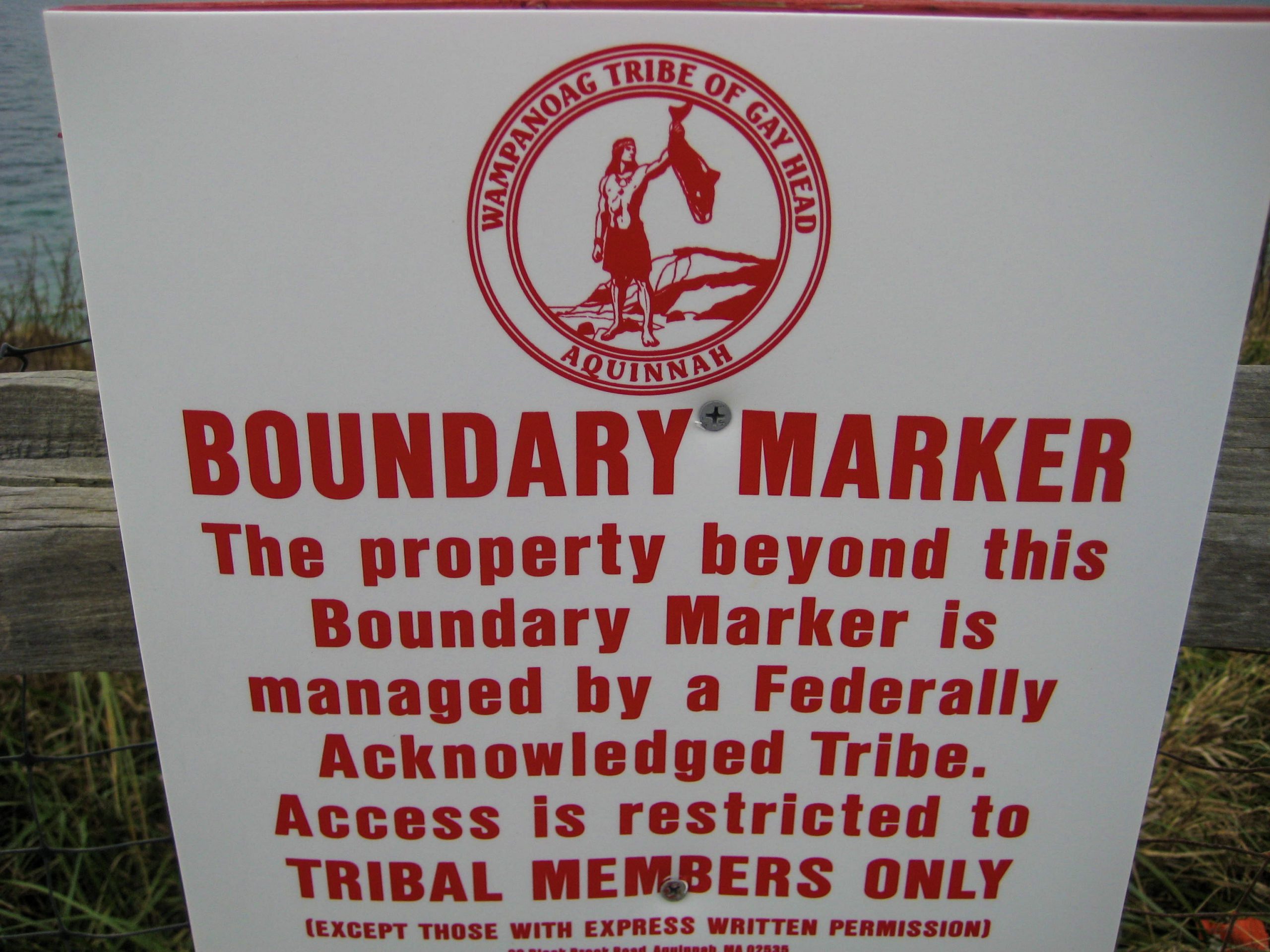

A boundary marker in Aquinnah, Massachusetts, home of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head. Photo: John Pittman

The following is a May 7, 2021, blog post shared by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA.

Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah)

Aquinnah (originally known as Aquinnah, and then formerly known as Gay Head): The shore lands under the hill at the end of the island (general translation)

Wampanoag: People of the First Light

In early 2020, when COVID-19 shook the world and became part of the collective vocabulary, the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) knew what they had to do. With their inherent resilience, ingenuity, and compassion, all moved quickly to keep members of the Tribe safe, healthy, and protected.

For this was not the first pandemic the Tribe has weathered.

