract or lease," Hall said. "Even when housing does open up, which is extremely rare, two- and three-bedroom homes are now renting for in excess of $2,500 per month.” “The bottom line is that we need a minimum of $12 million to construct homes for the 60-plus (Indian Health Service)-funded employees that this committee has appropriated dollars to hire,” he said. “The MHA Nation has already done its part by spending in excess of $1.6 million in tribal funds to prepare the site for these new homes and bringing in the utilities, but we simply cannot afford to construct those units.” Hall showed lawmakers pictures of “the road safety crisis that oil and gas development has created” on the 1-million-acre reservation. More than 260 miles of the 1,081 miles of road on the reservation are tribal or BIA. And just a little over 25 percent of all the reservation’s roads are paved. “None of these roads were built to handle the types of heavy equipment and heavy trucks utilized by the oil and gas industry,” said Hall. “Those roads have been almost totally destroyed by oil- and gas-related traffic.” “I fear every day that I will get a call telling me that a school bus full of children has tipped over killing a number of our students,” he said. “I already receive almost daily calls telling me of serious accidents involving our members. In fact, we now have so many accidents on my reservation that my staff does not even bother to call me unless the injuries are life-threatening. The situation has now gotten to be that bad.” “If the federal government truly wants to see oil and gas development within the boundaries of the United States, it has to take responsibility for the damage that this type of production causes to its own federal roads and small communities like MHA,” Hall said. (Contact Talli Nauman at talli.nauman@gmail.com)

Join the Conversation