In 1616, before the Pilgrims’ arrival, a still-mysterious disease caused an epidemic which decimated an estimated 75% of the population of the 69 villages that made up the Wampanoag Nation. With that history, Tribal Council Chairwoman Cheryl Andrews-Maltais immediately called for a shut down in their community.

With the urging of the Chairwoman, the Tribal Council approved a Resolution declaring an immediate “State of Emergency and Major Disaster” under the Robert T. Stafford Act. Additionally, the Tribal Council determined that as a long-standing Self-Governance Tribe, the Tribe is capable of managing themselves, and as such, should be a direct recipient of federal assistance through the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Public Assistance program.

That was just the beginning of the issues they faced as there was great concern about being isolated and on their own. The unknowns seemed overwhelming. How to notify all Tribal Members? How to determine the COVID-19 needs of the Tribal Members? How to provide PPE to all as well as durable medical goods to Tribal Members due to early releases from hospitals? How to test Tribal Members and assist those who test positive? How to perform contact tracing to avoid or mitigate the spread of the virus? How to house Tribal Members or their families who may have contracted or have been exposed to the virus? How to ensure that Tribal Members returned to their homes free from the virus to avoid the spread of or reinfections? How to finance a shut down and keep staff employed? How to create a telework structure while assuring connectivity for telework, telehealth, remote educational purposes, and other needs, when there is limited computer access and limited internet bandwidth?

These were just the primary concerns.

“Beyond our small size in Gay Head/Aquinnah, we are an isolated community with limited resources,” said Andrews-Maltais, explaining that their island population is only around 300 members. “Our location on the southwest tip of Martha’s Vineyard, an actual island, presents numerous challenges.”

Between the financial need and logistical challenges that they face as an island Tribal Nation, their unique isolation was difficult enough; add to that the need for an ongoing source of PPE as well as cleaning and sanitizing supplies and imparting the gravity of an urgent situation. Clearly, help was needed.

Serving in her 4th term, Chairwoman Andrews-Maltais is no stranger to knowing what her Tribal Community needs are and what their human resource capacity was. She realized early on that it was simply too much to address and too big to handle all on their own.

FCO/Tribal Liaison Adam Burpee from FEMA was assigned to the task once the Tribe determined they wanted to be a direct recipient for FEMA support. The support provided by Liaison Burpee was sometimes in-person, and on-site, such as PPE delivery. Additionally, to assist them through the required activities and documentation needed to become a recipient, a first for the Tribe, Burpee provided some necessary and welcomed support. Additionally, Burpee assisted with resource requests for PPE, emergency food needs, and guidance regarding non-congregate sheltering needs.

“The biggest immediate challenge for this Tribe was their staffing shortfall – without a dedicated Emergency Management department, they had their Tribal Chairwoman juggling executive leadership of the Tribe, mundane administrative actions for the Tribal Nation, press, and in-depth tactical activities associated with response to an unprecedented disaster,” explains Burpee. “This event stretched the Tribe to the absolute limit.”

Andrews-Maltais, according to Burpee, has a strong team and a Natural Resources department that has been more than adequate in ordinary, and even extraordinary disaster operations. “This was so much more,” said Burpee. “Building capacity was at the heart of the challenge for this Tribe; I can tell you having worked with a few dozen other Tribes in the intervening months, that building capacity is a huge challenge across the U.S. Tribal governments don’t have a good mechanism for self-funding; The Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) doesn’t levy taxes, they don’t have a revenue stream from gaming, and their Tribal Citizens are already taxed by federal, state, and local governments. Located on Martha’s Vineyard, they face the additional challenge of a housing market that swings far to the side of unaffordability during the tourist season. As a result, there is either an exodus of Tribal talent and support during the summer, or worse – housing instability that results in Tribal Member Citizens ‘couch surfing’ with relatives or friends when their living arrangements become unaffordable. This is a worst-case scenario for pandemic conditions.”

The Federal Government, the State and the Tribe all had shut down and shelter in place orders issued. There were many who were concerned about the multigenerational housing, and the need to isolate and quarantine until more was known about the disease; especially the Elders who were a bit frightened and nervous about being without access to friends and family. “They were of particular concern to me as so much of their days were spent gathering with others, and socializing in our community center,” according to Andrews-Maltais. “To protect the health and safety of our Tribal community, every public or common area had to be closed, from our offices to the schools. We couldn’t travel nor could we have visitors. The stakes were too high to risk exposure to this unknown virus, when it specifically attacked the Elder population, who are precious to us, as well as people who have underlying health conditions, which the majority of our People have.”

Once the shut-down was in place, all common areas were disinfected, and proper protocols were developed and followed, cleaning and sanitizing with the limited supplies on hand. It was imperative to follow the “new” best practices to stay safe and healthy. “We worked with our federal partners from Health and Human Services (HHS), to the Center for Disease Control (CDC) to the Indian Health Services (IHS) and FEMA, to determine what the best path for our Tribe would be, to avoid, prepare for and mitigate the effects of the COVID-19 virus”

The Chairwoman created an entire COVID-19 Emergency Response Services Team (ERST) out of thin air. “We needed to do so much, and we simply didn’t have the staff to perform all the work or execute the missions that we set out to accomplish. We needed to be as inclusive as possible to address these emergency needs of all our Tribal Members, far beyond the confines of the island, since only 25% of our population resides on Martha’s Vineyard. So, we contracted Tribal Members to be our ERST. This not only provided desperately needed work, since most people were out of work due to the pandemic. It also created a sense of familiarity, comfort and connectivity for our Tribal Members, especially our Elders so they didn’t feel so isolated”. This was all new. “The ERST became that friendly and reassuring connection and voice, providing helpful information and access to services, PPE supplies and nutritional food supplements”.

Regina Marotto from FEMA was also serving as a Tribal Liaison at that time. “FEMA provided a lot of PPE; masks, respirators, face shields, gowns, and medical supplies thermometers, alcohol pads, ice packs along with emergency food boxes, and hand sanitizer,” notes Marotto. “We shared information from our USDA partners, enabling the Tribe to participate in the Farmers to Families program. They received food deliveries to support their community and local partners in need, even sharing excess food with other Tribes in the region. Through FEMA’s Voluntary Agency Liaison, we have also been able to meet additional needs such as durable medical equipment, masks, and other goods.”

“Many Tribal Nations remain wary of the federal government – rightly so due to the atrocious history, policies, and eras – however, we have been successful in growing our relationships with the Tribes in New England throughout the COVID emergency. It has helped that our team has stayed mostly the same, rather than rotating different people in and out. In my experience working in Indian Country, having the same, consistent, effective point of contact often leads to trust and continued relationship building.”

That is echoed by Chairwoman Andrews-Maltais. “Knowing that FEMA is there with supplies, support and manpower is heartening. We feel secure and comfortable in our federal partnership. As Tribal Leaders, we are often faced with the reality that as soon as we build a relationship with individuals as part of our federal partnership, they are rotated out to another detail. This leaves us starting to build a new relationship all over again, which doesn’t support the purpose and intent of the federal Trust and Treaty obligation the United States has to the Tribes.”

Burpee says the Tribe was willing and eager to help their own. “This Tribe is a close-knit community and were brought closer together through this hardship. I can’t count the number of times on a call some unmet need we had identified was countered with, “I have a relative who could do…” fill in the blank. Key to building trust was looking for ways to build on existing common ground and finding ways to make personal connections across the (literal) divide. I made a few trips to Martha’s Vineyard to that end and it paid great dividends while helping me to understand some of the specific challenges the Tribe faced.”

Chairwoman Andrews-Maltais needed to facilitate a new way of living-for now. “I use the analogy of a Swiss watch, with so many intricate moving parts that need to run in perfect sync. The situation was truly that complex.”

While the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) had faced and overcome adversity on their own in the past, this situation required outside resources. FEMA was there. “What we offered was an opportunity for them to seek reimbursement for the immediate needs the Chairwoman and her staff identified to protect Tribal Member Citizens and safeguard her people,” notes Burpee. “The limiting factor in almost all her decisions was not lack of ability or lack of access – but uncertainty about funding. The Tribe has a great network throughout southeast Massachusetts, and even into the surrounding states, including northern Long Island with other Tribes, state and local jurisdictions, and with volunteer agency partners.

That was used to their advantage.

“Expanding our footprint to include off-island or mainland Tribal Members allowed us to manage this pandemic as greater numbers meant greater resources. Every possible local and federal agency-from the Indian Health Service to the Salvation Army to FEMA – stepped up to help with funding or people or goods and services. We were greatly concerned about testing for COVID; after some collaborative discussions, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health provided that opportunity,” adds Andrews-Maltais. “They were great to work with. We even created our own forms so our tests and results would be easily identifiable and attributable to Indian Country, so more accurate data could be collected.”

“When there has been an identified need among multiple Tribes in the region, we’ve made every attempt to combine efforts to meet the needs of all Tribes. Example: in April 2020, three Tribes needed emergency feeding but none were going to meet the minimum quantity needed to order through direct federal assistance,” explains Marotto. “The Tribes worked together amongst themselves and with FEMA. We combined the need from all and were able to order through the process this way, ultimately meeting the emergency need.”

Such partnerships succeeded in moving the Tribe towards a new normal while keeping the number of COVID cases relatively low. “All Tribes in the region have fared much better than their respective states and surrounding communities due to the early action they took, and policies implemented,” according to Marotto.

“Once we had our capacity identified, we reached out to the other Tribes in the area and shared the resources we were able to secure. For us as Tribal Nations, we are all related and we feel particularly close to each other during times of stress and struggle. So, I couldn’t have been happier to be able to help our other Tribal Brothers and Sisters,” says Andrews-Maltais. “Our wonderful ERST coordinated with the other Tribes’ people and we either met them half-way or delivered food directly to their locations. The extraordinary efforts of our ERST cannot be praised enough. Whatever it took to get the job done is what they did. They are the backbone of the entire initiative and operation. Without their dedication and commitment to our/their People, we could have never been as successful as we have been. They have distributed or delivered thousands of meals and PPE, and have vaccinated hundreds of our Tribal Community Members, all with a smile, despite the fact that they were placing themselves in harm’s way, just so our Tribal Members were taken care of.”

Though the crisis phase of the pandemic has passed, Andrews-Maltais stresses the collaboration remains ongoing.

“We were so fortunate to have such great partnerships with our FEMA Reps. The information regarding access to necessities that the Regional Administrator and Liaisons provided, helped us develop a sophisticated delivery mechanism. We utilized our logistical knowledge and ability to rent refrigerator trucks to get food products delivered and distributed to both the island and mainland locations, including deliveries to our eldest Elders who we encouraged to stay at home. We distributed and delivered thousands of pieces of PPE to all Tribal Members regardless of where they resided. We continue to provide food, PPE, durable goods, electronics and general welfare support to our Tribal Members as long as we can reach them.” The Chairwoman added, “We’ve also cultivated relationships with the State Police in Massachusetts and Rhode Island, VFWs, American Legions, and other charitable organizations to use their locations for conducting vaccination clinics to inoculate all Members of our Tribal Households and Tribal Community Members. At this point, we have it down to a science.”

FEMA representatives continue to support the Tribe. They check in with the Aquinnah at weekly one-on-one coordination calls, more often as needed or requested. Monthly meetings are held with all Tribes in the region to provide updates, share information, and have a direct conversation with FEMA and the Assistant Secretary for Preparation and Response (ASPR) offices’ regional leadership.

To date, the Tribe has not yet requested advance or direct federal support for their vaccine programs due to the necessity of getting the vaccination needs met first. FEMA continues to assess any potential need for PPE, vaccines, or other COVID-related activities. “We are proactive in providing information on process, policy, and availability,” says Marotto, who maintains a close connection to the Aquinnah as FEMA’s Tribal Liaison Officer. “Recently, as our regional warehouse prepared to close, we coordinated with all direct-recipient Tribes to match available resources to any potential need. Deliveries of PPE and other material were completed as requested. Throughout the pandemic, we’ve consistently received positive feedback from the Tribes we serve and have adjusted when opportunities for improvement have presented.”

As with the rest of the country, the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) is gradually reopening, with vaccines being administered for those 16 years old and above. “When the approval comes to expand that age group to 12-15, the Tribe will circle back to the families to make sure everyone who wishes to be vaccinated is,” the Chairwoman added. “However, due to the variants and continued concerns of the effectiveness of the Emergency Use Approval of the vaccines on these emerging variants, most work remains in a virtual state with a slow and cautious return to in-person work”.

The Tribe’s sense of community, coupled with their keen knowledge and fierce implementation of emergency management protocols, have kept them relatively healthy and intact, despite suffering Tribal Member losses due to the virus “Yes, we have suffered losses of our People, and we will never know the full extent to which we were all exposed; and who had the virus and when. From our symptomatic experiences of how we felt, and the knowledge that early on, people were infected, and carrying and spreading the disease, whether mildly symptomatic or asymptomatically, the long-term effects are still yet to be determined. We did our best, and we will continue to try to stop the spread and keep our Tribal Community as safe as possible. As the Leader of my Tribe, it’s incumbent upon me to do whatever it takes to ensure that my People and my Community is as safe as humanly possible. So, we will continue to work with FEMA and our other federal partners to do just that.”

The literal translation of their name has perhaps never seemed more fitting. For “the people of the first light” at the shore under the hill at the end of the island the Aquinnah Wampanoag continue to shine brightly as a beacon of hope, strength, and resiliency.

“To be Wampanoag is inside you. It’s really something that you can be proud of.”

–a Tribal Member